Review: The powerful ‘Filmmakers for the Prosecution’ shows how cinema held Nazi war criminals to account

In 1945, as Europe smoldered and the world waited for justice, the American brothers and military veterans Budd and Stuart Schulberg embarked on the most difficult and important assignment of their lives. Their mission, handed to them by the Office of Strategic Services, was to track down filmed evidence of German war atrocities, which would be used in the prosecution of Nazi defendants at the Nuremberg trials. Both brothers would go on to careers in film and television — Budd as the Oscar-winning screenwriter of “On the Waterfront,” Stuart as a producer of news documentaries — but not until after gaining a rare firsthand understanding of cinema’s potential as an indictment of evil and an instrument of justice.

How the Schulbergs painstakingly gathered and compiled enough footage on a tight three-month deadline is one of several stories amassed in the engrossing new documentary “Filmmakers for the Prosecution.” Directed by Jean-Christophe Klotz and adapted from a monograph by Stuart’s daughter, Sandra Schulberg, the movie is, like so many Nuremberg accounts, an alternately thrilling and chastening portrait of accountability in action. But it is also, as its title suggests, a thoughtful appraisal of the moral properties of the moving image. The guilty verdicts at Nuremberg were achieved, it reminds us, by way of a mountain of shocking and irrefutable visual evidence, filmed by the Nazis themselves and brilliantly turned against them in a court of law.

For your safety

The Times is committed to reviewing theatrical film releases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because moviegoing carries risks during this time, we remind readers to follow health and safety guidelines as outlined by the CDC and local health officials.

Animated in its early stages by old TV interviews with Budd Schulberg (who died in 2009), the movie plays initially as a tribute to can-do American spirit. The brothers received their orders from none other than the director John Ford, then head of the OSS field photographic unit and a major driver of the Hollywood war effort. Budd attributes some of their footage-finding success to a fateful meeting with a Red Army captain who himself turned out to be a Ford super-fan and scholar. (That fleeting sense of kinship between American and Soviet veterans finds a sad counter-echo in the film’s later passages, which detail how a promising spirit of postwar international collaboration fell apart with the onset of the Cold War.)

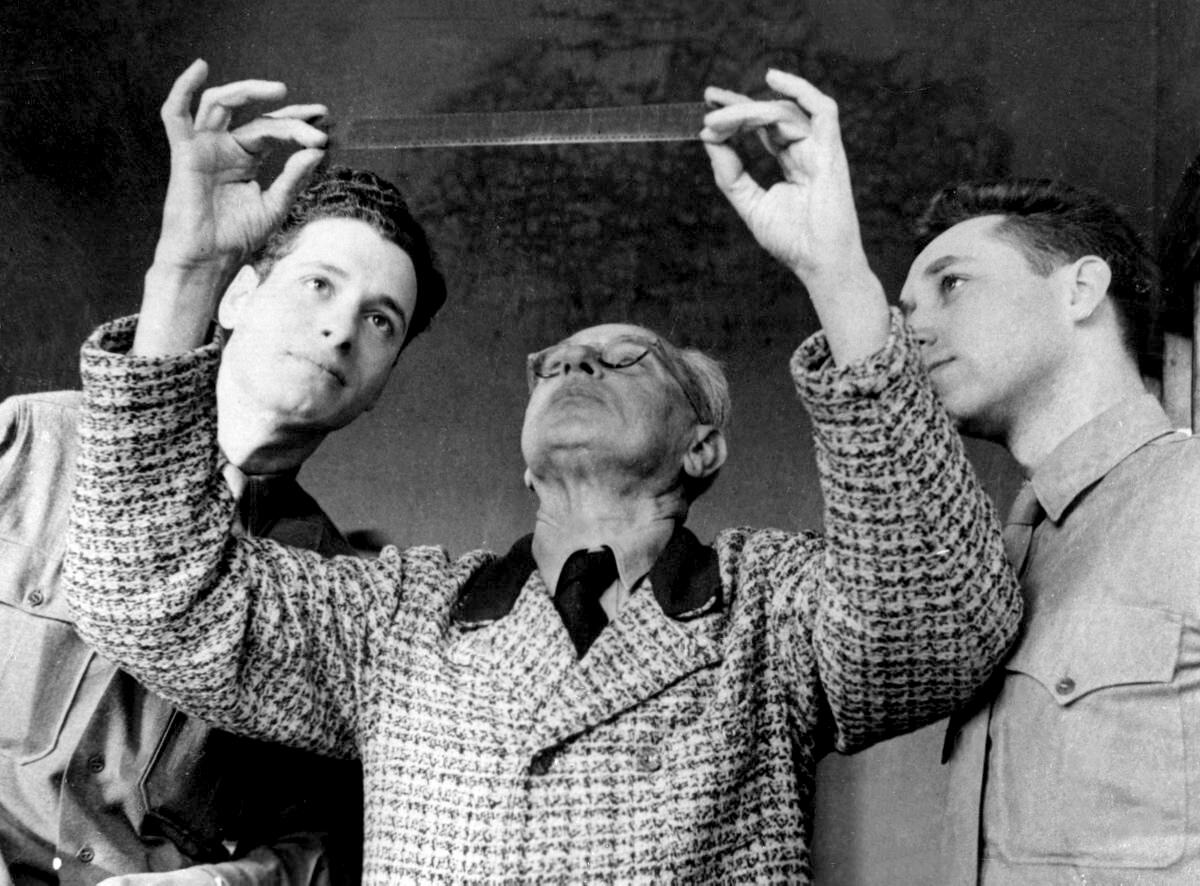

Klotz absorbingly details the brothers’ race to salvage the incriminating film caches before the Nazis could destroy them — a race that led to the arrest and detainment of several Third Reich propagandists, including Leni Riefenstahl, and at one point brought the Schulbergs into the depths of a German salt mine. The footage itself, generously sampled across the documentary’s 58-minute running time, drew on everything from pogroms, book burnings and Hitler rallies to the concentration camps themselves. Chances are you’ve seen some of these images before, given how much of the visual record of the Holocaust can be traced back to the images — the primary sources — that the Schulbergs excavated and edited.

The particular power of “Filmmakers for the Prosecution” is that it suggests what it must have been like to behold such images, in all their starkness and horror, for the first time. Its most gripping passages transport us to the Palace of Justice at Nuremberg as the trials get under way in September 1945, and the logistics of assembling and projecting the footage come into play. The details and negotiations are utterly fascinating: the highly meaningful decision to give the cinema screen pride of place in the courtroom, where the judge typically sits; the discreet positioning of cameras and light sources to document as much of the trial as possible; and the facial reactions of the defendants, among them infamous Nazi leaders like Hermann Göring and Rudolf Hess, upon being confronted with incontestable evidence of their crimes.

The significance of filmmaking at Nuremberg was at least twofold: There was the preexisting Nazi footage that had been compiled, and there were also the films — one American, one Soviet — that were shot during the trial itself. “Filmmakers for the Prosecution” details how the American project, directed by Stuart Schulberg and titled “Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today,” was completed in 1948 but went unreleased for years. As political winds shifted and the Berlin Blockade began, a documentary about one of the last great examples of U.S.-Soviet cooperation in action was determined not to be in the American public’s best interests.

The long-overdue 2010 release of “Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today,” following a restoration effort spearheaded by Sandra Schulberg, went some distance toward correcting that oversight. “Filmmakers for the Prosecution,” opening this weekend in Los Angeles, achieves its own highly specific resonance. Arriving at a moment when images of atrocities have become a matter of everyday institutional record and public consumption, it laments the barbarism we see in these images — and implicitly asks what it would take for them to shock and shame us anew.

‘Filmmakers for the Prosecution’

In English, French and German dialogue with English subtitles

Not rated

Running time: 58 minutes

Playing: Lumiere Music Hall, Beverly Hills

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.