John Fogerty on the Grateful Dead at Woodstock: ‘They sabotaged our chance in the limelight’

As important as the original Woodstock live album and film were for documenting watershed performances by Jimi Hendrix, Santana, Joe Cocker, Sly & the Family Stone, the Who and Joan Baez, among others, they’re also noteworthy for acts they omitted: Janis Joplin, the Grateful Dead, the Band, Neil Young and Creedence Clearwater Revival, to name a few.

The reasons were varied, but one common thread for many participants who opted out of the Woodstock document was that they felt the celebrated “three days of peace and music” didn’t show them to their best advantage.

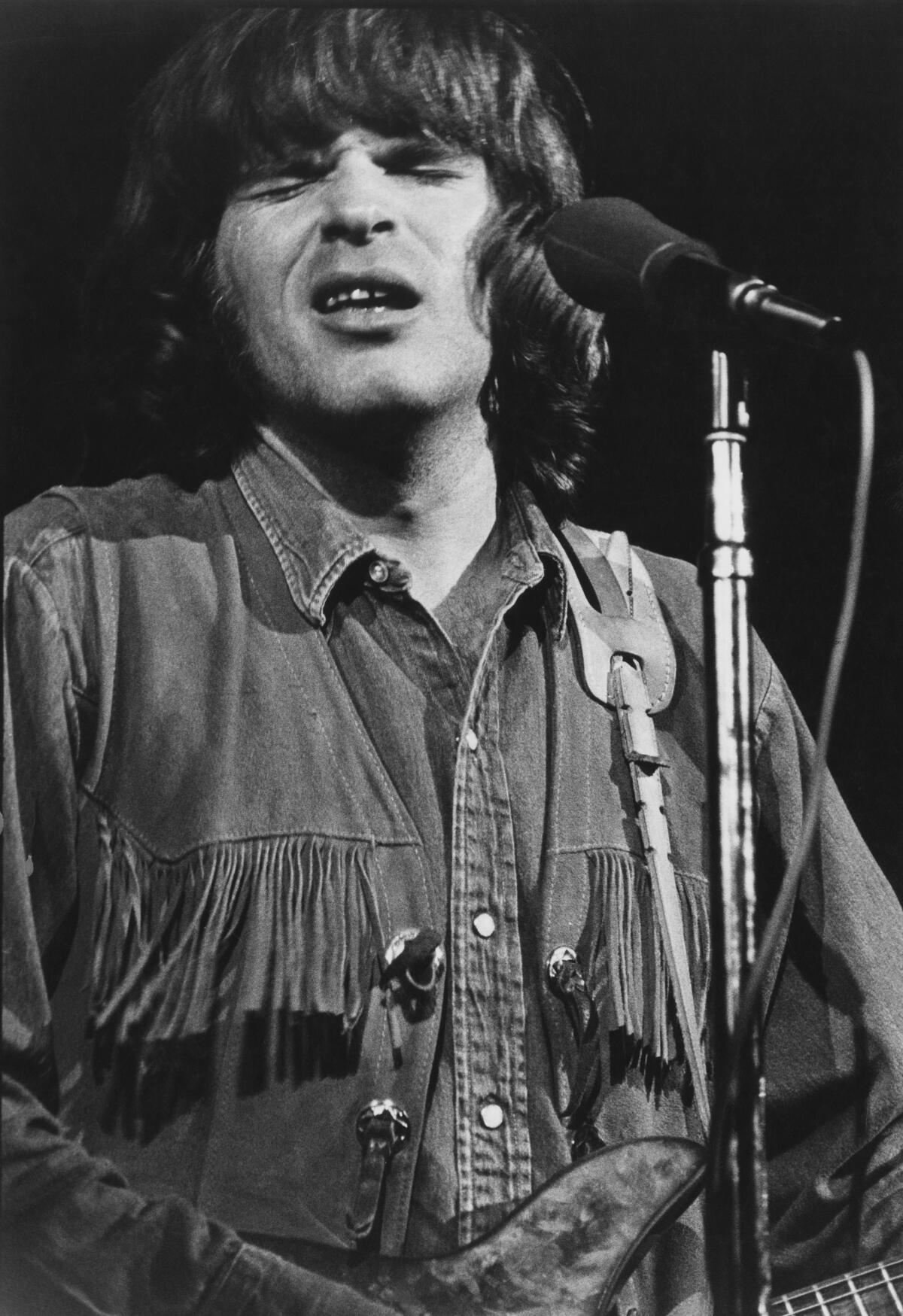

“By the time we went on it was 2:30 in the morning,” Creedence singer, songwriter and guitarist John Fogerty told The Times in a phone interview. “We played a great set, but there was almost no reaction.”

On the eve of the festival’s 50th anniversary, Fogerty, 74, recounted his role in one of the cornerstone pop culture events of the 20th century and his reasons for belatedly allowing his music to be included on the new limited-edition 38-CD Woodstock 50th anniversary box set. (Creedence’s set also is available individually as the single-disc album “Creedence Clearwater Revival: Live at Woodstock.”)

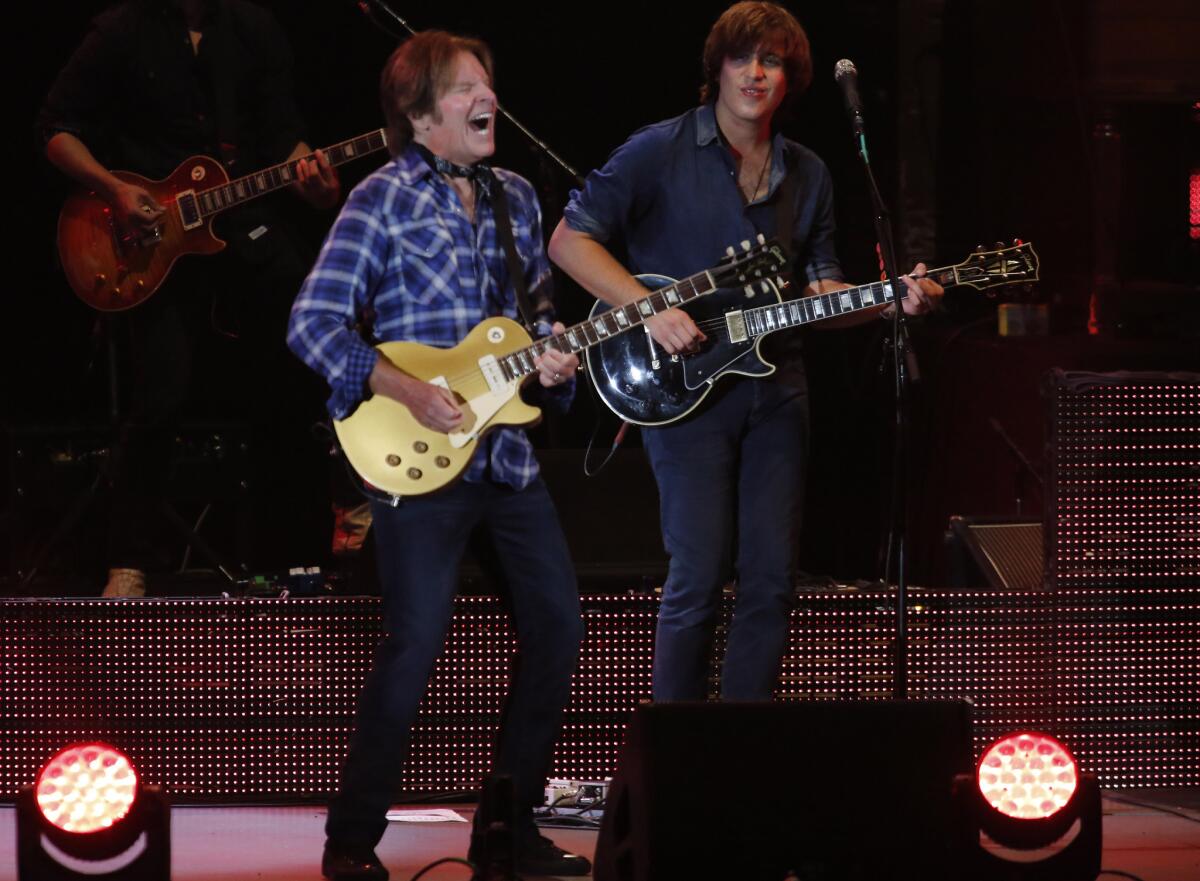

In fact, Fogerty and his modern-day band will perform Sunday at the Bethel Woods Center for the Arts, near the original Woodstock site in New York State. It’s part of his current 50 Year Trip tour celebrating a single year in which Creedence released three hit albums — “Bayou Country,” “Green River” and “Willy & the Poor Boys” — and charted eight singles, including “Proud Mary,” “Green River,” “Fortunate Son,” “Bad Moon Rising” and “Born on the Bayou,” within a 12-month span.

Fifty years later, what’s the lasting overall impression of your experience at Woodstock?

I’d been seeing a lot of billboards that said something like “Come to Woodstock for 3 days of Peace, Love and Music.” I got the call to perform in June or maybe July, which seemed pretty late in the game. I wanted to make sure Creedence got a good spot and they agreed to put us on at 9 on Saturday night. It turns out we were the first act to sign, and once we did, all the other acts fell in step. But I didn’t know this at the time. We were told we would go on after the Grateful Dead. They didn’t start until after 9, and they played for 45 minutes and I thought, “Great, we’ll be on pretty soon.” But then they started playing again, and played for another 45 minutes. They didn’t finish until after midnight. I found out in the ‘90s that they’d dropped LSD before they went on, and so there they were onstage, what do you say, pretty bewildered. [He laughs.]

We ran onstage ready to rock ’n’ roll, but everybody was just lying there in front of the stage asleep. That’s why I didn’t want it on the record or in the film. I figured at best it wouldn’t help, and at worst it might hurt us for people to see that. About halfway through, I went to the microphone and said, “We’re playing our hearts out for you and want you to have a good time.” And from the back of the field somewhere I heard a voice shout, “Don’t worry about it, John.” So in my mind, there was one guy who was awake and we finished our set for that guy.

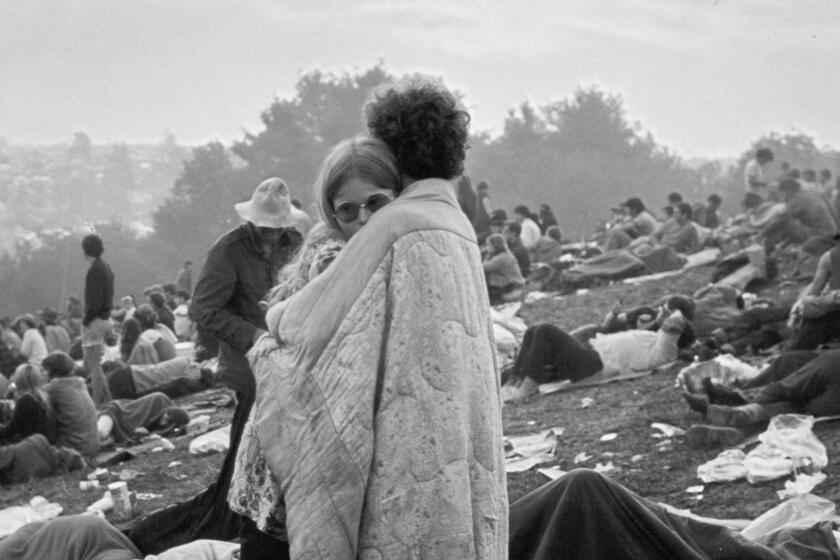

Hippiedom’s place in history is still unsettled, 50 years after the original Woodstock and as hippie-hating “Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood” is in theaters.

Were you a fan of the Dead at that time, and did their intrusion on your set color your feelings about them?

I’d seen the Dead live a few times around the Bay Area, and I knew their reputation. At the time, I was what you would call pissed off. They sabotaged our chance in the limelight. But over time, I have developed quite an affection for the Dead. They mumbled their way through a career and they outlasted the Man. They changed the paradigm by doing it their own way, and they made it work. But at Woodstock, they were just a bunch of drugged-out hippies.

What led you to allow the recording of Creedence’s complete performance to come out now?

I had never really heard the whole performance until recently; I’d just heard bits of it over time. My son Shane has heard far more of the Woodstock performance than I’ve heard. He’s mentioned it to me more and more in the last three years: “Dad, it’s really good. You ought to listen to it.” He was right.

Has your perspective on Woodstock changed over the decades?

One of the things I thought about after somebody told me that Creedence was the first act to sign, in some ways Creedence is kind of responsible for Woodstock. If I’d known that, I probably would have held out for more.

You’re playing this weekend virtually on the site where Woodstock took place — have you considered reconstructing the exact Woodstock set on Sunday?

It was a really good set, but perhaps some of it doesn’t translate [today]. Some of those songs are lesser known, like “Ninety-Nine and a Half [Just Won’t Do],” we haven’t been doing that much. I’m also a little in fear of tempting the gods, given what happened last time.

You’re also bringing your 50 Year Trip tour back to Las Vegas to extend the residency you’ve been doing there at the Wynn Encore Theater. Back in the days of Woodstock, Las Vegas was considered the antithesis of the spirit of rock ‘n’ roll. What persuaded you to play there?

As a kid growing up, you’d see Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis, Dino [Martin] and all that group playing there, and it seemed to a young kid playing rock ‘n’ roll kind of like a place they put you out to pasture. All my life, I had that attitude about Vegas and that whole casino kind of show. So it was with some trepidation I decided to give it a try. I found I really enjoyed it. It didn’t change me. I still come and play my rock ‘n’ roll show, and what I’ve found is my audience, the rock ‘n’ roll audience, comes to see me, and they expect me to be me.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.