Column: In Lady Jessica, ‘Dune’ created an all-time movie mom. Then ‘Part Two’ ruined her

Warning: Spoilers ahead. Absolutely do not read this if you have not seen “Dune: Part Two.” I mean it.

I knew I was going to have problems with “Dune: Part Two” when it opened with the image of a fetus.

If female autonomy was not currently under attack from so many sides, my stomach might not have clenched quite so dramatically as those undeveloped eyes and barely formed limbs marked reentrance into the sprawling tale of Paul (last-of-his-house) Atreides, his pregnant mother and those around them.

But a lot has happened since the first part of Denis Villeneuve’s magnificent adaptation of Frank Herbert’s dystopian epic premiered in 2021. The overturning of Roe vs. Wade in 2022 had led to an increasing emphasis on “fetal rights,” including the recent determination by the Alabama Supreme Court that frozen fertilized eggs are, legally, children.

Which “Dune: Part Two” only emphasizes by the appearance of this fetus, which soon will become sentient and begin speaking through her mother, the Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson).

Once a kick-ass member of a mysteriously powerful order of priestesses, Lady Jessica dramatically saves her son’s life early in the film only to slowly turn into a glorified baby monitor.

She does other things as well — namely, push Paul (Timothée Chalamet) to accept his “destiny” as the much-prophesied “messiah” (and away from the loving arms of the nonroyal warrior Chani, played by Zendaya) with the ferocious single-mindedness of Angela Lansbury in “The Manchurian Candidate.”

But as the movie progresses, Lady Jessica increasingly serves only to deliver communiqués to Paul from his unborn sister, who seems way more concerned with his reluctance to start an interstellar holy war than, say, the development of her own limbs.

For the record, I thoroughly enjoyed “Dune: Part Two,” which I saw on Saturday morning because I could not find another showing that was not completely sold out. And I get it. It’s science fiction and, like many sci-fi and fantasy writers, Herbert created a complex and fully realized world based on a melange of ancient intercultural mythology and futuristic imaginings that highlight the problems of history and the modern world.

All of which Villeneuve has brought to vivid, sand-in-your-teeth, hydration-hoarding life.

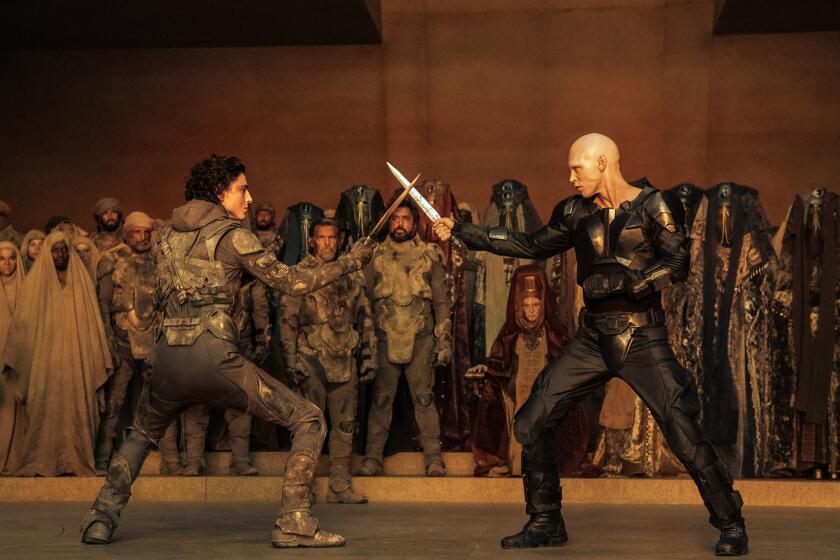

Stirring and sublimely epic, the conclusion to Denis Villeneuve’s atmospheric first half climaxes with a showdown between Timothée Chalamet and Austin Butler.

The “Dune” series, and Villeneuve’s two-part film adaptation of its first book, is a true epic, with many alarmingly resonant themes. In the far distant future, an interplanetary emperor pits noble houses of many planets against one another as they jockey for power, particularly over the harvesting of spice, a near-magical waste product of the giant sandworms that live on Arrakis. This barren world also is inhabited by the beleaguered Fremen, whose eyes have gone blue from long contact with spice and who are considered subhuman by the other planets and their armies.

For many Fremen, the only hope is the coming of a messiah that has long been promised.

So feudalism, check; environmental exploitation, check; colonialism, racism and the power of religion, check, check and check.

Behind it all, however, is the Bene Gesserit, a group of priestesses who possess, among other things, the ability to bend the will of others through use of “the voice,” to determine the gender of their children and to survive poisoning. They also have a big-picture scheme that they are implementing through years of prophecy and eugenics: producing a male messiah, over whom they have control, to free the world. Or whatever. (The Bene Gesserit don’t seem particularly big on freedom as most folks define it.)

I am 100% behind any story that includes an all-powerful band of far-seeing priestesses, even if they are super-mean and manipulative, and the regular side-snark about men not being up to the physical and mental challenge of ruling did not go unappreciated. Also, the group’s leader is played by Charlotte Rampling, which is as it should be since she is the only actor living who can project both world-weary wisdom and utter ruthlessness while wearing an absurdly high hat and a nearly impenetrable black veil.

In the first film, her relationship with acolyte Lady Jessica plays a bit like a perpetually skeptical head of the CIA dealing with an exasperating but productive rogue agent. And Lady Jessica lives up to the role. Yes, Paul is “Dune’s” main character, haunted by visions of an apocalypse that will follow his acceptance of his destiny, but in the first movie he is bonded to his mother in a way rarely seen in film.

As in respectfully, lovingly and nontoxically.

After Paul’s father is forced by the emperor into taking over spice production on Arrakis and then slaughtered, along with the rest of House Atreides, Paul and Lady Jessica flee into the desert. Their adventure is one of equals. When they meet up with the initially hostile Fremen, it isn’t just Paul who proves himself a superior warrior; Lady Jessica may be pregnant, but that doesn’t affect her fighting skills.

Which is why I went into the second film with such high girl-power hopes, only to be confronted with a giant fetus.

Elvis has left the galaxy: Austin Butler and director Denis Villeneuve discuss bringing Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen, the vicious villain of ‘Dune: Part Two,’ to life.

Things change for the mother-son pair, and quickly. First Paul falls in love with Chani, a Fremen warrior who sees the messiah prophecy as overlord propaganda, which naturally threatens to back-burner his mom. Indeed, in Herbert’s version, the pair live with the Fremen for years, during which time Lady Jessica gives birth to her daughter Alia and fades into the background.

Villeneuve, smartly wanting to keep the magnetic Lady Jessica center stage, condenses the original chronology; the second film picks up shortly after the events of the first. As in the book, Lady Jessica is forced to become the Fremen’s Reverend Mother by drinking “the water of life” — a poisonous liquid taken from sandworms that downloads the memory of all her ancestors. Only a Bene Gesserit can neutralize the poison, which, we are told repeatedly, would kill any man. Unfortunately, she does this while pregnant, granting her fetus the same power.

In the book, this results in a wickedly smart and perilous toddler-priestess. Hoping, perhaps, to avoid the creepy woman/child of the final “Twilight” movies, Villeneuve gives us instead a prenatal version of Alia — “Look Who’s Talking Dune: A Womb With a View.” Unfortunately, this means the wildly independent Lady Jessica we knew and loved is gone. Heavily pregnant, she is given little more to say than a messiah’s mom’s version of “Sing out, Louise” and whatever her still nonviable fetus tells her to.

Also, she taught Paul how to use “the voice,” which I think will turn out to be a Big Mistake.

All of which only highlights the contradiction at the heart of the tale: For all their superpowers, the Bene Gesserit’s main purpose appears to be reproduction. Self-controlled reproduction, to be sure, down to the baby’s gender, but with the purpose of producing a male leader whom they hope to “control” from the shadows.

In other words, the kind of boy-mom power adjacency most women have had to be content with for centuries. Considering the medieval nature of “Dune’s” power structure — warring royal houses, sacred seal rings, steadfast (and treasonous) knights — that makes a certain amount of narrative sense. Throughout history, even royal women were tied to the production, and fates, of their sons.

Still, given the enormous promise of superpowered priestesses — honestly, if they can control people with their voices, how are they not completely in charge? — including a mother who can defy her very scary boss, keep her cool in a helicopter crash and hold her own in a knife fight, it was a bit of a letdown to realize that the women of “Dune’s” universe are still defined mostly by their ability to give birth.

Even Florence Pugh’s Princess Irulan, daughter of the Emperor, was used mostly as marriage bait. (Though she too is a Bene Gesserit and her name begins “i-rul,” so here’s hoping.)

Only Chani manages to escape the trap of prophecy and bloodlines, of arranged marriage, designer babies and the dream of world domination. And since the final image is of her, a full-grown, nonpregnant woman literally turning her back on the whole mess and preparing to ride a sandworm into the sunset, maybe there is hope for us all.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.