Review: Not just a Leonard Bernstein biopic, ‘Maestro’ is one of the year’s great marriage stories

“The world wants us to be only one thing, and I find that deplorable.” That’s Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper), who, in his late 20s, has already been many successful things: pianist, composer, teacher, seducer, bon vivant and, of course, conductor. Revered for his prodigious talent and larger-than-life charisma, he also has been criticized by those who’d like to see him focus on conducting and put away his silly stage musicals and other dilettantish distractions. (Lovers of “On the Town,” “West Side Story,” “Candide” and “On the Waterfront” can be eternally grateful that he ignored them.)

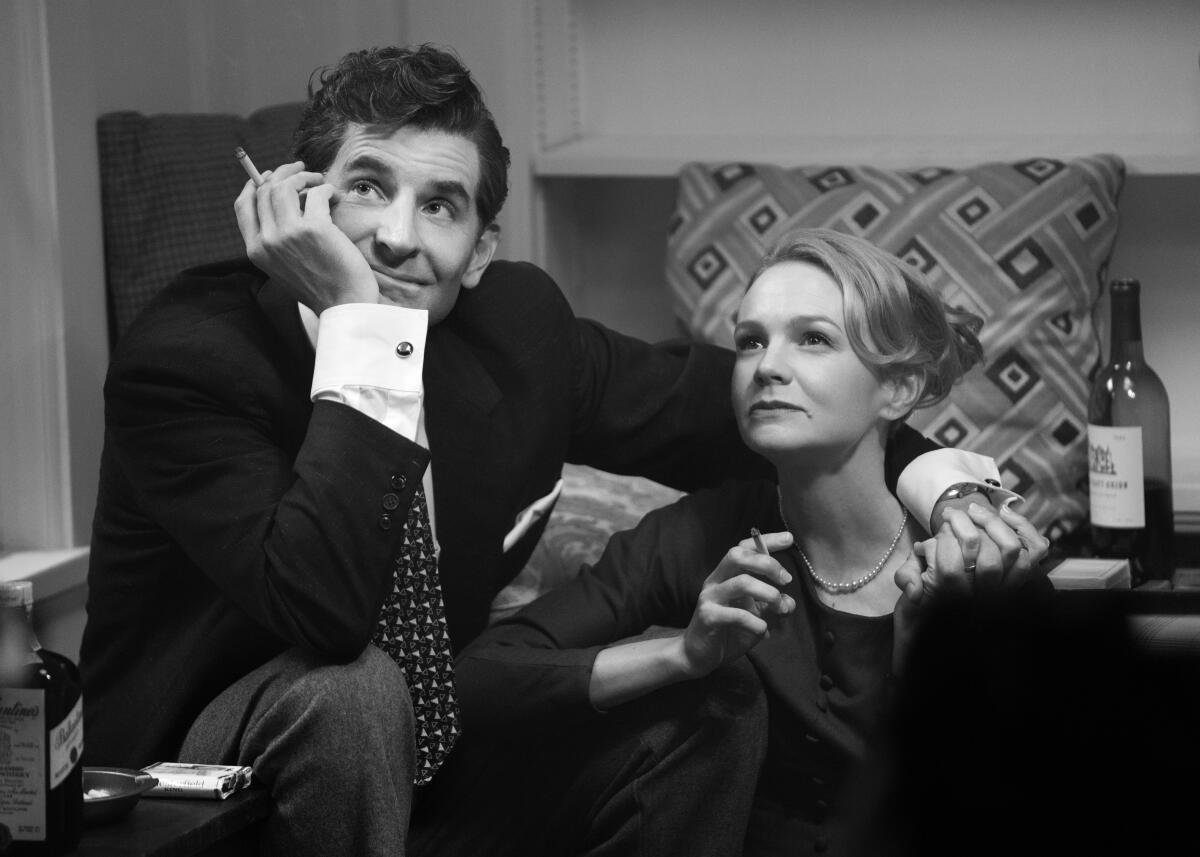

Lenny shares his frustrations with Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan), whom he’s just met at a party and claims to recognize as a kindred spirit. Felicia, born in Costa Rica and raised in Chile, has come to New York to study piano and acting, and Lenny, clearly entranced, insists that her talents and ambitions are as versatile as his own. She isn’t so sure, and history will partly confirm her suspicions. While Felicia will garner some fame onstage and on television, her best-known and longest-running role will be Mrs. Leonard Bernstein, a performance that requires her to take care of their home, raise their three children and turn as blind an eye as possible to her husband’s affairs with men.

The magnificent new drama “Maestro” is skilled in the art of multitasking itself, and not just because Cooper directed, produced and (with Josh Singer) co-wrote the movie as well as starring in it. Five years after his filmmaking debut, “A Star Is Born,” the director has returned with another admirably complicated and generously balanced portrait of a tempestuous showbiz marriage, this one drawn from real life. With narrative elegance, formal brio and exquisite feeling, Cooper ushers Felicia into the spotlight and sometimes shunts the attention-hogging Lenny off into the wings. (It’s hardly an accident that the onscreen title appears over an image of Felicia, or that Mulligan receives top billing.) In doing so, the director offers up a subtle yet significant corrective to some of the dramatic oversights and patriarchal assumptions endemic to the great-man biopic.

Not that “Maestro” flouts every convention of its Oscar-friendly subgenre. Like more than a few movies about real-life celebrities, it boasts dazzlingly transformative feats of acting, some of which have already generated controversy. (Certain viewers have raised objections to the casting of Mulligan as a Latin American woman and Cooper as a Jewish man, especially since his many prosthetic enhancements include a slightly enlarged nose.) And like most cinematic portraits of popular artists, the movie sacrifices career completism for a kind of body-of-work shorthand, guiding us on a deft expository tour of greatest hits and undersung gems.

In this case, though, the streamlining feels more purposeful than reductive. Cooper and Singer have distilled the long, rich and uncontainable arc of Bernstein’s career into an array of gorgeous (if truncated) performances, witty allusions and showstopping needle drops, along with the odd “Eureka!” moment. When Lenny drives home with a young lover (Gideon Glick) in tow, we hear the brassy opening notes from “West Side Story,” as though in anticipation of a marital rumble. A few beats later, Lenny emerges with the finished score of his famously polarizing 1971 theater piece, “Mass,” only to find that Felicia, in a fit of exasperation, has managed to upstage him.

But if the Bernsteins’ discord provides Cooper and especially Mulligan with their most forceful dramatic moments, it is also just one scorching motif in a marital symphony of consoling grace and devastating tenderness. The movie begins, tellingly, with a twilight-years framing device: Playing a somber piano piece from his 1983 opera, “A Quiet Place,” a white-haired, melancholy Lenny plunges us into the memories of his early life in music, and also of the late wife he imperfectly but undeniably loved.

If that sounds like a cliché ripe for “Walk Hard”-style skewering, it doesn’t play that way. The joyous first third of “Maestro,” filmed in silvery black-and-white by cinematographer Matthew Libatique (“A Star Is Born,” “Black Swan”), has a freewheeling kineticism that expresses Lenny’s boundless brilliance. It’s 1943 when he receives his big break, making an electrifying short-notice debut as guest conductor of the New York Philharmonic. Cooper stages the fateful phone call beautifully, in a composition that turns a nearly blacked-out window into a stage curtain, just waiting to be lifted.

From there, in one sweeping motion, the camera transports Lenny from his apartment to Carnegie Hall, a formal conceit that suggests the blur of his personal and professional lives (and also revels in the cleverness of Kevin Thompson’s onstage/offstage production design). Lenny’s inner circle is a who’s-who of the Manhattan musical and theatrical set; admirers of the period will recognize names like Aaron Copland, Betty Comden, Adolph Green and Ellen Adler. The one-liners are crisp, the mood effervescent and urbane, the sexual mores ambiguous. Lenny sleeps with women but mostly men, one of whom (a briefly seen, achingly poignant Matt Bomer) he too callously throws aside not long after his younger sister, Shirley (a tart Sarah Silverman), introduces him to Felicia.

She captivates Lenny and also challenges him, noting that his optimism about their joint artistic potential doesn’t take into account, among other things, the inequalities of gender. Felicia knows that neither work nor life with Lenny will be easy; she also grasps the nature of his sexual identity well before she lets on, which doesn’t entirely free her from an element of self-delusion. One particularly inventive sequence, which casts Lenny as one of the sailors from “On the Town,” turns these divided desires into a literal dance, an ode to the beauty of the male form as well as an expression of Lenny’s deep attraction to Felicia. Here and elsewhere, “Maestro” holds its contradictions in balance; it sees the complexity and the tragedy of Lenny and Felicia’s romance, and also its undeniable tenderness and passion.

By the time the picture shifts from monochrome to color, in the early 1970s, Lenny and Felicia have been married for years, with three children and a Connecticut country house to go with their Upper West Side penthouse. His success has been stratospheric, hers rather less so. There are bustling parties, casual family hangouts and some quietly lovely grace notes courtesy of the Bernsteins’ eldest child, Jamie (Maya Hawke). Over time, Libatique’s camera slows down and sometimes comes to a standstill, no longer dancing with Lenny and Felicia but instead observing them and their arguments from a chilly distance — a downbeat formal shift that works beautifully in concert, so to speak, with the characters themselves.

Lenny, who once drew such energy from the dynamism of the camera, now seems to wilt under its gaze, as though diminished by the ever-growing gap between himself and the audience. By contrast, the long-neglected Felicia grows in emotional stature, her exasperation at her husband’s serial infidelity hardening into a concentrated fury. Mulligan shows us Felicia’s ferocity but also her delicacy, her resignation at dwelling in her husband’s artistic shadow and her final, wrenching acknowledgment of how much she needs him, flawed and faithless though he may be. She also illuminates pockets of Felicia’s acting career, notably with a 1977 appearance on the arts anthology series “Camera Three,” shortly before she’s diagnosed with cancer.

Mulligan is so good here that she lays bare some of her co-star’s more studied artifice, including a few overly imitative Bernstein-isms and some affectedly nasal vocal delivery. But Cooper’s performance is its own kind of marvel, too rich to be reduced to the single cosmetic detail that has caused such outsize controversy. The debate over the merits of a prosthetic schnoz, or whether non-Jewish actors should play Jewish characters, won’t be settled here (although film writer Mark Harris came as close as anyone has in a recent, supremely nuanced Slate essay). Crucially, though, we believe Cooper as Bernstein not because of their physical resemblance, which is remarkable enough, but because of how the actor’s star wattage merges so completely with Lenny’s own.

It’s telling that, a powerfully cathartic 1976 performance of Mahler’s Second Symphony aside, Cooper’s time at the podium is fairly limited. More often he conveys Lenny’s love of music, and his love of people, through the sheer ebullience of his language. He reminds us that Bernstein was not just a great musician but a great communicator of music, someone who fused a deep knowledge of history and theory with the instincts of a born teacher and showman. One terrific scene, in which an older Lenny gently corrects a young student’s conducting technique, could be a direct rebuke of his chillier fictional protégée, Lydia Tár. (Or maybe not, given Lenny’s own well-known fondness for cultivating attractive young talents.)

Lenny’s warmth and generosity are legendary, which doesn’t mean he isn’t also capable of cruelty, manipulation and neglect. At her most furious, Felicia rips into Lenny for using his genius as a shield, a means of keeping his loved ones at a distance. At her most forgiving, she refutes her own charge, acknowledging that Lenny’s passion for people and his hunger for music flow, inextricably, from the same source. It’s the particular insight of “Maestro” to allow both these conclusions their measure of truth. We are never only one thing, least of all to the ones we love.

'Maestro'

Rating: R, for some language and drug use

Running time: 2 hours, 9 minutes

Playing: Starts Wednesday at the Egyptian Theatre Hollywood and the Landmark Westwood; starts streaming Dec. 20 on Netflix

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.