Newsletter

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“It’s pure cinema,” Guillermo del Toro tells me via email, “affecting and gorgeous, and because it’s animation, it is absolutely a creation and not a re-creation.”

The revered Mexican director and staunch champion of animation is raving about “Robot Dreams,” a hand-drawn urban fable that received a surprise Oscar nomination earlier this year. Del Toro won that Academy Award in 2023 for his heart-rending, World War II-set “Pinocchio,” co-directed with the late Mark Gustafson.

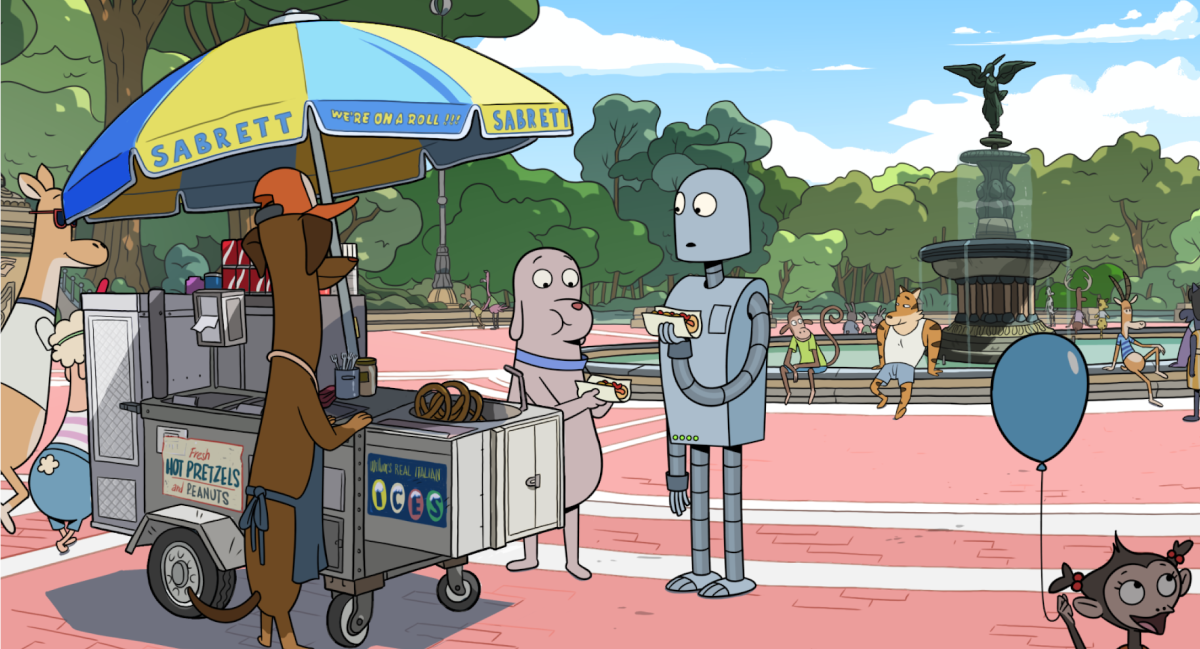

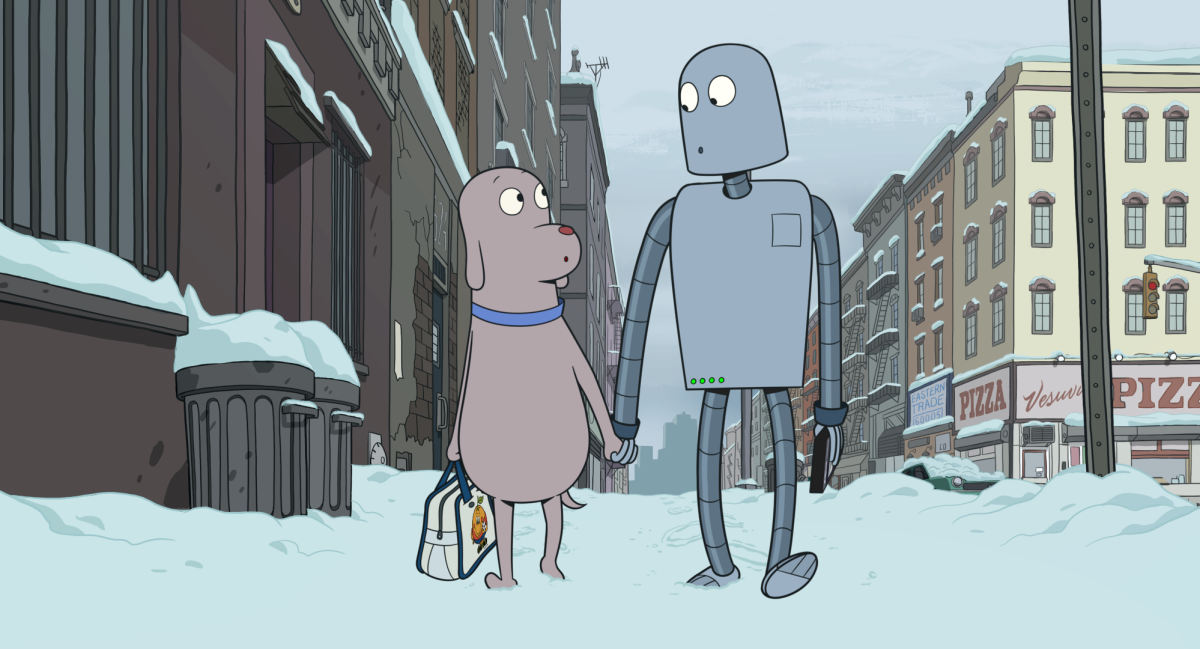

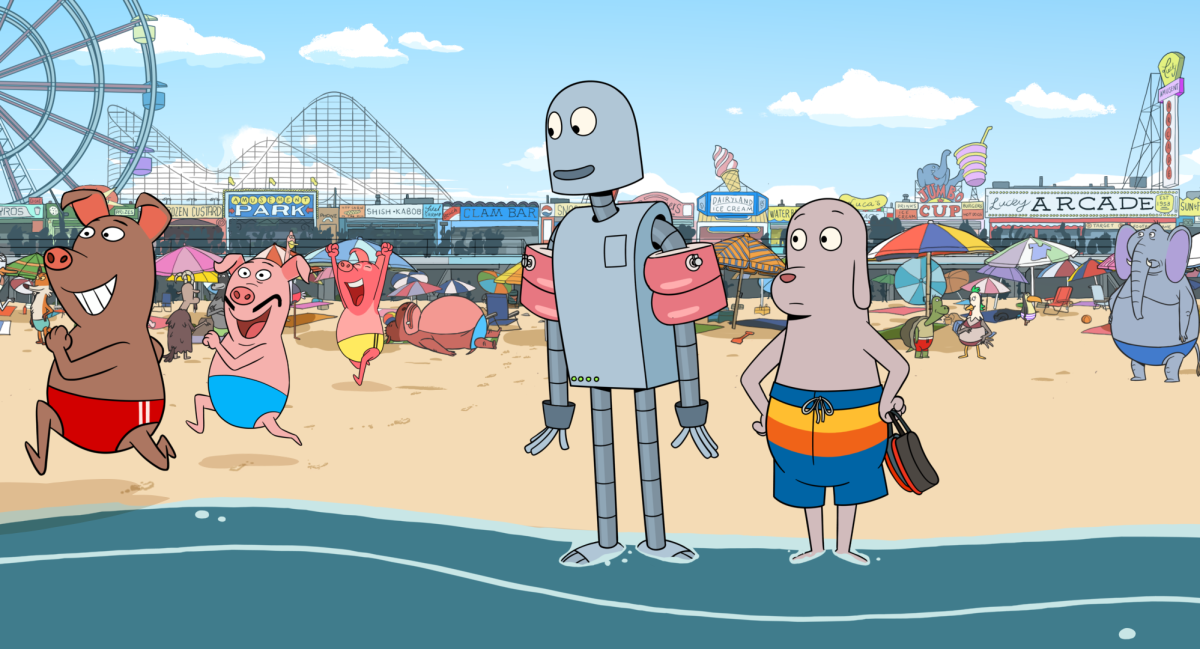

Without a single line of spoken dialogue, “Robot Dreams,” out in Los Angeles on Friday, tracks a stirring friendship from its sunny dawn to a bittersweet twilight. Feeling the weight of loneliness, Dog, a pudgy canine living in a kinetic and chaotic 1980s New York, purchases a robot friend from a late-night infomercial. Together, the fast pals frolic around the city until one fateful day Robot gets stranded at Coney Island at the end of summer.

With the beach closed for the season, Dog spends the next few months trying to break in to rescue him, while Robot dreams fantastically of getting back to his buddy.

Del Toro describes the film as “a very deep, very human story about love and loss and life after that. Adult, emotionally, but delightful and whimsical, visually and tonally.”

The movie’s Spanish writer-director, Pablo Berger, making his first foray into animation, reimagined the friendship from a 2007 graphic novel by American artist Sara Varon. “I never thought I would make an animated film, although I am a lover and great defender of animation,” Berger, 61, says in Spanish at a hotel in Beverly Hills during the week of the Oscars.

Months later, he remembers the experience of attending the Academy Awards as a “roller coaster at a theme park,” and recalls feeling ecstatic at losing the trophy that night to “The Boy and the Heron” by the Japanese master Hayao Miyazaki. (Berger had believed “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse” would be a shoo-in.)

Hollywood has already approached him with offers, both in animation and live-action, but as a director who likes to “cook over low heat,” he’s in no rush. Berger has made only four features in 20 years.

Things get a little scary on a duck family’s journey, while a dog and a robot bond without words.

Two decades ago, when Berger’s daughter was around 2 years old, he started collecting graphic novels without dialogue. “I wanted to share my love of reading and she still didn’t know how to,” he recalls. He is now up to about 100 wordless graphic novels.

Aware that Varon’s “Robot Dreams” fit the bill and had been a success in the United States, he ordered a copy in 2010 to add to his collection. “It became one of my favorites,” he says.

By then, it had been almost a decade since his 2003 debut feature, “Torremolinos 73,” an irreverent sex comedy about a salesman and his wife finding a new career path in pornographic moviemaking. It earned Berger a pair of nominations at the Goya Awards, Spain’s Oscars. And before that major success, he had already been a professor at the New York Film Academy and received an Emmy nomination for the short film “Truth and Beauty.”

But years later, he reread “Robot Dreams” to pass the time and something new had happened: an accrual of personal experience that deepened the story. Berger substituted Dog and Robot for people in his life — both of his parents had died and a relationship with one of his closest friends had soured. When he reached the end, his eyes filled with tears.

“I thought, ‘If this happened to me reading this graphic novel, how wonderful would it be if I make a movie and what happened to me also happens to the viewers?’ ” he remembers.

“I had been doing stories with happy endings and a friend told me that I was really predictable,” graphic novelist Varon, 53, says over Zoom. “I decided it was going to be a story without a happy ending about a friend who accidentally betrays another friend.”

“Robot Dreams” was her first book, one that took its time to germinate. She originally created the story of Robot and Dog to be part of an anthology of robot-related stories, but missed her deadline. Not confident in her dialogue-writing skills, Varon decided to make it purely visual. And when publishers asked her for a longer story, Varon strung together several Dog and Robot vignettes.

She has nothing but positive things to say about Berger’s take on her story. “He definitely put his mark on it,” Varon says, praising the added humor and detailed backgrounds, which are far more minimalist in her original drawings.

“It was really important to me that Pablo wanted to do it in 2-D,” she says, “because I grew up in the ’70s loving 2-D animation like ‘Underdog’ or ‘Tennessee Tuxedo.’ ”

The now-defunct animation outfit Blue Sky Studios, the company behind the “Ice Age” movies, approached Varon with interest in adapting “Robot Dreams.” In retrospect, she’s glad that offer ultimately didn’t move forward. “I wasn’t a huge fan of their style,” she recalls. “I would’ve been much more worried.”

Varon gave Berger carte blanche to transform and build on her concept and characters. “I wouldn’t have made the film if I didn’t have creative freedom,” Berger says. “Sara was incredibly generous.”

“The first time I saw the movie I was like, it’s really not my story anymore. It’s Pablo’s story now,” adds Varon.

One early yet significant change he made was to set the film in New York City, where he resided during the ’90s while studying film at New York University on a scholarship. (The graphic novel doesn’t have a determined location). Unable to physically travel to the U.S. to do research during the pre-production because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Berger relied on old photos taken by his producer and life partner Yuko Harami.

“I am not at all nostalgic, but there is an element of nostalgia for the New York I knew, for that young man who becomes a film director in New York,” Berger says.

Berger stepped into the world of animation with understandable trepidation, reliant on an art department, led by José Luis Ágreda, after working on many projects with teams of people: cinematography, production design, makeup and hairdressing departments. He leaned into his experience working with actors.

“The big difference is that, in a live-action film, the director has a super intimate

relationship with the actors and, in an animated film, the relationship that a director has is super intimate with the animators,” Berger explains.

Throughout the production, animation director Benoît Féroumont served as interpreter between Berger and the animators. A veteran in the field, Féroumont worked on 2003’s Oscar-nominated “The Triplets of Belleville,” another feature without dialogue.

“I wanted to direct cartoon characters that gave me performances full of truth, full of emotion, full of sincerity, where they are not overacting,” Berger says.

The key, just like when working with flesh-and-blood actors, was in what their eyes transmitted. “I became obsessed with the eyes of my characters, with their pupils, with the intention of their gaze,” Berger says.

Berger also knew that his tribute to New York needed New Yorkers. In the film version of “Robot Dreams,” the background characters, all anthropomorphized animals, have distinct looks: a lion with a boombox, a wiener dog selling franks and some mischievous rabbits. If you pay close attention you can see they are all involved in their own lives, going places, solving crises, having fun. A group of dedicated designers created more than a thousand distinct creatures to populate the city.

Amid all the changes Berger implemented, the one immutable aspect from Varon’s pages was her heartbreaking, resonant ending. Some people, she suggests, are not meant to stay in our lives forever, but their effect lingers long after they are gone.

“For me the only reason to make this movie was the ending,” Berger says.

“I’m glad Pablo didn’t change the ending — another studio might have been like, ‘Let’s give it a happy ending,’ ” Varon adds.

Berger believes that the audience’s strong emotional reaction to his film is due in great part to its silence, which allows its simple drawings to become symbols. “The viewer can turn these representations into whoever they want — a friend, an ex-lover, a parent,” says Berger, who believes every profound relationship has an emblematic song.

For Robot and Dog, that song is Earth, Wind & Fire’s funky and danceable 1978 single “September.” The first time we hear the track comes with a scene of rollerblading in Central Park, a moment when they were truly happy together. The tune then becomes a motif as it’s heard when Robot whistles it and then in a piano version.

While Berger had included “September” in the first draft of the screenplay, it wasn’t until much later that he realized that the lyrics “Do you remember / the 21st night of September?” had a serendipitous connection to him. Berger’s daughter was born on Sept. 21. The song reinforces the movie’s core theme: memory.

“Selective memory is a balm in facing loss,” says Berger. “It allows us to keep those wonderful memories, which make our loved ones who are no longer with us stay alive.” In honoring his own missed connections and separations, he’s made a film that is, in itself, close to unforgettable.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.