After Katrina, a priceless musical archive was thought lost. It showed up in Torrance

Hurricane Katrina pushed into New Orleans early in the morning of Aug. 29, 2005, and within a few hours, the first floodwaters had crossed the doorway of Sea-Saint Studio. One by one, the three outfall canals bordering Lake Ponchartrain failed and water rushed into Gentilly, the quiet residential neighborhood where Allen Toussaint’s home and studio were located. Even as the storm moved out, the lake continued to pour itself into the city. The next day, Aug. 30, skies were blue and Sea-Saint was fully submerged.

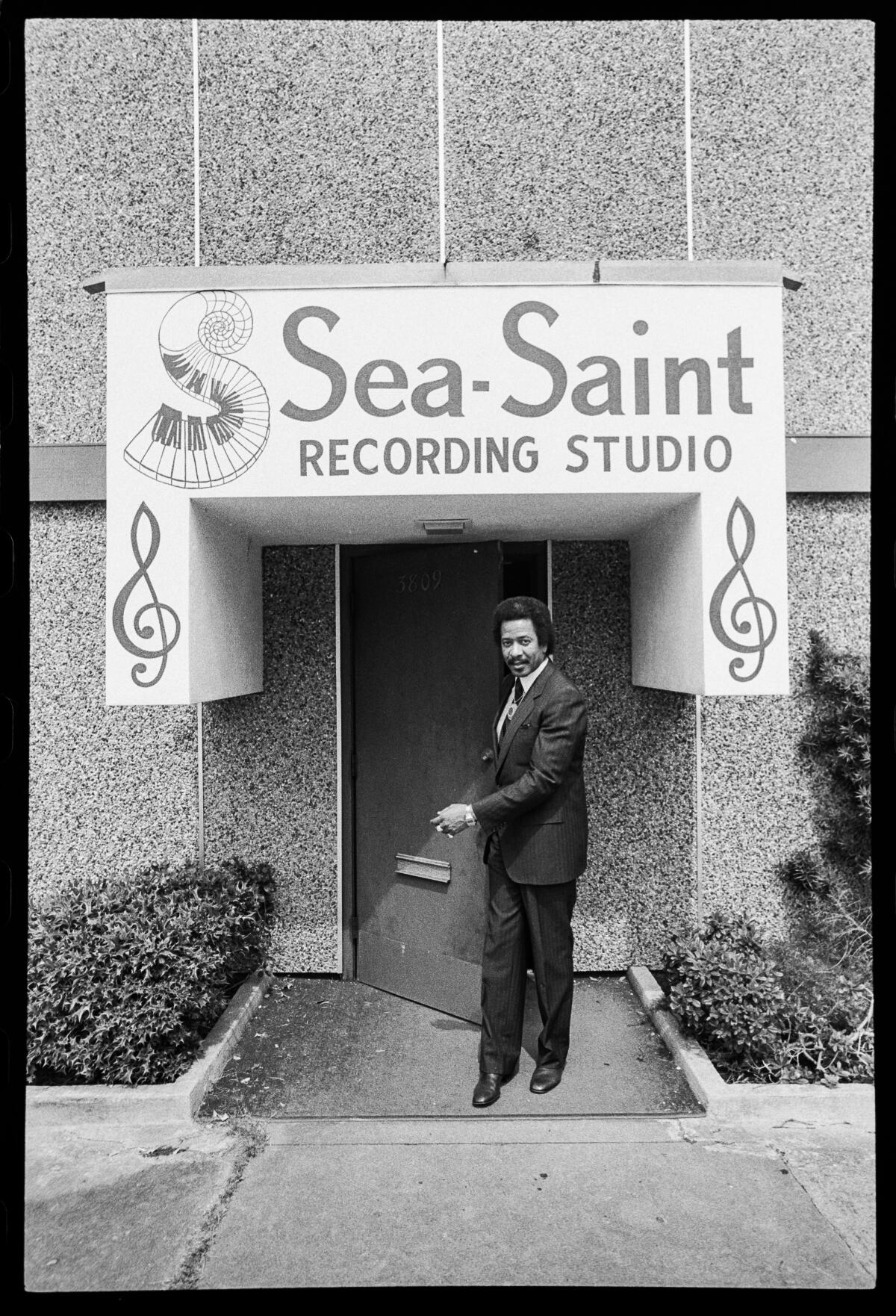

Since 1973, the converted paint and lumber outlet had been home base for Toussaint, whose collaborations with local talent gave the city a fresh signature in the ‘60s and ‘70s and elevated the former session pianist and songwriter into the eminent maestro of New Orleans funk and soul. Sea-Saint brought us the original recording of “Lady Marmalade” by the proto-feminist R&B trio LaBelle. It served as a clubhouse for Rock and Roll Hall of Fame nominees the Meters and the late Dr. John in their heyday. It was where an infinite cast of musicians and artists were transformed by Toussaint’s ingenuity. Homegrown talent was given access to the same lavish musical imagination that Toussaint extended to Paul McCartney and Paul Simon, who flew halfway around the world to get the local feel of that room.

Toussaint evacuated to Baton Rouge, and then to New York City, where he settled into a well-appointed apartment for the next several years. His Gentilly residence was eventually demolished; Sea-Saint was left abandoned. Toussaint’s business partner and co-owner Marshall Sehorn passed away in 2006. In a 2007 interview with Larry Appelbaum, senior music reference librarian at the Library of Congress, Toussaint was asked what became of all the master tapes in the studio. “They got wiped out,” said Toussaint in his inimitably gentle way. “Some of my own personal masters were saved — but of course there was a whole lot more in there.”

‘An amazing discovery’

Located on the border of Torrance and Gardena, the Roadium Open-Air Market is open from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m., 363 days a year. A lifelong resident of Gardena, Mike Nishita, 56, has been coming here since he was a kid, when slasher movies were still beamed onto the big drive-in screen at night. In the 1980s, he bought rap records from Steve Yano, whose booth was the first outlet for Dr. Dre’s mixtapes. Beginning in 1991, Nishita was employed as the in-house DJ for Quincy Jones Productions, warming up crowds before tapings of “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air” and “Mad TV.” He quit Hollywood in 2003 because he was having more fun buying storage auctions and canvassing swap meets. The farther out he went, the better his finds became. He worked the outlying circuit, from Golden West College in Huntington Beach to the Pico Rivera Indoor Swap Meet — but he always returned to the Roadium, which is 10 minutes from his house.

If you default on a storage unit in Los Angeles County, chances are strong that your belongings will surface beneath one of the tented stalls spread across the parking lot on Redondo Beach Boulevard. Celebrity status means nothing to the California Self-Service Storage Facility Act, which permits the lien sale of a storage unit to take place within two months of a missed payment. Over the years, Nishita has come across valuables from the foreclosed units of Waylon Jennings, ‘80s hardcore band Suicidal Tendencies, and the Motown songwriters Lamont Dozier and Eddie Holland. Once a unit is auctioned, the purchaser has no legal obligation to the previous owner of the property — even if that owner is Suge Knight, whose clothes, shoes, photos and Death Row Records awards passed through the Roadium about 10 years ago.

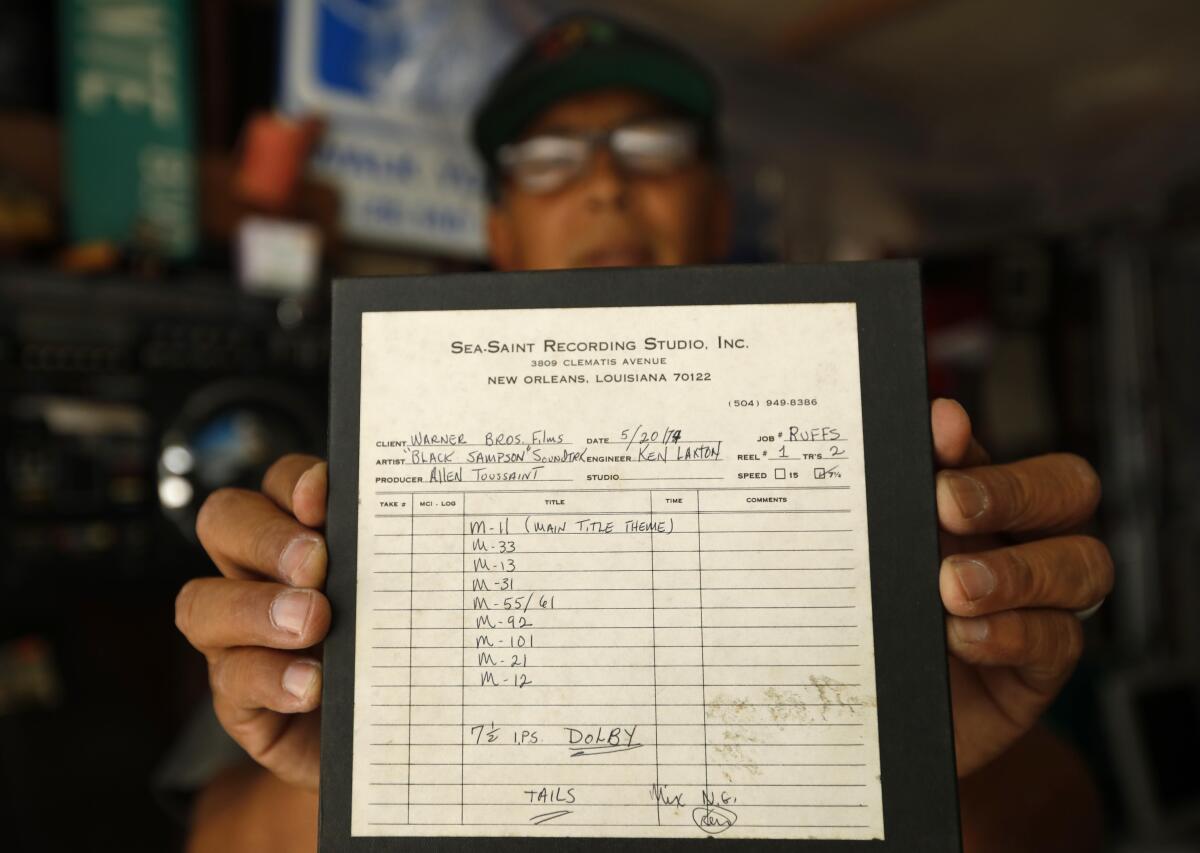

With other committed Roadium pickers, Nishita parks before dawn on Monday mornings to rush sellers as soon as they start unloading the weekend’s storage buys. One Monday in January 2018, the usual crowd was thinned by a light drizzle. The Roadium vendors call Nishita “Hawaiian Mike.” He was signaled over to look at 16 boxes of tapes a vendor had just purchased at auction from a foreclosed unit in Hollywood. “You figure VHS, cassettes, who knows what,” says Nishita. He recognized some of the names written on the 7-inch-by-7-inch boxes — the Meters, Lee Dorsey, Dr. John — but assumed they were homemade copies of old albums. Prior to the widespread availability of cassettes in the 1980s, reel-to-reel tape was used as an early form of home duplication. Then he noticed the official label affixed to some of the boxes:

Sea-Saint Recording Studio, Inc.

3809 Clematis Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana, 70122

The vendor was asking $100 per box. Nishita bought all 16. On the way home, he called Mario Caldato, his best friend since their days in machine-shop class at Gardena High School in the late 1970s. They played in bands and ran a mobile DJ unit in the 1980s before Caldato met the Beastie Boys and became their in-house engineer and co-producer from 1988 to 1998. Mike’s brother, “Money Mark” Nishita, became the Beasties’ keyboardist.

All three of them convened in Gardena, where the contents of the boxes were laid out in Mike’s garage. “It was mind-boggling,” says Caldato. Seventy-five percent of the boxes were quarter-inch tapes, the high-quality but portable format that professionals used to share and test recordings prior to the 1980s. Musicians would record their parts in the studio onto a two-inch, multi-track tape machine, then create a mix onto a quarter-inch or half-inch tape that could easily be played by anyone with a reel-to-reel. “Those are the tapes you hope to find because the mix is already preserved as the musicians intended you to hear it,” says Caldato. “This is what Toussaint and the artists actually took home to listen to after they cut a track.”

Like tens of thousands of others driven from their New Orleans homes a decade ago, musician Allen Toussaint had to abandon his beloved hometown in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

When a finalized master tape was shipped off to a record label or pressing plant, Sea-Saint would often keep a “safety” copy of the master on quarter-inch tape. In the event that masters are lost, discarded or decayed — an inevitable fate for the majority of American music recorded prior to the 1980s — quarter-inch copies from the studio of origin are the closest one can get to the source. For many of these recordings, the quarter-inch tapes are all that remain.

Piled in Nishita’s garage were multiple reels by the Meters, including quarter-inch master copies of their eponymous 1969 debut and their 1974 album “Rejuvenation” — two of funk’s most formative works, both frequently sampled by hip-hop producers — along with unreleased tracks and jams. There were reels of Toussaint, Dr. John and every big-timer in New Orleans R&B: Irma Thomas, Lee Dorsey, Huey “Piano” Smith. There were reels with names prized by soul and funk collectors: Betty Harris, Willie West, Eldridge Holmes. And still dozens more containing demos or one-off recordings marked by unknown names: Laura Jacobs, Carla Baker, “Eugene.”

Among the stacks was a demo recorded by Meters guitarist Leo Nocentelli, dated 7/1/75. Ten songs, just voice and guitar. It sounds like Jimi Hendrix doing “(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay” alone in a hotel room. The world doesn’t know it exists, let alone that it’s residing in a garage in southwestern Los Angeles.

“Those are tapes I thought were destroyed or put somewhere where they’d never be found,” says Nocentelli, 73, speaking from his home in New Orleans. “What you’re telling me is an amazing discovery.” He expressed shock, confusion, delight and more than a little anger. When asked how tapes of such significance could get misplaced, he said: “You have to understand. This is a business of brutality.”

Most of the tapes were stamped with the names of Marshall Sehorn or Allen Toussaint, and several were dated and notated in Toussaint’s elegant cursive script. A smattering of boxes came from studios in other locations: Nashville, Muscle Shoals, Los Angeles. There were a handful of tapes from Cosimo Matassa’s studio, the hub for New Orleans R&B prior to Sea-Saint. A number of boxes containing folk and rock acts seemed to come from another location entirely, but the majority of the tapes came from Sea-Saint or Cosimo between 1968 and 1979. 673 reels total. Possibly 3,000 hours of music. The common thread was Allen Toussaint.

“I was looking at the names, trying to make sense of it,” says Caldato, who currently operates his own studio in Eagle Rock. “Sea-Saint and Cosimo, those are the mecca for New Orleans. How could this be? How could someone lose track of this or let it go?”

‘There’s no “Lady Marmalade”’

“Let me ask you something,” says Bill Valenziano over the phone, in a thick but amiable Chicago accent. “Is this really newsworthy?”

Now 80, Valenziano lives in Ventura County and has been active in the music business since the 1960s. He worked in marketing for Capitol, Island and Arista, before starting his own company that acquired and licensed music previously owned by other labels. “I have a small catalog of what I purchased over the years from 1980 to 2005,” says Valenziano. “Mostly Gulf Coast music. I have some valuable rights, which I maintain and use for licensing purposes. And I have a lot of not-so-valuable rights.”

Valenziano says he purchased Sea-Saint from Toussaint and Sehorn in 1995, when the studio’s business had slowed and Toussaint and Sehorn were beginning to dissolve their partnership. After the Katrina floodwaters receded, Valenziano sent Roger Branch — an engineer who helped manage the studio — to retrieve tapes from the building. “A lot of them weren’t in great shape to begin with and then they were living underwater for a while,” says Branch, who hauled thousands of soaked and corroded tapes to a dumpster. He estimates that less than 25% of Sea-Saint’s total tape archive was salvaged. Most of what was recovered came from the second story, in a room adjacent to Toussaint’s office, which stayed dry during the flood.

Valenziano moved the surviving tapes to California, where he put them into storage. A portion of those tapes were relocated by an unnamed third party to a second storage facility. That unit foreclosed; the Roadium vendor won the unit at auction; a few days later, Nishita bought them directly off the vendor’s truck.

The tapes Nishita purchased represent only a portion of Sea-Saint’s last remains. The rest are still in Bill Valenziano’s storage unit in Ventura County, where he has tired of paying to store tapes he says number “in the low thousands.”

“There are no more fabulous recordings by Paul McCartney,” says Valenziano. “There’s no ‘Lady Marmalade.’ I had checked in my head that 2020 would be the year that I deal with this. And if I can’t find a new owner ... do you have time to have a bonfire at the beach?”

‘Like my dad said, “It’s only stuff” ’

“These are some of the founding documents of New Orleans funk,” says Keith Spera, a veteran New Orleans journalist who writes for the Times-Picayune and the New Orleans Advocate. “These tapes were part of that incredibly rich creative period that laid the groundwork for a lot of New Orleans music that followed, and by extension, impacted decades of popular music to come.”

Matt Sullivan (Light in the Attic Records) and Eothen “Egon” Alapatt (Now Again Records) were two of the early visitors to Mike’s garage. Both specialize in re-releasing rare and overlooked music from the past, and both expressed interest in partnering to archive and release the music. Both also acknowledged that the legalities surrounding the tapes were prohibitive.

Every song in the collection represents a jigsaw puzzle with pieces owned by separate entities. A label might own the sound recording rights, while an individual owns the publishing rights, and a third party owns the actual tape on which the song was recorded. Sullivan says an upcoming Light In the Attic compilation covering soul music from Memphis between 1977 and 1987 has already taken nine years and counting. “The biggest travesty,” says Alapatt, “would be if the Toussaint tapes get locked up in litigation and no one ever gets to hear the music.”

Earlier this month, a five-song reel-to-reel tape by an obscure soul group called the Decisions sold on Ebay for $1800, not including rights to the music. Alapatt estimates an original Meters reel on its own might sell to a collector for $10,000 to $15,000. As much as a specific tape might be of interest to various parties, the value of the Sea-Saint tapes becomes more singular when taken as a whole; the tapes encompass a cross section of activity inside a great American musical culture during one of its golden periods.

Clarence “Reginald” Toussaint — who served as an in-house engineer at Sea-Saint and currently oversees his father’s estate alongside his sister, Alison Toussaint-Lebeaux — says he would like to see the tapes returned to each individual performer. “Those musicians are the only people who can do anything with the music,” he says. “Without them, all you have is a tape to play in your house.”

Sea-Saint may represent the single biggest loss of cultural artifacts during Katrina, but that loss was widely unreported, in part because Allen Toussaint didn’t raise a fuss over the tapes. “Like my dad said, ‘It’s only stuff,’” says Reginald, 57. “Some people lost so much more than us because people lost lives.” Tapes were just tapes. To Allen, that was the beauty of music — as long as you were breathing, you could always get up tomorrow and make more.

In the years following the flood, Toussaint experienced a career renaissance. He liked to say that he “lived and worked in New Orleans until a booking agent named Katrina put me on the road.” After decades in which he spent almost every day inside Sea-Saint, he began touring extensively for the first time and released three solo albums, including a full-length collaboration with Elvis Costello. He died on Nov. 10, 2015, the night after performing a concert in Madrid.

Both Sullivan and Alapatt would like to see the collection go to an institution that will properly store, archive and make the material accessible to the public while also leaving open the possibility for partnerships to commercially release specific works. Before an institution steps in, the tapes would have to be properly cataloged and appraised — a delicate and time-consuming process that Nishita can’t afford to undertake alone.

Last year, Nishita was contacted about the possibility of selling the entire collection to a producer/engineer who works for one of the world’s most successful rappers. From their perspective, the archive is an untapped mine of exclusive drum sounds and samples from one of the greatest funk producers of all time. (Toussaint has a claim to being one of the most sampled musicians in the history of hip-hop, second only, perhaps, to James Brown.) The number that was floated was $250,000, but Nishita let it pass. From the beginning, his intention has been to resell the collection as a whole to an entity with an interest in letting it be heard in full.

“I hope that one day I won’t have to talk about music,” Toussaint said in a 1974 profile for the Real Paper, a Boston alt-weekly. He was interviewed in his office upstairs at Sea-Saint, where his desk was piled high with sheet music, tapes and reel-to-reel machines. “I would like to think that the music would be able to say it all for me.”

In Los Angeles, on a flat, lawn-lined street just west of the 110/405 interchange, Nishita sits in his garage in a surf T-shirt and flip-flops. He strings a tape onto an old Technics reel-to-reel player connected to a miniature Boss MG-10 amplifier. Even through the rudimentary rig, the music snaps to life. A stuttering, marching-band horn line morphs into a fat-bellied groove and the unmistakably easygoing voice of Allen Toussaint. This is “Black Samson,” Toussaint’s unreleased 1974 soundtrack to the blaxploitation film of the same name. The music is in a class with Curtis Mayfield’s “Superfly” and Marvin Gaye’s “Trouble Man.” Reginald Toussaint confirmed that the only existing copy is currently in Nishita’s garage.

“There’s some stuff we didn’t know was missing until years later, when you’re looking for it and realize it’s not there,” he says. “A lot of people in New Orleans are still just discovering everything that was lost.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.