Director Thembi Banks saw her film “Young. Wild. Free.” play at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, this year as part of the Next section, which focuses on adventurous, left-of-center storytelling. A New York native, Banks was previously at Sundance with her 2020 short film “Baldwin Beauty” and also has credits as a writer on “Only Murders in the Building” and directing episodes of “Insecure” and “Brooklyn Nine-Nine.” “Young. Wild. Free.” was co-written by Banks’ former USC classmate Juel Taylor, whose own film “They Cloned Tyrone” recently premiered on Netflix.

Banks’ debut feature follows Brandon (Algee Smith), a teenager in Los Angeles who is just trying to finish high school while grappling with his home life. One night he meets the stylish, spirited Cassidy (Sierra Capri) as she is robbing a convenience store, and the two fall into a whirlwind romance that turns his world upside-down. With a cast that also includes Sanaa Lathan and Mike Epps, the film does not yet have distribution.

Longtime festival programmer John Nein reveals eight tips for applying to Sundance. Plus, seven filmmakers reveal their festival dos and don’ts.

Do you feel like there was something that you learned from going to Sundance and being in Park City?

Being able to be in person there and feel the excitement and the buzz and talk to other filmmakers and hear firsthand how people experience your film, that’s an unmatched experience. And it just further kind of clarified to me that cinema, theatrical cinema, is still something I truly love. As we continue to innovate and move toward different ways of consuming media, that will always be a very, very special experience.

For someone who was applying to Sundance this year and is hoping to go in 2024, would you have a piece of advice for them?

For me, I set out to premiere at Sundance. It was what I spoke, it was what I saw, it was what I felt, it was what I wanted. And I stayed very much on course and on track. I was a person who, like many indie filmmakers in my same shoes, had a very small amount of time to edit, to even get something to Sundance.

When I tell people how much time I had, they can’t believe it. But none of that mattered to me. I knew what I wanted, and I knew I could get there, and I just believed in myself, and I believed that this was for me. And that sounds kind of esoteric and not helpful, but it truly does start there, in you ... I mean, look, we’re in the middle of a strike. That’s one issue, right? So there’s a lot of issues that will be placed in front of you and challenges that will be placed in front of you to make it seem like, maybe not, you might not make it, it might not happen.

Stay steadfast in your belief that you can do it. That’s first and foremost. And then I would just say to make the film that makes you most proud. Not the film that you think will get into Sundance or that you think is a type of Sundance film. “Maybe I’ll edit this scene because this is like a little bit more, you know, Sundance-friendly,” don’t do any of that. Sundance is for unique voices, bold voices, people who tell stories their way. And so if it’s meant to be, the programmers are gonna see that in your film and say, “That person’s gotta be here.” They’re not looking for Sundance films. They’re looking for your film.

What has happened with “Young. Wild. Free.” since the festival? Have you played at other festivals since?

Not yet. We are in the grind right now, but focused on distribution. It has been a very challenging and tricky marketplace for indie films. For films in general, but especially for indie films and the types that come out of Sundance. And so we’re not alone in this journey of trying to find the best place, the best platform and strategy to release the film. We were blessed to get a good amount of offers, but it’s all about figuring out which offer makes the most sense for our film and our particular circumstances. And so that has been a very slow process, in my perspective, ‘cause I’m like, “Can we just get it out there?” But it just has to be that way because of where we are with the state of film.

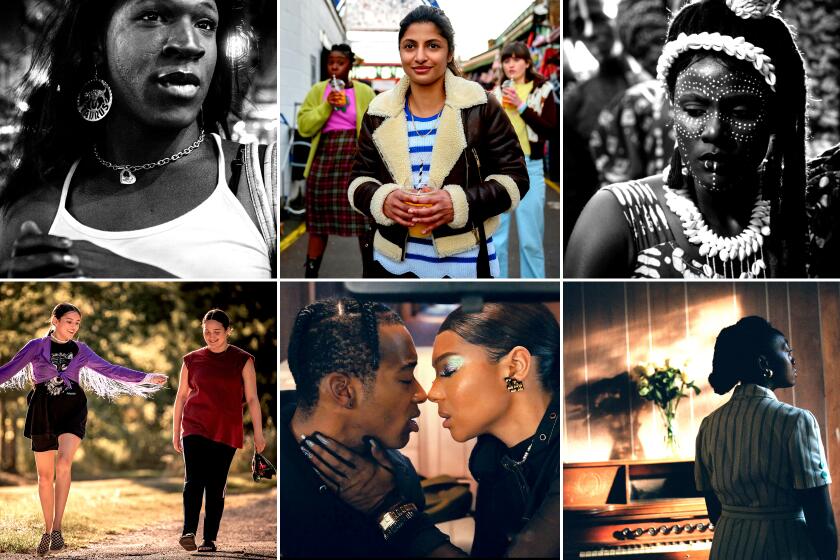

To commemorate next year’s 40th edition of the Sundance Film Festival, we’re spending 12 months looking at the lives of 7 members of this year’s class.

Do you feel like in some ways coming out of the festival, was there some kind of “bounce”?

Yes and no. And the no is not a bad thing. It’s just, I think, a sobering and reality-based kind of perspective. Because I’m such a fan of Sundance and Sundance films and Sundance filmmakers, I’ve consumed and studied and researched so many people and their journeys and processes, and some of my friends have had those journeys. And so I find myself echoing and feeling the same way as those folks. There’s this burst of energy while you’re at the festival and everyone’s excited about you and your film, and they’re talking about it and they’re seeing it, and they’re giving you feedback and you’re doing all this press and everyone’s leaning in, you know, focused on you. And then there’s the moment after, and that moment after could be a couple months, a year or many years, where you realize, “I still have to push forward and keep my story going and keep creating and keep developing myself as a filmmaker and find ways to further define myself out there in the public as far as what my name is attached to.”

I do have this film, and I’m still on that journey of seeing it released and shared with the greater world. But you also realize that this is a very fast-paced, not just industry, but country, right? And so the news cycle, you’ll hear about something and it’ll be all the rage, and then four days later they’ve moved on. That’s kind of how Sundance feels too. And not in a bad way, but just in a way where you have to be reminded that your journey doesn’t stop at Sundance and premiering at Sundance. That’s really just the beginning.

Has it been hard to keep the energy up and keep your momentum going in regards to the movie?

It’s a challenge. You’re dealing with indie films, so you’re dealing with a smaller film, and you don’t have as much money, as much resources, and so you have to be very careful about all the steps that you make and how you spend money and how you spend time, because you wanna make sure that every cent counts. And I’ve been blessed to have really amazing producers behind me. It’s still not like a major motion picture studio. And even in those situations, I’ve heard there’s strategy in place that kind of feels quiet and under the radar as they pull the pieces together. So that’s the part of filmmaking I feel like a lot of people don’t know and aren’t prepared for.

And I’ll say “people” as in me. I wasn’t aware of this time and how it would feel where you’re like, “I made this film. People saw it at Sundance. There was this great reaction and now nothing.” Because we’re trying to be very strategic as far as what other festivals we play at. You can’t just blast it out to every festival known to man. Because you start so big at Sundance, it’s like, “OK, I have to be very particular about where else I screen.” So then you’re like, “OK, I’m figuring out what my next festival will be,” and if the film is not out you’re not necessarily doing press and talking about it and showing it to folks and keeping it top of mind for the greater public, so you’re not necessarily continuing that push to spread it to people where they’re constantly talking about it. You’re in that middle zone there. And so it is very frustrating, because you’re like, “I have something, I wanna show it to the world, but I’ve gotta go through all these steps to do it.”

You mentioned the state of indie film. What has that been like for you to navigate the business side and realize what the environment and even sort of possibilities for the movie can be?

None of the challenges that I’m currently facing in trying to figure out the best place for the film, and knowing that the market has changed and it’s harder to get film period out, has deterred me from wanting to make another one, you know? It’s kind of like having a baby, which I have had. And so it’s like when they say you go through all those labor pains and it’s unbearable and you don’t think you’re gonna make it, and you can’t believe that it feels this hard and impossible. And then you have a baby, and in a few moments you look at that baby and you’re like, “I wanna do this all over again.” Because I’ve completely forgotten the labor pains.

And that is a bit of how it feels to me. No matter how hard it feels right now, or how hard it felt to try to make it. Sharing it with the world and touching people, being at that festival and realizing that scenes and characters and dialogue and visuals touched people, and then also seeing like, “Hey, this started from a spark of an idea, from a word on a page, and I actually did this, I actually created this” — it’s an amazing feeling. And I haven’t made a big commercial film yet, but I feel like it has to feel even more special when it’s the little indie that could, because the small amount of resources, the reason why it could have not gotten made a million times, but it still did.

There are challenging times and the business side is icky, and as a director you often feel a little bit helpless. Because you’re not the producer, you’re not the financier, you’re not the person who has to make these really hard decisions based on money and a lot of other business-related things. You’re just this artist who wants to push it out there. And so you kind of have to sit back and give your opinion and give your perspective. But there are conversations that, because it’s not your money or whatever, are outside your wheelhouse. So you feel a little bit removed from the process in a way where you’re just like, “Ugh.” But it’s part of it.

Especially as a Black female indie filmmaker, do you feel like that kind of makes you a subset of a subset? Are there additional challenges because of that with the movie?

100%. I think being a Black filmmaker and unapologetically having what I feel proud to call a Black film, meaning I have Black cast and I’m telling a uniquely Black story. I think when you get out there and you start to put it out there in the marketplace, you see that there is less value placed on your story. You’ll see other films and in your mind you’re like, “My film has a star in it.” What I feel like is comparable to that film’s star, only they’re white, right? They’re, to me, on the same level, they’ve done the same amount of things. They’ve had the same amount of critical acclaim and praise, but somehow there’s this cloak of excitement and magic put on this film and these actors and this filmmaker as opposed to ours, which a lot of times feels very niche in a bad way, feels very specific in a bad way, feels very limited. And so you start to realize that there’s a smaller section and place and idea as far as what your film will mean to people. And so the money gets smaller, the ability to push it out there gets smaller. The resources they’re willing to put behind it get smaller.

I would imagine it must be such a challenge that at a moment when you want to be out there pushing and really moving forward, the industry at large is sort of like, “Let’s wait and see.” Everything’s slowing down when you wanna be speeding up.

In this particular case, because we have a finished film and we’re not trying to sell a script or pitch an idea, we are able to keep conversations going. But I think in general there’s a slowing down. It’s just like this sludge that it feels like everyone’s moving through. Even with the business that can move, I think there’s this trepidation and this hesitation on making any big sudden moves, spending any money or making any big announcements to slates to a certain degree. But I do think that we are in a great space, because this is a piece of finished content and we all know that there’s been a work stoppage, so there won’t be content. And so I do think that we are in a great space to be able to offer the world something great to watch that can still exist beyond the limits of what the strike entails and what the rules are.

Whether at the festival or since then, has there been anything that’s surprised you?

I am a little bit surprised in conversation how much people are still, five, six months after, talking about it and saying, “You played at Sundance. Wow.”

So you’re just reminded that this was a huge accomplishment. And as the self-deprecating filmmaker who just takes it all in stride, you’re just like, “Yeah, I did.” It’s a small film, and it’s my first time, and we’ll see what happens, if we don’t even know where it’s going. And none of that matters to people. All that matters is that is a milestone that you’ve accomplished. And it’s a big, big deal for folks, and people are really impressed. And no matter what happens with the film, you can always say that you have that and people are really excited and that means something to them.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

After Sundance, but before the strike, were you getting offers? Did you feel like it was generating new work for you?

I’ve definitely, after Sundance and before the strike, had meetings where people had seen my film, and because of that it sparked interest and it started to have them think of me for other projects and other films. And I don’t think it was just because this film is about this and I have a film that’s similar. I think it’s because there’s a trust there. There’s excitement to be able to say, “This Sundance filmmaker could possibly now move on to do this film for my company because we’re honing and cultivating talent that comes from that pool of people.”

When you look back on the experience in Park City, was there an emotional high point for you?

Absolutely. And it’s simple. It’s sitting in the audience as the movie started to play for the first time when it was screening. That moment was amazing because I was sitting next to my cast, sitting right next to Algee, and I had friends and family right in front of me and behind me. And it was all of their first time seeing the film. And to just be sitting there in that moment as they’re experiencing it, it was amazing. It was magical.

Are there any experiences outside your movie that really stick out to you?

One of my favorite things to do as I’ve been going to Sundance is being in this rented house with friends and just laughing and joking and having fun and talking about who’s slipped on the snow today and what fun we had. Just being able to spend time in fellowship with people is just so fun. Outside of the films, outside of the panels, outside of the activations, being able to be in the snow with your friends, people you haven’t seen for a long time, it’s almost sort of like a reunion, it’s almost like a group trip. “Hey, are we gonna Sundance this year?” I think Sundance provides that space for a lot of folks. It’s not about business. It’s not about who’s selling a film or how something played. It’s truly a moment to get away from the hustle and bustle and have a good time.

When someone says, “Oh, that’s so great, you went to Sundance with your movie,” what’s the thing that first flashes in your head?

One of the first things that flashes in my head, to be honest, is me dancing at the Macro party. So Macro was producer of my film. But they historically have had some of the best parties at Sundance. And so I think just a wave of taking selfies with all kinds of people, people who I’m fans of, in those parties — like Tika Sumpter and Megan Goode. Those parties are a huge part of the Sundance experience, if you’re lucky to get in.

One more standout memory was when people were like, “You played at Sundance” is the moment the credits were up on the movie, I turned and hugged Algee, the star of my film. We just like hugged each other. It was really special and emotional.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.