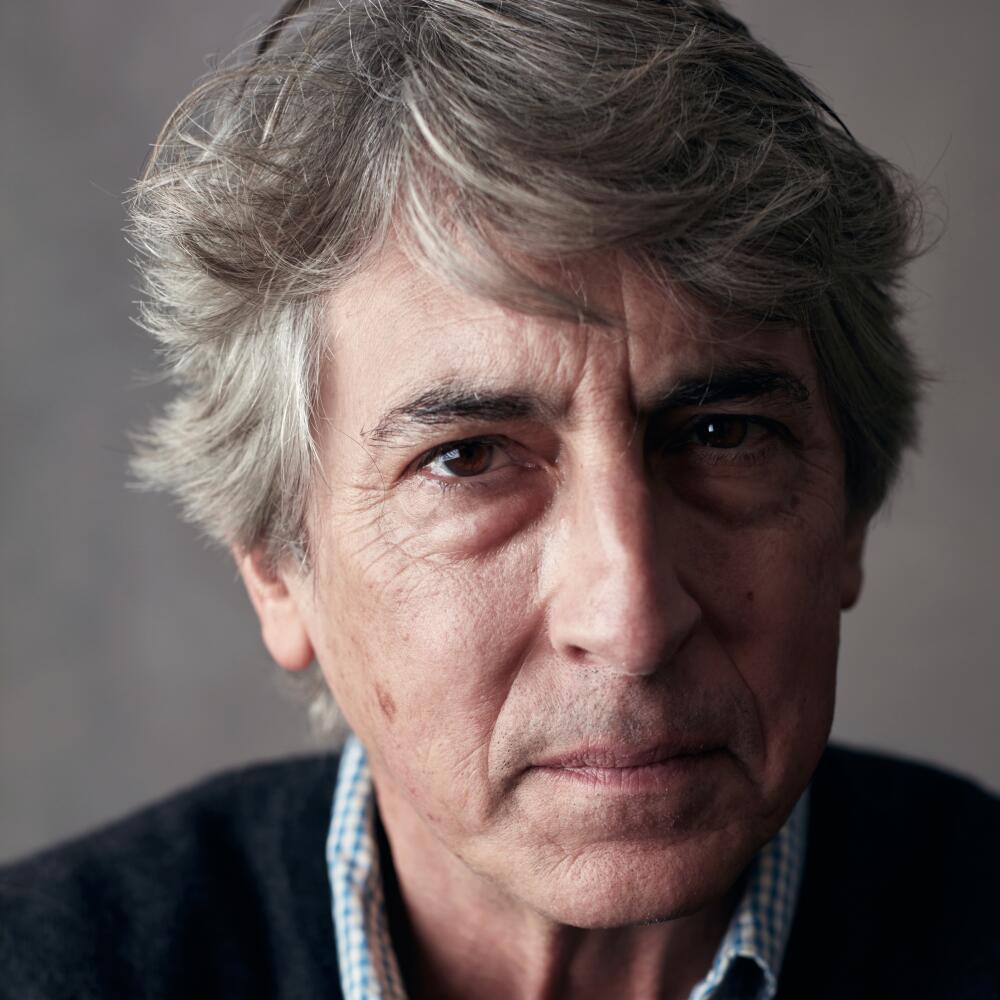

“A Film By,” the most omnipresent of onscreen designations, is beloved of first-time directors and frazzled veterans alike. One picture you won’t find it on, however, is “The Holdovers.” What you see instead is “An Alexander Payne Movie.” The reason for the change is both simple and complex: “The older I get,” Payne says with conviction, “I just want to make movies.”

It’s not like the 62-year-old filmmaker lacks “A Film By” credentials. He’s won the adapted screenplay Oscar twice (“Sideways,” “The Descendents”), been nominated for director for those films plus “Nebraska,” and has guided seven actors, including Jack Nicholson and George Clooney, to nominations.

So why did he put the word “movie” on his latest, set to open Friday with some of the best advance notices Payne has gotten in years?

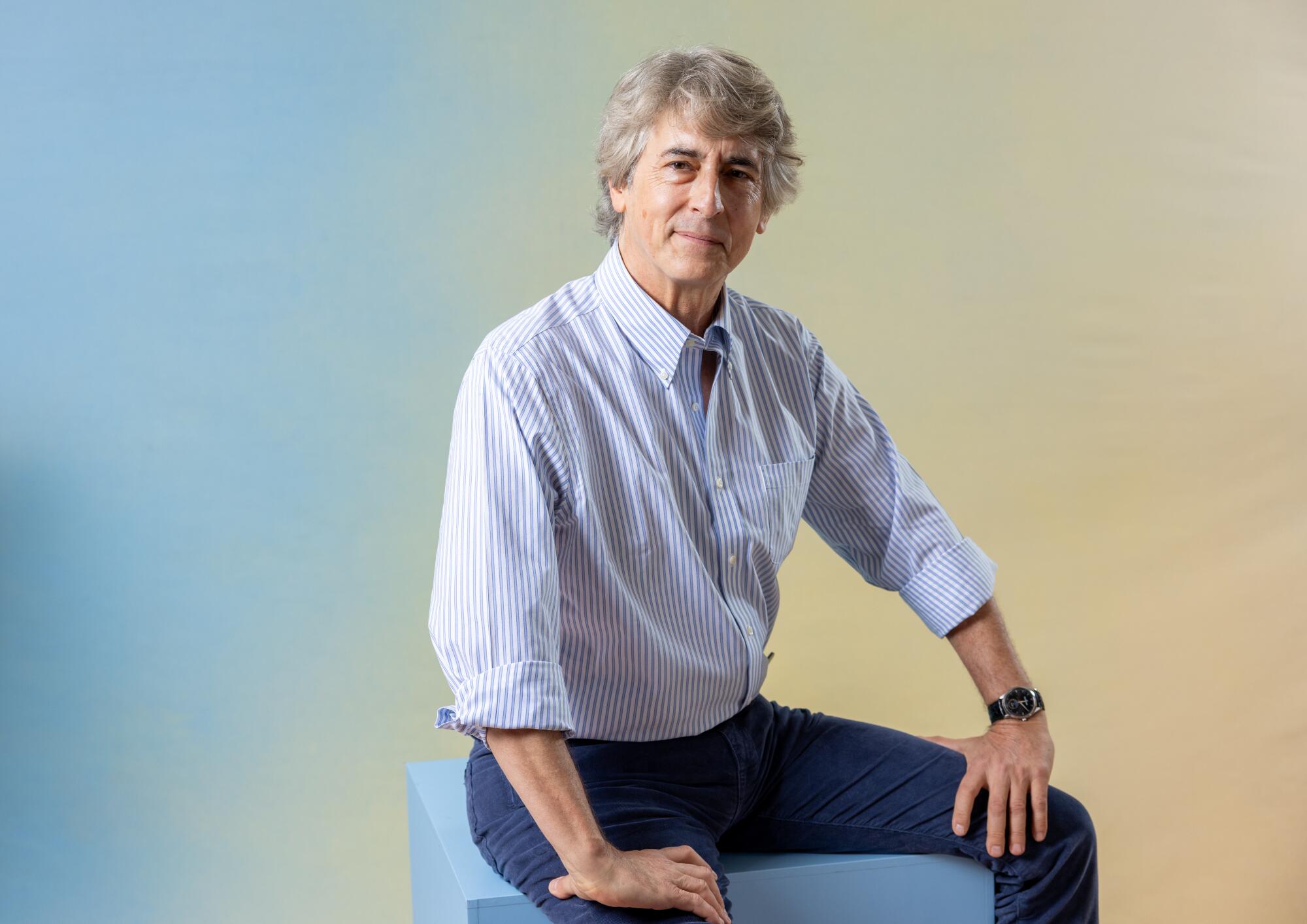

“I want to be a student of classical film style, well-acted with good literate storylines, elegantly and efficiently made,” the director, wearing a stylish pale blue button-down shirt for a Zoom call from a New York hotel, explains. “There’s a pretentiousness to trying to be unpretentious, to which I plead guilty. But it’s not that I want the director to be invisible. I want the elegance of film style to be about the story and characters, not about me. Instead of ‘look at me,’ it’s ‘look at the story, look at the characters, maybe by extension look at yourself.’”

As those thoughts indicate, Payne is precise, articulate and sure of himself — a filmmaker who knows what he wants and how to achieve it. Which doesn’t mean that a lot about “The Holdovers,” coming after a 10-year period where only one of his films made it to release, didn’t come out of nowhere and surprise him. It did.

It all started at Telluride about a dozen years ago, where Payne, a festival regular, says he always makes it a point to see the old restored classics. (“The new movies will be shoved down my throat soon enough,” he says.) This particular year, Payne watched “Merlusse” a little-known 1935 film by beloved French director Marcel Pagnol, concerning an unpopular boarding school teacher forced to babysit students with nowhere to go during Christmas break.

“I thought, ‘That’s a good idea for a movie,’” Payne recalls, but lacking private-school life experience, he mentally filed it away.

Cut to five years ago, when screenwriter and showrunner David Hemingson (“Kitchen Confidential”) sent Payne a pilot to direct, one that was set in that elite boys-school world. “I got in touch with him and said, ‘I don’t want to make your pilot, but would you consider this idea?’” the filmmaker says. Hemingson was amenable, which led to what Payne, who usually writes his scripts himself or with longtime collaborator Jim Taylor, calls “my first experience in directing a writer. I gave him the premise, there were three, four, five storylines I shot down before we agreed on one, and then he was off to the races. I’m happy to report it was a very rewarding collaboration, we wound up with a script we both feel is very personal to us.”

That story, set in 1970, has curmudgeonly boarding school teacher Paul Hunham, prone to characterizing his charges as “lazy, vulgar, rancid little philistines,” ending up spending the holidays with equally disenchanted student Angus Tully and Barton Academy’s kitchen chef Mary, who is contending with a sadness of her own.

Paul Giamatti in the teacher role was a snap to cast, with Payne noting “as you can imagine, I’ve been dying to work with him since ‘Sideways,’ but I am slow on the screenwriting front.” He even named the character Paul and called the actor early on to alert him to the prospect.

“When you cast someone, you do so because you’re curious to see what he or she is going to do with the part,” the director explains, citing the same dynamic with “My Name Is Dolomite’s” Da’Vine Joy Randolph as Mary. “When you tack on the cook character, you’ve got some nice poignancy with which to fashion a comedy,” he says. “Her part is somewhat comic but mostly dramatic and when you have that, I like to have actors with comic chops. It keeps their performance from being too dreary.”

If these two parts were relatively straightforward to cast, the situation with downbeat teen Angus Tully was anything but. When word got out that casting was open for this particular part, Payne says, “we got 800 kids sending in auditions, but no one could play Angus to our satisfaction, which led us to do something we always said we would do: speak to the drama departments of the four private schools we were shooting at. And there he was.”

He was Dominic Sessa, now in his second year at Carnegie Mellon but at the time a senior at Deerfield Academy. He’d done considerable stage work at the school but had never been in front of a camera, not even for a student film. That, however, didn’t stop him from doing moving and exceptional work as the mop-haired Angus. “A big reason to cast him was that he had the right damn hair,” Payne jokes. “We might not have cast him otherwise.”

A casting director spotted Sessa first, then Payne met with the young man. “We did what you always do with kids like that, you keep auditioning them to see how bullet-proof they are, and he kept getting better,” the director reports. “We put him together with Paul and he immediately identified talent in this kid. There was no UCLA Extension course in film-acting technique involved, he was really just born with it. To find someone in the proverbial ‘out of obscurity’ — it’s a miracle.”

What makes “The Holdovers” (very much including Sessa’s performance) such a pleasure to watch is the adroit way it walks the line between sharpness and sentiment, managing a difficult balancing act that Payne jokes he can pull off because “I’ve had weeks of experience.” Famously unsparing since his earliest work, he prefers to say his films are “emotional. You want emotion, but not schmaltz. My first films, like ‘Citizen Ruth,’ were so cynical, more satiric, and I’ve been saying for years that comedy directors, like George Stevens, Leo McCarey and Frank Capra, are most adept at emotion. Because they fear schmaltz, they are able to employ emotional effects with great care.”

The pre-release success of “The Holdovers” is especially satisfying coming as it does after the last decade, a period which saw only one Payne-directed film, the mildly received “Downsizing,” in theatrical release. Other films almost happened, like “The Menu” and “The Burial,” but none came to fruition with him involved, something the director views simply as part of the way the business works. “We all flirt with different things,” he says. “Sometimes things work out, sometimes they don’t.” Though it fell during that period, Payne says Rose McGowan’s allegation of statutory rape, which he has denied in detail, did not affect his career. “It kind of coincided with the pandemic,” he says. “I was writing. There was not a whole lot going on anyway. It came and went and that’s it.”

The only almost-project that still rankles Payne is an untitled father-daughter road trip movie starring Mads Mikkelsen on which Netflix pulled the plug in 2019, five days before production was scheduled to begin. “The writer of the source material, who I won’t identify but whose initials are Karl Ove Knausgård,” Payne says, “read the script late in the process, and language in the contract allowed him to exercise some kind of kibosh. It was very threatening. That one hurt.”

As a student of film history, Payne knows well the up-and-down cycles of cinematic careers. “Quentin Tarantino has posited that directors and actors are given 10-year periods when what you do touches the zeitgeist,” Payne says. He feels those periods can recur.

“Those very prolific directors, the guys in the studio system who made three films a year, I envy them all for how much more craft they had,” he says, hopeful of the possibility of more to come. “Following either success or failure, there’s only one word to say: next.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.