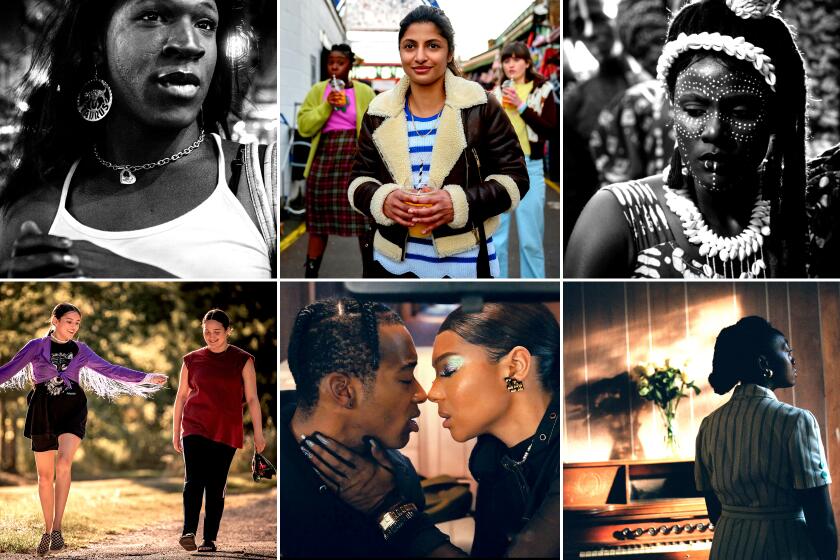

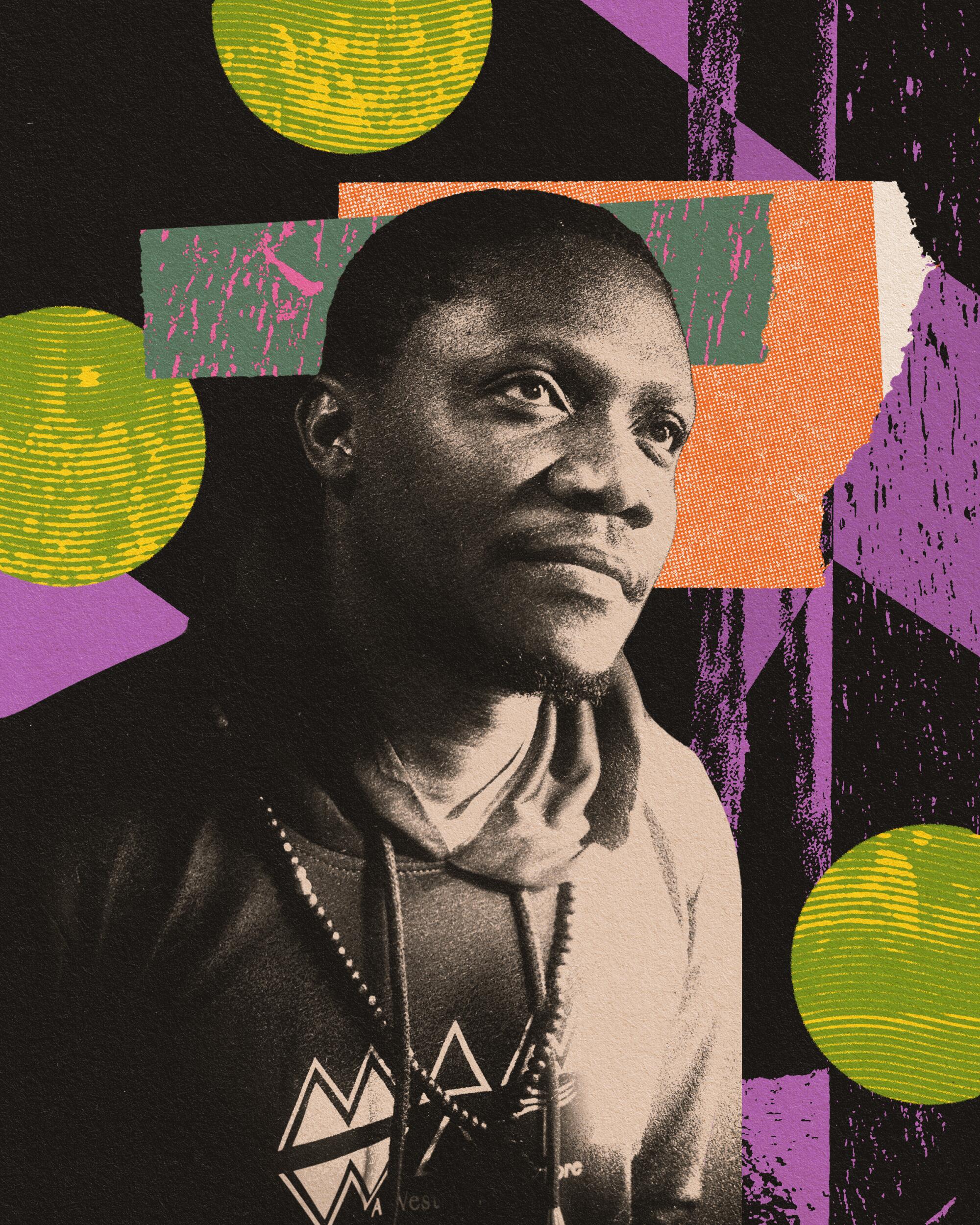

As the first Nigerian-based director to have a feature selected by the Sundance Film Festival, C.J. “Fiery” Obasi had no idea how his movie “Mami Wata” would be received by the crowd in Park City, Utah. A mesmerizing drama set in a fictional West African village whose traditional beliefs in a water spirit called Mami Wata have come under attack, the picture drew strong reviews and earned a jury prize for Lílis Soares’ starkly beautiful black-and-white cinematography. For Obasi, though, as for many of his fellow Sundance filmmakers, the ultimate goal was to land a theatrical release.

What was the emotional high point of Sundance for you?

I had heard the Sundance audience was cultured, having seen all kinds of films from different parts of the world for years and years. But in my mind, no one has ever seen an African film like this before, so I really had no clue what to expect. It was definitely nerve-wracking. So to see it received the way it was received — so massively enthusiastic, all the screenings were pretty much sold out — it was just spectacular.

Sundance was my first time in the States. I don’t know if I have a fair assessment, because all my experience of the United States has been as a filmmaker and through the lens of the industry. Everywhere I go, I’m treated like a king. So I don’t think this is a true reflection of everyone’s regular everyday experience in America.

Were you actively looking for distribution at the festival and meeting with potential buyers?

That had definitely started. We had press and industry screenings before the world premiere, and CAA was handling negotiations for that. I wasn’t in those rooms, but we were getting updates as far as offers and things. My one priority was always that I wanted a distributor that would ensure a theatrical release in North America. Not everyone is willing to take that risk. But [indie distribution company] Dekanalog guaranteed that and showed so much enthusiasm and passion for the film that we just couldn’t see any other way to go. [“Mami Wata” is scheduled to hit select theaters domestically on Sept. 29.]

Longtime festival programmer John Nein reveals eight tips for applying to Sundance. Plus, seven filmmakers reveal their festival dos and don’ts.

If you had to quantify the Sundance “bounce” with one thing that’s happened to you, professionally or personally, what would that be?

After Sundance, I was in L.A. for about four weeks, and that was my “Entourage” experience. It was crazy — I was having minimum three meetings a day, sometimes four or five. CAA had mapped it all out on a professional level, and it was amazing. At the end of the day, I think I belong where I belong. But I had to remind myself I come from a small town and now I’m sitting having a meeting with — I’m not going to mention names — this iconic filmmaker, this iconic producer, these iconic studios, and they are there because of me. It was mind-blowing.

Would you be interested in making films in Hollywood?

I’m certainly not interested in being boxed in. I love being described as a Nigerian filmmaker, because I think that is a unique perspective that I’ll always have and no one can take that away from me. And I can bring that unique point of view to anything else I make and that will translate to a new aesthetic, a new texture. If I decided to make some big sellout film, it would still have a unique perspective. I have 17 projects in my slate right now. Some of those are set in the United States. I never saw myself as a guy who made stuff only from a particular geographical location. That’s just how my mind works.

Last month, you were invited to join the motion picture academy. How did that feel?

Getting the email from the academy was a complete shocker. People started messaging me from all over the world. There was no way I was going to turn that down. Who in their right mind would turn down the chance to see all the Oscar-qualifying movies in the world?

To commemorate next year’s 40th edition of the Sundance Film Festival, we’re spending 12 months looking at the lives of 7 members of this year’s class.

What advice do you have for filmmakers who may now be trying to get their films into a future Sundance?

The thing that I wish we did was to be more careful who we take money from. As indie filmmakers, you’re so eager to get money so you can make the movie that sometimes you forget to cross your Ts and dot your I’s. We ran into a precarious situation with the French funder of the film. At some point, it got so bad that he was threatening the Sundance screening — can you imagine how crazy that is? The first Nigerian-based film to make it into Sundance, and you’re going to try and shut it down for no reason? That just shows you that some people, you might think they are for you but they are not; they are for themselves.

What is your sense of the state of the indie film business right now?

I recognize the struggle of independent film and I wear the indie filmmaker badge with honor. At the same time, I don’t like the fact that it has become this thing where we have to be relegated to the background. Why are the big-budget [filmmakers] the only people who have to be the definition of cinema? I think we are making cinema in its pure form even more than they are and we deserve to be seen. We should fight for it. You shouldn’t just give up and say the big guys have won. Let’s keep pushing. Let’s keep scraping for those screens, and I think we will eventually win because people want to see something meaningful. The aim is to offer experiences that people have never seen before. To me, that is what cinema is all about.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.