Review: Sandra Hüller acquits herself brilliantly in the superb ‘Anatomy of a Fall’

One of the many mysteries in “Anatomy of a Fall,” the enthralling new thriller from the director Justine Triet, is just how much we should trust its depiction of the French justice system. Most Americans know to watch their legal dramas with a measure of skepticism and a disdain for courtroom histrionics; those of us who’ve never spent (or done) time in Grenoble, however, may be bewildered by some of the local specifics of this movie’s murder trial, with its unfamiliar rules and anything-goes atmosphere. The accused is given an elevated, arena-style perch from which she can survey, and freely weigh in on, the rhetorical circus unfolding below. The attorneys are almost parodically French in their love of theoretical discourse, although even they have their limits. At one point, one snaps at the other: “Must we enter into a literary debate?”

Mais oui, we must. The defendant, after all, is Sandra Voyter (a stunning Sandra Hüller), a successful fiction writer who stands accused of killing her less-successful fiction-writer husband, Samuel (Samuel Theis). The peevish prosecutor (a swattable Antoine Reinartz), perhaps aware of how circumstantial much of the evidence is, has desperately taken to searching Sandra’s novels for clues. Did she steal her best ideas from Samuel, inflaming the professional jealousy and emotional chaos of their unhappy union? Do her stories, many of them drawn from real-life experience, illuminate the workings of a depraved homicidal mind? “An author is not her characters,” Sandra’s attorney reasonably objects, insisting that they focus on the facts.

Easier said than done. Less a whodunit than a who-spun-it, “Anatomy of a Fall,” which won the Palme d’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, spends two-and-a-half hours demolishing the very idea of empirical, observable truth. From its witty opening image of a ball bouncing down a flight of stairs — one step at a time, a seemingly accidental but carefully engineered tumble — Triet’s movie is a monument to the ambiguous and unknown, a labyrinth of half-glimpsed causes and vague, sinister effects. The early scenes, set in Sandra and Samuel’s cozy-looking chalet in the French Alps, are charged with a tension as undeniable as it is hard to articulate. An interview of sorts seems to be taking place, though it’s not always clear who’s being questioned, Sandra or Zoé (Camille Rutherford), the conspicuously attractive graduate student who’s come to visit. Samuel remains unseen but soon makes himself heard, blasting his music from upstairs at such insufferable peak volume that Sandra and Zoé are forced to cut their meeting short.

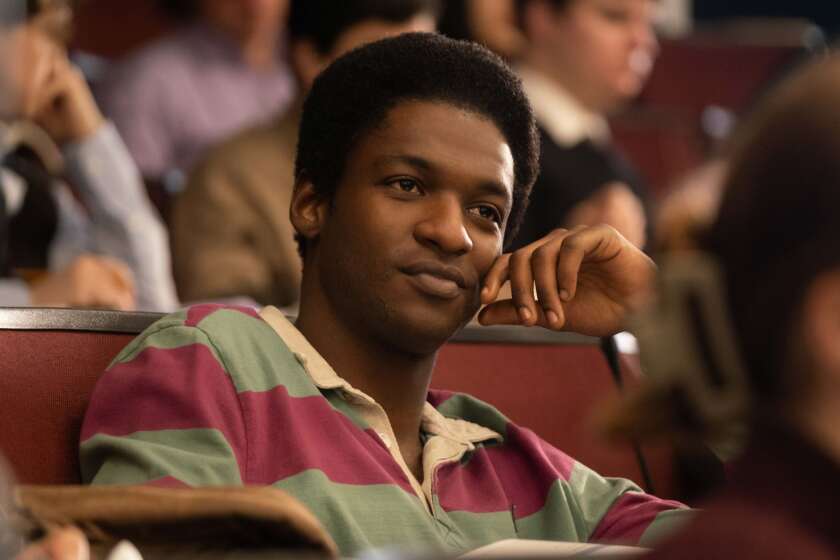

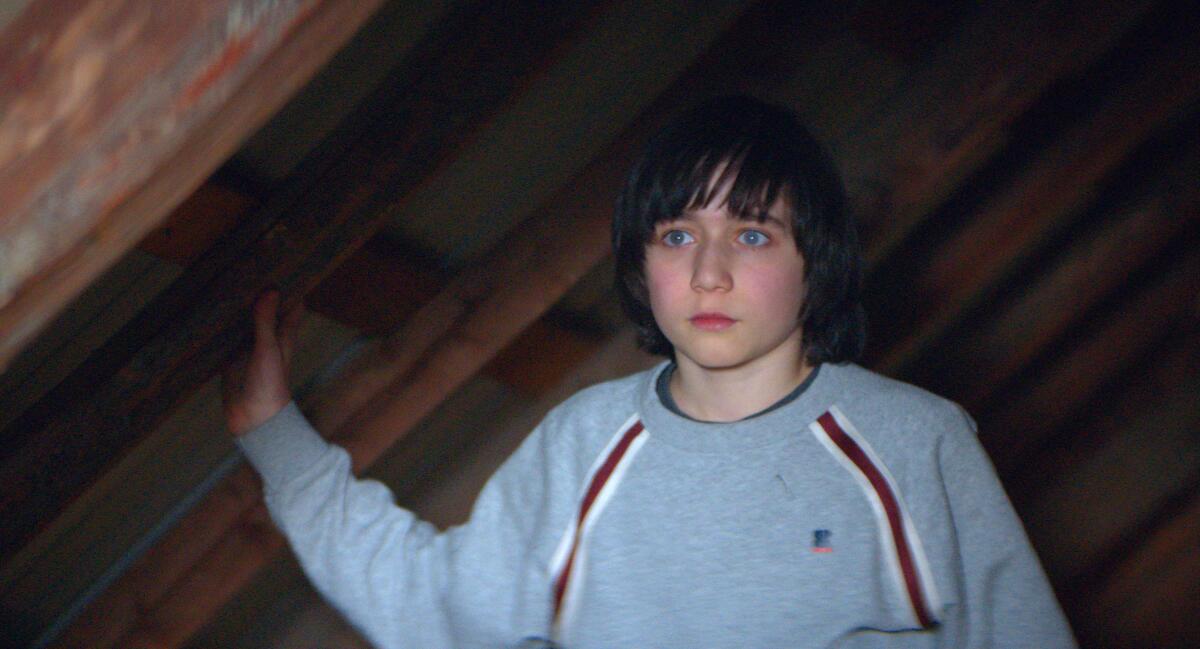

The song we hear is an instrumental cover of 50 Cent’s “P.I.M.P.,” and even without the audible refrain of “But a bitch can’t get a dollar out of me,” the aggression behind the choice is unmistakable. Some time later, we finally lay eyes on Samuel himself; he is dead outside in the snow, bleeding heavily from a head wound. His body is discovered by his and Sandra’s 11-year-old son, Daniel (Milo Machado Graner), who has a severe visual impairment and is thus endowed, in this narrative’s irony-rich scheme, with Tiresian powers of perception. Daniel is aided in his discovery by his faithful border collie, Snoop — a sly reference, perhaps, to Snoop Dogg, who once recorded a remix of “P.I.M.P.”? As with so much in this movie, Triet isn’t saying.

Instead she and her co-writer, Arthur Harari, allow riddles and possibilities to multiply. The best-case explanation is that Samuel fell from one of the chalet’s upper stories, hitting his head on a shed roof on the way down. Or maybe he jumped. Or maybe someone bludgeoned him on an upstairs balcony and then pushed him to his death — and if so, could that someone have been anyone but Sandra? The forensic minutiae are duly intriguing: Blood spatters are closely analyzed, timetables meticulously reconstructed. The suave interplay of Simon Beaufils’ nimble camerawork and Laurent Sénéchal’s jagged editing creates a surface as hypnotic as it is slippery.

But the more significant clues that Triet wants us to ponder are embedded not in the scene of the crime, but in the roiling emotional aftermath of Samuel’s death. What are we to make of not just the intensity but the extreme privacy of Daniel’s grief, from which Sandra tries to extricate him, gently if a bit prematurely? When Sandra breaks down and sobs, “I’m so tired of crying,” should we be suspicious of the fact that is the first time we’ve actually seen her weep — an outpouring of grief that might be calculated for the benefit of her lawyer friend Vincent (Swann Arlaud), who will go on, somewhat reservedly, to defend her in court?

Just because we haven’t seen something, of course, doesn’t mean it didn’t happen — an argument that lawyers use every day, as well as a reminder that all cinematic narrative is an artificial construct. But this line of thinking provokes thornier questions still: Why is it so necessary for us to see Sandra grieve? Why must her relative stoicism in the face of her husband’s death be a sign of her guilt rather than, say, an honestly ambivalent response to the end of a tough, complicated marriage?

Amid all these questions, one undeniable conclusion can be drawn: Sandra Hüller is an extraordinary screen actor. This will hardly come as news to anyone who’s seen her as a hyper-ambitious corporate climber in “Toni Erdmann” or a young woman undergoing a violent exorcism in “Requiem”; in these and other performances, Hüller refuses to feed a stereotype of pliant, palatable femininity. Her blood-chilling performance in the upcoming “The Zone of Interest,” in which she plays a Nazi commandant’s wife, represents her most extreme refusal yet of the audience’s sympathy.

The brilliance of her characterization here is the way it turns the very notion of sympathy on its head. Her Sandra can be vivid and elusive, warm and guarded, calculating and oddly guileless. Whether she’s enjoying a much-needed laugh with Vincent or calmly rebuffing a witness’ testimony, Sandra weaponizes our assumptions against us, including those of how a woman is supposed to behave under extreme or everyday circumstances. It only reinforces her outsider status that the German-born Sandra, with her less-than-fluent command of French, must speak English in court — a pointed detail that resonates all the more profoundly later, when “Anatomy of a Fall” gradually morphs into an autopsy of a marriage.

In due course, Sandra is tried not just for murder, but also for the lesser crimes of being a bad wife, a distant mom and, worst of all, a better artist than her husband. These failings come to light during a furiously written and acted flashback to their final argument, one of those knock-down, drag-out fights in which every possible source of tension and resentment — financial burdens, parenting disagreements, past infidelities — gets dragged to the surface. It becomes the movie’s emotional and thematic centerpiece, so trenchant in its understanding of marital pressure points that it doesn’t sink in until later that the whole sequence, which resembles no other sequence in the movie, is premised on an insidious lie. In “Anatomy of a Fall,” even the rawest of emotional truths turn out to be booby-trapped, and the ever-thin boundaries between life and art are repeatedly violated.

As in her clever 2019 comedy-thriller “Sibyl” (featuring Hüller in a terrific supporting role), Triet is flirting here with questions of literary integrity, artistic theft and the natural compulsion to turn the stuff of personal experience into fiction. To an almost indecently entertaining degree, the movie becomes less grim and more playful as it continues, a family tragedy reverse-engineering itself into a diabolically crafty puzzle. Is it by perverse coincidence or murderous design that Sandra’s ordeal plays like something out of her own fiction? For that matter, is there any significance to the sly meta-flourish of naming Sandra and Samuel after the actors playing them — or the fact that Triet and Harari, the authors of this story, are themselves a real-life couple?

Talk about a literary debate. If there’s anything keeping this infernally twisty story straight, it’s Graner’s haunting performance as young Daniel, a gifted pianist, amateur sleuth and devastated son whose suffering can’t be so easily reduced to a formal device or a red herring. Daniel, with his unseeing yet piercing gaze, turns out to be the conscience of this story, which doesn’t mean that he, his memories or his eventual testimony can be entirely trusted. Innocence, like truth, is an all-too-relative concept in this movie, and one of its lessons is that children carry traces of their parents, including their guilt, in fleeting yet intensely concentrated form.

Certainly, Sandra leaves her own mark on Daniel, for better or worse, by refusing to let either his disability or his grief be the end of his story, and also by imparting to him some unmistakable measure of her own ingenuity and imagination. “Anatomy of a Fall” is a murder mystery, a drama marked by death from its opening scenes, but it is also, in ways both bracing and chilling, about what any of us might do to survive.

'Anatomy of a Fall'

(In French and English with English dialogue)

Rating: R, for some language, sexual references and violent images

Running time: 2 hours, 30 minutes

Playing: Starts Oct. 13 at AMC the Grove 14, Los Angeles; AMC Century City 15

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.