Review: A deep-cut masterwork, ‘De Humani Corporis Fabrica’ is already one of 2023’s best movies

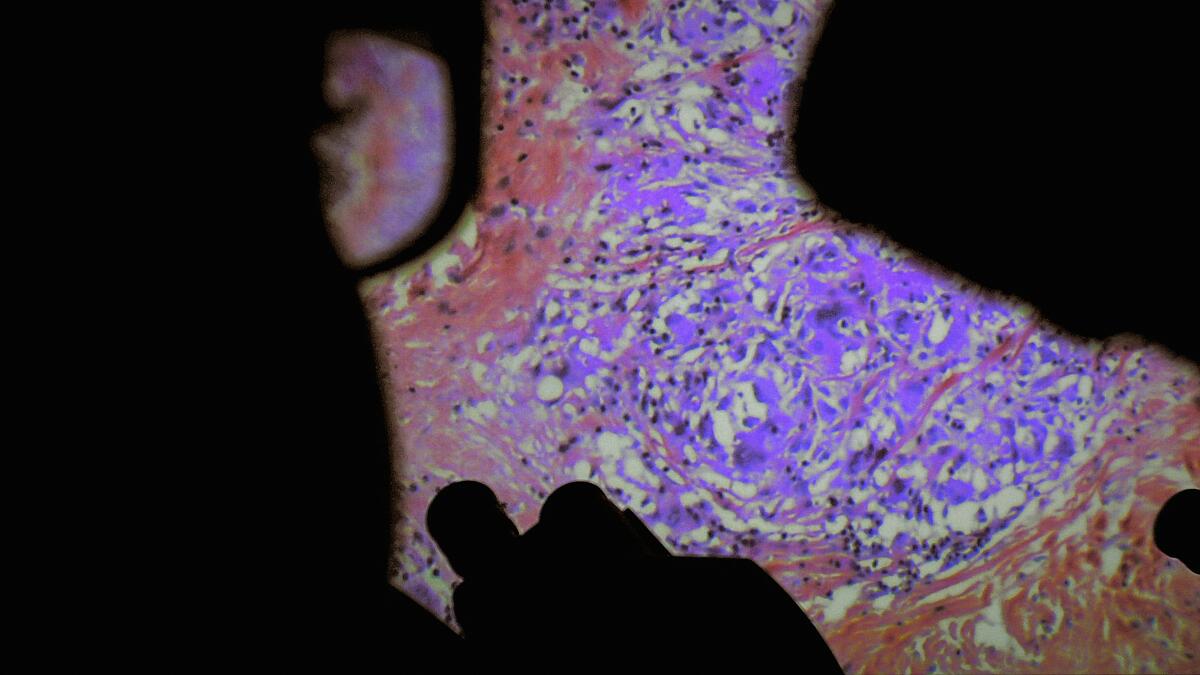

I haven’t gaped at, shuddered through, turned away from or wincingly crossed my legs during a better movie this year than “De Humani Corporis Fabrica.” A headlong plunge into the pulsing caverns and blood-soaked passageways of the human body, this nonfiction shocker — the latest directed by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel (“Leviathan,” “Caniba”) of the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab — stitches a series of surgical procedures into an astonishment of sight and sound, drills and forceps, flesh and blood, life and death. Part Frederick Wiseman-esque medical study, part endoscopic-horror tour de force, it is a thing to be experienced, ideally in a theater — a movie theater, not an operating one, though the filmmakers have a particular genius for blurring the difference.

Their latest work borrows its title from Andreas Vesalius’ 16th century study of human anatomy and owes its existence to custom-built cameras tiny enough to peer into brains and slip through intestines — and, in one dazzlingly reflexive moment, gaze directly into an eyeball undergoing a lens transplant. That particular sequence provides a good early test of your fight-or-flight instincts. Maybe your own eyes will snap shut at the close-up of all those little red veins, the “Clockwork Orange”-style speculum and the scrubbing, massaging motions of a probe against the cornea, followed by the sudden pull-back of the camera to confirm that all this violence is, in fact, being done to the highly sensitive (if temporarily numbed) organ of a fully conscious human being.

Then again, perhaps you’ll be mesmerized, even through splayed fingers, by the sight of experts at work, and also by the strange, otherworldly images their work generates. There’s the fiery red-orange glow of the iris, the sudden onrush of liquid that bathes and (one hopes) soothes, and finally that last little tug of the forceps as — ta-da! — the new lens snaps into place with satisfying, ship-in-a-bottle precision. It’s amazing what you the spectator can withstand, and what the human body can withstand too. This movie, which the Los Angeles Film Critics Assn. recently honored with its Douglas Edwards Experimental Film Award, may be the definition of “not for the squeamish.” And yet this champion squeamer emerged from it (twice!) with a newfound awe for the resilience of the flesh and a deeper-than-ever respect for the doctors who so fearlessly carve into it.

Shot over more than six years across eight French hospitals (chiefly the Beaujon Hospital and the Bichat-Claude Bernard Hospital, both located in Paris), “De Humani Corporis Fabrica” was made in close collaboration with patients and medical professionals, many of whom we see in its more conventionally shot footage of rooms and operating tables. Castaing-Taylor and Paravel layer this material throughout, acclimating us to the routine rhythms of hospital life before zipping us, with a whoosh, to the next stop on their surgical mystery tour. It’s often a relief when they zip back out again; uncompromising avant-gardists though they may be, the filmmakers do want to keep you in your seat. They’re canny enough entertainers to dole out their spectacle with a steady hand.

The zooms in and out also establish a crucial, contrapuntal rhythm between doctors and patients, and also between the physical and the abstract. Easy as it is to get lost in all that jaw-dropping, cavity-probing imagery, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel never let us detach from the flesh-and-blood reality of what we’re looking at. Many of the operations are accompanied by surgeons’ and nurses’ disembodied voices, sometimes making banal chitchat (two discuss the cost of rent in Clichy) and sometimes contextualizing the imagery you’re seeing. And it isn’t always clear what you’re seeing: A C-section is gruesomely self-explanatory; the burnt-looking layers of a just-removed tumor, not so much. I’m still not sure what’s going on with all that feathery membranous material around a patient’s pituitary gland, or the precise purpose of the tiny instrument that strips, chisels and fires away its tubular surroundings, like a combination micro lawn mower and welding machine.

The technology is incredibly sophisticated. But “De Humani Corporis Fabrica” reminds us that, for all the ingenuity of those devices, there are always human hands operating them, and those hands are not always at their best or fully in control of what they’re doing. One especially nerve-wracking sequence finds a surgeon brazenly attempting a Retzius-sparing prostatectomy for the first time (“I watched the master class by that Indian guy” he says, none too encouragingly).

Even when things go relatively well — when blood doesn’t leak, when instruments don’t malfunction — the movie lingers meaningfully on its medical professionals and their everyday exasperation and exhaustion. We hear them curse and complain about grueling schedules and incompetent colleagues, about rampant understaffing and a workload as stressful as it is unrelenting. “I’m a robot. … I’m on the verge of a heart attack,” a doctor complains, right after tossing off a routine yet nightmarish-looking procedure involving a penis, a urethral drill and something ominously referred to as “the Kalashnikov setting.”

There’s a telling irony in the idea that certain highly skilled medical professionals might not be especially good at taking care of themselves. In these moments, “De Humani Corporis Fabrica” becomes not just tense and flabbergasting but also deeply moving; it gets at the idea of a kind of spiritual and corporeal transference, the knowledge that healing other people’s bodies invariably exacts a toll on one’s own. That’s no less true in the many scenes of nonsurgical care: in the hallway where a worker tries to coax a patient with dementia back into his room, or in the ICU where a nurse delivers a long and wrenching monologue about the horrors she witnesses on a daily basis. It’s one of this extraordinary movie’s least graphic scenes and one of its most powerful, a reminder of how fragile and precious are the bonds that bind the body to the soul, the living and the dead.

‘De Humani Corporis Fabrica’

In French with English subtitles

Not rated

Running time: 1 hour, 58 minutes

Playing: Starts April 28 at Laemmle Glendale

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.