Her new thriller takes on the male ego. She hopes it starts fights in the parking lot

One emerging sub-theme at this year’s Sundance Film Festival is piercing examinations of the dynamics between men and women. Susanna Fogel’s “Cat Person” is an adaptation of Kristen Roupenian’s New Yorker short story on differing perspectives on a date gone wrong. Nicole Newnham’s documentary “The Disappearance of Shere Hite” looks at the responses to the noted sex researcher and author.

“Fair Play,” premiering Friday as part of the festival’s U.S. dramatic competition, is the feature debut for writer-director Chloe Domont, told in a sleek, seductive style that keeps audiences off-balance, at once drawn in, turned on and disoriented. The film, from MRC and Rian Johnson and Ram Bergman’s T-Street, stars Phoebe Dynevor (“Bridgerton”) and Alden Ehrenreich (“Solo: A Star Wars Story,” “Rules Don’t Apply”) as Emily and Luke, both employees at a highly competitive New York financial firm. When Emily gets a promotion that Luke thought was going to be his, their relationship begins to unravel. As Emily comes into herself in her new position, Luke feels he is being left behind and they both find themselves pushed to the edges of what they can handle.

For the record:

6:40 p.m. Jan. 20, 2023A previous version of this story referred to Phoebe Dynevor’s character as Alice. Her name is Emily.

Having grown up in Studio City, Domont went to New York City for film school and began her career there before moving back to Los Angeles. Her short films “Haze” and “All Good Things” played numerous festivals and she also wrote and directed on the series “Ballers” and directed episodes of “Billions.”

Domont had begun writing “Fair Play” before she got the job working on “Billions,” which is likewise set in New York’s finance industry. She had long had an interest in that world from movies such as “Wall Street” and “Working Girl” and found it to be a suitable setting for her own story.

“I was interested in something that is high stakes,” Domont said. “I was interested in how the toxicity of a work environment feeds into the toxicity of a relationship and vice versa.”

She got on a video call just a few days before the Sundance world premiere of “Fair Play” to talk about the film.

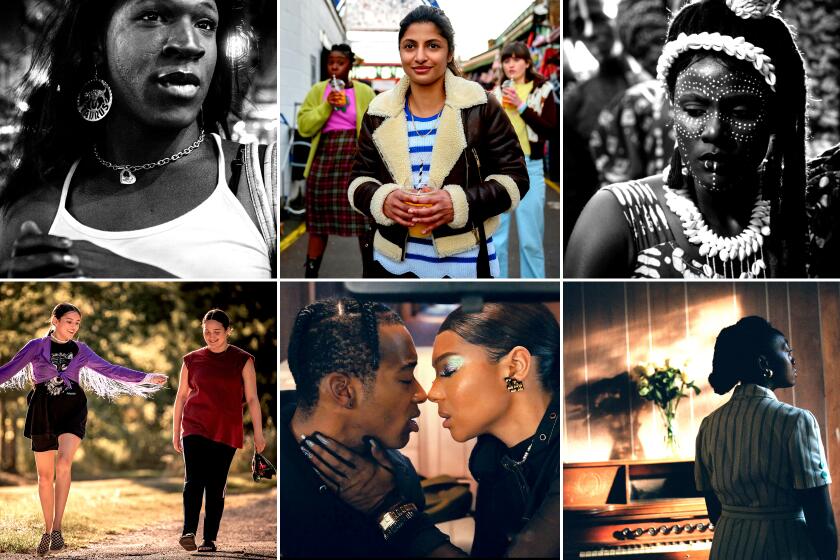

The first in-person Sundance since 2020 is about to begin. Our critic has some early recommendations, including ‘The Eternal Memory’ and ‘Mami Wata.’

Considering that the finance world is so often seen as this hyper-masculine environment, what made you want to use that setting to explore the dynamics of male-female relationships?

Well, first of all #MeToo never hit the finance world. Those guys were never held accountable for anything, because money and power, at that level, you can’t touch those people. And women are forced to play ugly to survive in that kind of world and with those kinds of men. What they have to sacrifice of themselves to make their way up in that world, that was important for the story that I wanted to tell.

Was this a challenge to cast? How did you come to Phoebe and to Alden?

Emily is a rising star in the world of finance, and I thought that it would be exciting to cast a rising star. And Phoebe coming off of “Bridgerton” had that buzz to her. But what was really exciting is that she hadn’t done anything like this. And that excites me about casting. I think everyone that we’ve cast in this film had never done anything like this before.

In terms of Phoebe’s qualities, she is so present, she is so tuned in to the moment, that is really her greatest strength. She is really listening, she is really reacting. That’s a key factor with any great performance. There’s also a warmth to her and a vulnerability, but also a fierceness and, most importantly, an untapped fury that I wanted to pull out of her.

But I always knew that the character of Luke, it was going to take a really confident man to play that level of insecurity. Because a male actor who is insecure themselves might be insecure about going to those insecure places. So I knew that whoever I cast had to be really confident, had to be comfortable in their own skin, with who they are. And that was Alden. He just dove into those places headfirst without question.

As the movie plays out, the point of view of the story really fractures, the perspective seems to shift, so that it becomes less certain for a viewer who you’re with. What was it that made you want to tell the story in that way?

I’m not interested in telling stories that are black-and-white, where you’re definitely with some character and you’re definitely against another character. I also just don’t feel like that’s realistic. Luke, in terms of his character, there’s so much he’s struggling with. He loves Emily because of her ambition and her drive and her intelligence, but he also can’t help but feel threatened by the very same things that he loves about her. And that doesn’t make him a bad guy.

And that was important for me to lean into: He’s not a bad guy. He’s struggling with something that I don’t think is really his fault. It’s the way he was raised, the way he was conditioned, the way he was wired. ... I think that this is a systemic societal problem. For the most part, society still only puts out one image of masculinity and one image of success for straight men. And if they don’t fit into that, they’re made to feel like failures.

I started really writing from a place of anger. But the more I developed it, the more I got deeper into his character, the more I realized it was a tragedy on both sides. ... Luke chooses a destructive path because he can’t see any other way out of his pain.

The last handful of scenes in particular become very complex regarding the dynamic of their relationship, who’s at fault, who’s pushing and triggering what happens between them. Was that difficult for you to modulate, to keep that ambiguity, whether in the writing or directing Phoebe and Alden?

[The characters] are doing the best that they can. They’re both in a lot of pain, and they’re reacting to that pain that neither of them know how to deal with, and worse than that they don’t know how to talk about it. And so they start to work through it in all the wrong ways. In many ways this film shows the repercussions of what happens when these issues fall silent.

No one person is going to come out of the movie feeling the same way about the characters at any given moment. It’s going to be so specific to who they are in their own personal experiences. Some people will come out and they’ll be with her the second half of the movie; some people will come out and they’ll be with him. A lot of people will come out and they’ll be back and forth, and I think it’s just really specific to who they are. For me it was trying to just lean into the empathy all the time.

He’s just not equipped to deal with his pain and with an outcome that he doesn’t know. And same thing with her. I think the movie really shows the problems when women walk on eggshells trying to protect the male ego. Neither of them really know how to work through it in healthy ways. And that’s what’s human about it. That’s what was exciting to me about it. That’s what escalates the drama and the conflict.

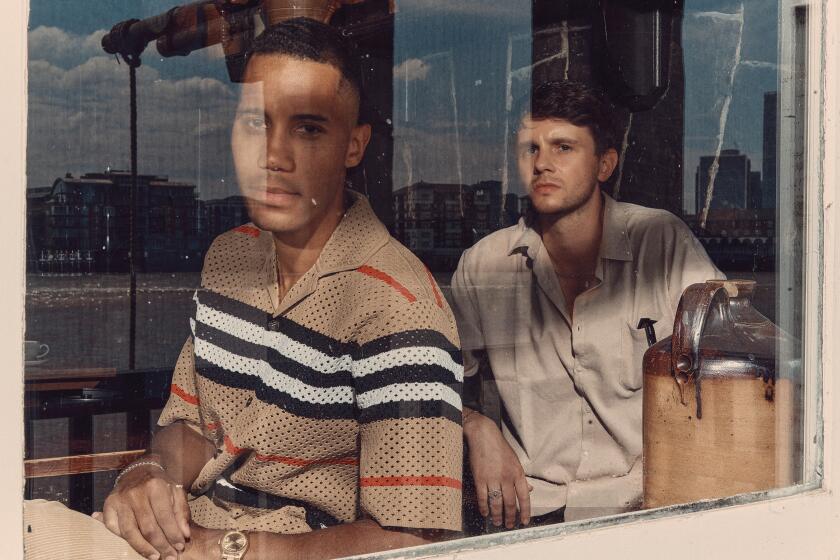

‘Industry’s’ depiction of London’s financial center may seem far-fetched. Creators — and former bankers — Konrad Kay and Mickey Down say otherwise.

Because of the ways that you refuse clear answers and keep an audience off-balance, are you ready for people to be upset by this?

Oh, yeah. I hope that this film starts conversations. I hope it starts debates. And it would be great if people are fighting about this movie in the parking lot. I’m not here to make safe movies. I’m here to stir the pot. And I’m interested why people are angry about it, why people get upset about it. I’m curious to see what that says about them. I think people will first of all be angry because she’s not a victim, and I’m not interested in keeping women in this box of victimization. That’s not who the character is. The character is here to get hers. I’m sure people are going to be upset about it, and I think that’s essential for the kind of film that I made.

I know you haven’t had a chance to see them, but there are a few other films in the program at Sundance — movies such as “Cat Person” and “The Disappearance of Shere Hite” — that also very much deal with the differing perspectives of men and women and the often unbridgeable divide between how they see certain situations. Why do you find the dynamics between men and women in heterosexual relationships such fertile ground for exploration?

No matter how much progress we’ve made, we still can’t figure each other out. I don’t think men and women can. There’s a lot getting in the way of that. And I think given the current climate we’re in, it’s made it a little bit worse because we’re all afraid to talk about things we might be feeling that are uncomfortable or not kosher. And instead of owning that and being honest about it, we’re just pushing it way down. Also, this film for me was about reckoning with a lot of unresolved feelings I had in my own personal experiences with these kinds of dynamics.

I was in a relationship with someone who was threatened by me and threatened by who I was and what I wanted out of life. And instead of being able to talk about it, the only way I knew how to cope was by making myself small, in a desperate bid to protect the relationship. It was never anything that either one of us could talk about because we would never want to admit that dynamic was real. We’re both supportive of each other. We’re both attracted to each other because of who we are. But at the same time, there were certain things kind of rotting at the core. And so for me it’s just about sounding the alarm to something that I think should not be normalized. Saying what for so long had been something that was very unspeakable to me.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.