How to watch every Best Picture winner from 1980 through 1989

First-time director Robert Redford set the bar for the decade with the family drama “Ordinary People” (1980), for which he also won the Oscar for directing.

Richard Attenborough — another actor-turned director — also won the directing award for a best picture winner “Gandhi” (1982), as did James L. Brooks (“Terms of Endearment,” 1983); Milos Forman (“Amadeus,” 1984); Sydney Pollack (“Out of Africa,” 1985); Oliver Stone (“Platoon,” 1986); Bernardo Bertolucci (“The Last Emperor,” 1987) and Barry Levinson (“Rain Man,” 1988).

How to watch Oscar Best Picture winners through the decades

Intro and 1920s | 1930s | 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | 2020s (and 2020 nominees)

1980: ‘Ordinary People’

53rd Academy Awards — April 1981

Rating: R.

Running time: 2 hours 4 minutes.

Streaming: Paramount+: Included | Prime Video: Included | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

Robert Redford makes his debut as a nonacting director in the strongly emotional and beautifully written and performed family drama, “Ordinary People.”

Like every actor-turned-director I can think of from Olivier forward, Redford is at his best working with his fellow actors to evoke performances of sensitivity and believability over a wide emotional range. “Ordinary People” is entirely a film of performance, which is obviously what attracted Redford to the novel in galley form, well before it had been established as a commercial success.

Donald Sutherland is a very prosperous Chicago tax attorney living well in the posh North Shore suburb of Lake Forest. His wife is Mary Tyler Moore, who at a very misleading first glance is simply a more mature version of the effervescent helpmate on the Dick Van Dyke show. They have had two teenaged sons, but a few months before the events of the film the elder son drowned during a sudden storm on a lake. The younger son, tensely and sympathetically played by Timothy Hutton (the son of the late Jim Hutton), has attempted suicide, been hospitalized, and, as we meet him, is home again, shakily trying to resume his place in the ordinary world.

The suspense, of course, is whether the boy, in touch with no one, finding comfort from no one, will again try to destroy himself. The tone of the film allows no easy assurance that things will work out. Life is not necessarily benign. (Read more) — Charles Champlin

1981: ‘Chariots of Fire’

54th Academy Awards — April 1982

Rating: PG.

Running time: 2 hours 3 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

“Chariots of Fire” has sports as its backbone and passion as its fueling emotion. It traces the parallel lives of two athletes — or, more correctly, two extraordinary men to whom running was necessary part of life — who became part of the remarkable British track and field team at the 1924 Olympics.

They were the dark and the light; the fiercely competitive Harold Abrahams, to whom running as a weapon against the snobbery and anti-semitism he encountered at Caius College, Cambridge (and before), and Eric Liddell, the son of a Scottish missionary, whose will to run came from a passionate spirituality.

Steadily, a mite awkwardly at first, the twin stories build. The awkwardness comes from a break at the opening. It begins at a funeral in 1978, then shifts back in memory to 1924, at the edge of a misty beach in France where, like horses running in the sea out of pure joy, the British Olympic runners are running barefooted, each in his distinctive style.

And under the scene, the first hint that this is something other than an old-fashion film. As the noble piano theme is stated there are nervous electronic sounds which catch the runners’ tension and transmit it. The work of Vangelis Papathanassiou, who uses only his first name in his composing and conducting, this is an original and breathtaking score. (Read more) — Sheila Benson

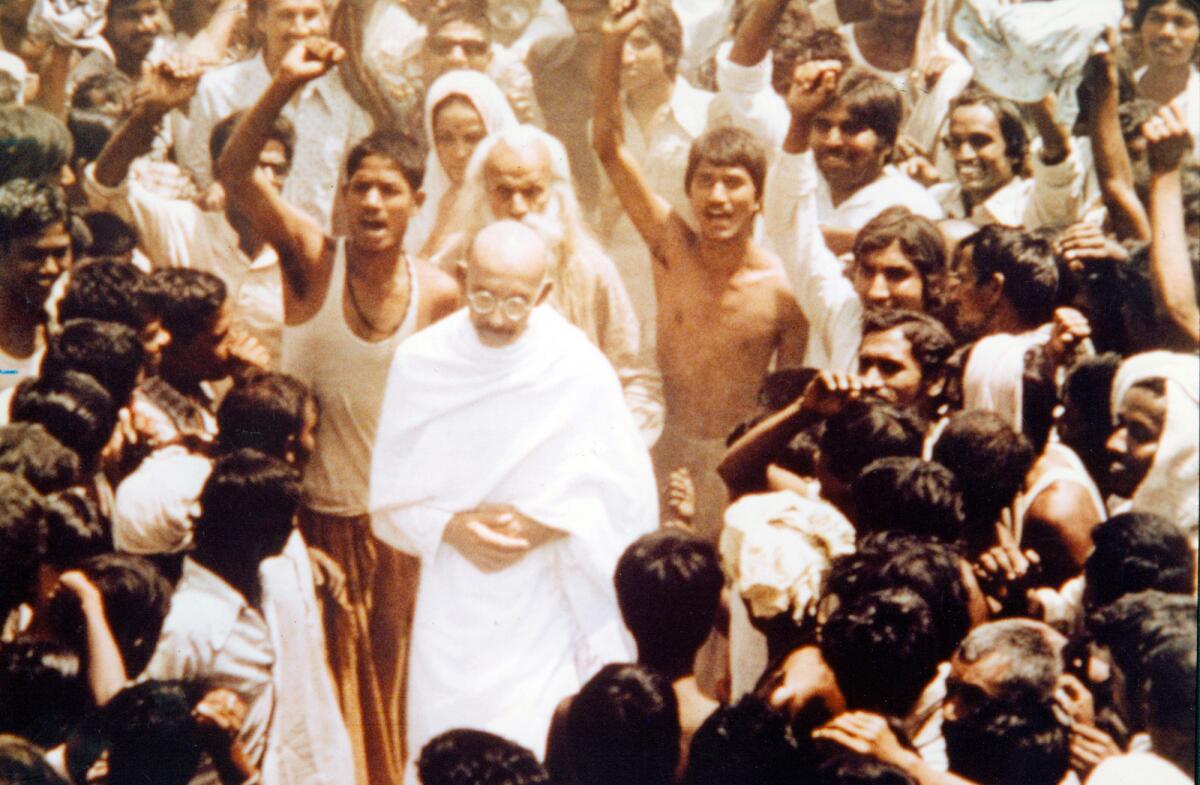

1982: ‘Gandhi’

55th Academy Awards — April 1983

Rating: PG.

Running time: 3 hours 11 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

The way in which director Richard Attenborough illustrates the motivating incident of Mohandas Gandhi’s life in “Gandhi”tells us a lot about the film to come.

Summarily thrown out of a first-class, whites-only railway carriage onto a dark, South African train station pavement, the enraged 23-year-old Indian attorney looks around him. The Maritzberg station is almost deserted and a chill wind blows. An Indian couple watches him from across the tracks, then moves away silently. His isolation is heightened by a high-angle shot.

It was the night that Gandhi always referred to as the moment his path was set, but we cannot read his emotions. They must have included outrage, fury, a scalding humiliation, possibly even thoughts of recrimination, but they remain private until they are intellectualized in talk the next day.

Attenborough and his screenwriter, American-born John Briley, warn us in a preface that they have selectively chosen incidents from Gandhi’s life, being faithful in spirit to the record and trying to find their way to the heart of the man.

The body of the film with its magnificent central performance by Royal Shakespeare Company member Ben Kingsley does everything it can to make us understand India’s loss as if it were our own (Read more) — Sheila Benson

1983: ‘Terms of Endearment’

56th Academy Awards — April 1984

Rating: PG.

Running time: 2 hours 12 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

Life is what happens while you’re making other plans,” John Lennon wrote, and in “Terms of Endearment” , it does just that. In this pungent and beautifully observed film, the most completely satisfying of this and many another year, life is fascinating, tender, hilarious, catastrophic, healing, warm and, in the main, a faintly absurd predicament in which to find oneself.

We have a front-row seat for one of the damnedest, cut-on-the-bias mother and daughter relationships to warm a screen. We pick it up at intervals, from the moment the capricious and determined Aurora Greenway (Shirley MacLaine) hovers over her newborn Emma through the high and low points of their next 30-odd years. The essence of their relationship is summed up in two looks that pass between mother and daughter, one at the beginning, one at the end of the picture.

But catch her motherly advice the night before gangly, teen-age Emma (Debra Winger) is going to be married to Flap Horton (Jeff Daniels), a boy with a comic/handsome face and the soul of a perpetual graduate student.

In one stroke, writer/director/producer James L. Brooks sets the tone for his extraordinary picture, which is both faithful to and bravely inventive with Larry McMurtry’s literate and singular novel. The film bristles with the best dialogue in memory and with effortless transitions over its broad period of time. It deals with the absolute real stuff of life from new and sometimes dazzling angles. And each time you think you know where a character or a situation will take you, it pulls the rug out from under you. (Read more) — Sheila Benson

1984: ‘Amadeus’

57th Academy Awards — April 1985

Rating: PG (2002 Director’s cut reissue: Rated R for brief nudity).

Running time: 3 hours.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

To be able to perceive genius, to luxuriate in its example, all the while knowing that one’s own work would have to strain to reach mediocrity is a pretty good working definition of hell on earth.

In “Amadeus” Peter Shaffer’s play, which he and director Milos Forman have turned into an enthralling film, the genius is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the “mediocrity” is Antonio Salieri — reigning success of the court of Emperor Joseph II of Austria in the late 18th Century — and the confrontation between the two is fatal.

The story is told in the framework of a memory by the very old Salieri (F. Murray Abraham), consigned to a madhouse after his attempted suicide. He has outlived Mozart (Tom Hulce) by 32 years, and watched his own compositions wither in popularity during that time. (Read more) — Sheila Benson

Tom Hulce decided he had enough of the acting life.

1985: ‘Out of Africa’

58th Academy Awards — April 1986

Rating: PG.

Running time: 2 hours, 31 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

We are starving just now for civilized films, for the play of intelligent minds in movies about something. In that frame of mind, “Out of Africa” — with its intense civility, its irreproachable landscapes, the tensions of its faintly doomed love story, which is not about love, really, but about possession, and its twin superstars — seems to be just the thing for famished culture mavens at Christmastime.

Unfortunately, and through no fault of Meryl Streep, there doesn’t seem to be enough electricity generated out there in Africa to power a love story 2 1/2 hours long.

Sydney Pollack’s lush production takes us to unspoiled Kenya in 1914 with the aristocratic Karen Dinesen (Meryl Streep), a Dane, a storyteller of the first order, and enough of a snob to marry for a title. Actually, her marriage there in Nairobi only hours after she has arrived is not to the man she loves — who spurned her — but to his twin, Bror Blixen (Klaus Maria Brandauer, full of quicksilver charm, and who, if you look quickly, plays both brothers.)

Clearly, this is not going to be an evening with the Bickersons. Luedtke has been equally deft in sketching in the ineffable homesickness of these Brits abroad, as one of them feasts on Karen’s perfume, thinking for a moment it’s one he remembers rather well. Ah. No. Very nice, but not the same. (Read more) — Sheila Benson

‘What business had I ever to set my heart on Africa?’ author Isak Dinesen once wrote. But then, what business have any of us to set our hearts on a place?

1986: ‘Platoon’

59th Academy Awards — April 1987

Rating: R.

Running time: Running time: 1 hour, 51 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

In “Platoon” writer-director Oliver Stone drops us as he drops his autobiographical 19-year-old, Chris Taylor (Charlie Sheen), into life with the 25th Infantry in Vietnam. It’s a war where there seems to be no master plan, no big picture and no advances. There is only terror, bone-deep exhaustion, nighttime patrols and the humid jungle, crawling with snakes, insects and the silent Viet Cong.

This is movie-making with a zealot’s fervor. Stone, a college dropout, Vietnam infantryman himself with a Bronze Star for valor and a Purple Heart, clearly wants us to understand what fighting in that war was like. He succeeds with an immediacy that is frightening. War movies of the past, even the greatest ones, seem like crane shots by comparison; “Platoon” is at ground zero.

By opening with no preamble, Stone put us into his soldiers’ boots: An aircraft cargo bay yawns wide to discharge “the cherries,” these achingly young soldiers, into the swirling, sulfurous dust of a Vietnam air base in 1967. Rounded up from map-dot towns like Pork Bend, Utah, and Pulaski, Tenn., rushed through training and shipped overseas, these recruits exchange incredulous stares with the war’s old men at the base, 22- and 24-year-olds who look 40 years older. And they stare at the black rubber body bags being matter-of-factly flopped back onto their cargo planes.

Then they — and we — are in the jungle, where everything cuts or stings or goes off, where sleep is in two-hour shifts and there’s never enough of it, and where the death of a “cherry” isn’t the same as the death of a long-timer, because he hasn’t yet paid his dues.

The platoon’s two rival sergeants — and its twin moral poles — are established: Tom Berenger, his face a road map of scars, as Barnes, and Willem Dafoe as Elias. Both men are superb fighters and consummate leaders but Barnes’ style is to be the stern father, Elias’ the compassionate mother. (Read more) — Sheila Benson

A year after “Platoon” swamped the Academy Awards, some of the lesser-known actors who sludged through that Oscar-laden war zone have prospered, while others are still scuffling.

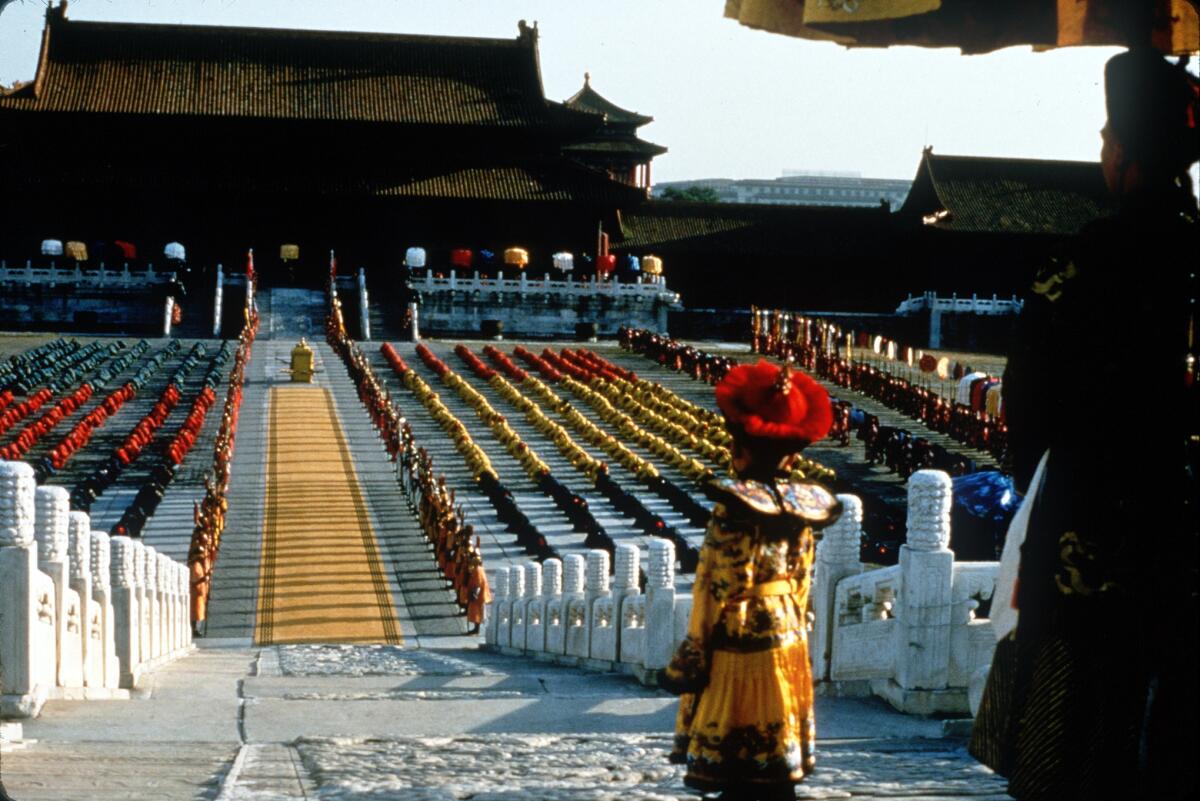

1987: ‘The Last Emperor’

60th Academy Awards — April 1988

Rating: PG-13.

Running time: 2 hours, 45 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

In 1908, on the whim of the Empress Dowager dying under her cracking whitewash makeup, a beguiling 3-year-old is torn away from his mother in the dark of night and taken, with his wet nurse, to China’s most astonishing palace — the 9,999-room Forbidden City. There, robed in imperial yellow and placed on a Dragon Throne, tiny Pu Yi becomes 10th Quing Emperor, ruler of nearly half the world’s people.

And so begins the life of “The Last Emperor” as coolly lavish an epic as we may ever see. Giving free rein to the cinema’s most voluptuous troika of imagists — director Bernardo Bertolucci (“1900,” “Last Tango in Paris”), production designer Ferdinando Scarfiotti (“The Conformist,” “American Gigolo,” “Scarface”) and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (“Reds,” “Apocalypse Now”) — has resulted in an intoxicating visual rush. (Read more) — Sheila Benson

1988: ‘Rain Man’

61st Academy Awards — April 1989

Rating: R.

Running time: 2 hour, 20 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy | HBO Max: Included

Although it roams across expanses of America, “Rain Man” is a small, mostly interior journey: the awakening of two walled-off souls. Actually, it’s more like the greening of one soul, Tom Cruise’s Charlie Babbitt, and the nudging of another, Dustin Hoffman’s Raymond Babbitt, Charlie’s older brother, whose autistic condition makes “awakening” far too dramatic a word.

Because we’ve had dozens of buddy films about journeys of discovery, we can plot the scenario like a road map: The special qualities of one will work on the other to change him, or perhaps both of them, and probably not for the worst.

In that respect “Rain Man” will disappoint no one. Though it seems impossible that wheeler-dealer Charlie, Mr. Sharper Image incarnate, will ever put anyone ahead of Numero Uno, there’s a little room for hope by the movie’s end. And as far as the unelastic Raymond can stretch, he does, as he moves from lifelong institutionalization to a week of freedom on the road.

It’s greed on Charlie’s part that has brought the two together. Notified that his father has died, he goes back to Cincinnati to lay claim to his estranged parent’s estate, some $3 million, only to learn that it’s been left in trust to an older brother he never knew he had: Raymond. The next shock is learning that Raymond is autistic and institutionalized. The third shock comes when Charlie virtually kidnaps Raymond and sets out for Los Angeles, hoping to use Raymond’s presence as leverage to work a deal for at least part of the money. (Read more) — Sheila Benson

1989: ’Driving Miss Daisy’

62nd Academy Awards — April 1990

Rating: PG.

Running time: 99 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

Morgan Freeman’s performances this year in “Lean on Me,” “Johnny Handsome,” and, now, “Driving Miss Daisy,” have been among the best reasons to go to the movies. (He’s also in “Glory,” the Civil War drama opening tomorrow.) Freeman has an infuriating habit of being extraordinary even in mediocre movies; his presence, alas, makes them must-sees.

“Driving Miss Daisy,” directed by Bruce Beresford and adapted by Alfred Uhry from his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1987 play, isn’t mediocre. It’s musty and schematic, though, with a measured pace that’s meant to incur our respect. This is “quality” theater transferred relatively intact to the screen.

The central relationship is between Daisy Werthan (Jessica Tandy), a cranky Atlanta widow and Hoke (Freeman), the chauffeur hired by Daisy’s son Boolie (Dan Aykroyd) to keep her from plowing her brand-new ’48 Packard into the neighbor’s flower beds. The film takes us through 25 years of winsome acrimony between these two. Their mellowing relationship is meant to mirror the growth of civil rights in the South. Daisy is Jewish, and so the movie is structured as a tale of two outcasts bonded by their stubborn pride. (Read more) — Peter Rainer

How to watch Oscar Best Picture winners through the decades

Intro and 1920s | 1930s | 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | 2020s (and 2020 nominees)

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.