‘Devotion’s’ director had an ace in the hole: his father, a Black Blue Angel pilot

JD Dillard doesn’t run on adrenaline; he runs on jet fuel. For the director of “Sleight” and “Sweetheart,” the new film “Devotion” — the thrilling, urgent story of Black Korean War aviator Jesse Brown — is the culmination of a lifelong obsession he shares with his father.

“All of my earliest memories are tied to aviation. The most literal one is burning my hand on the nose of a F-18 in my dad’s arms,” Dillard told The Times. “My dad would be part of the air show, and my mom and I would watch him, and I’d have little earplugs in because those shows are ungodly loud.”

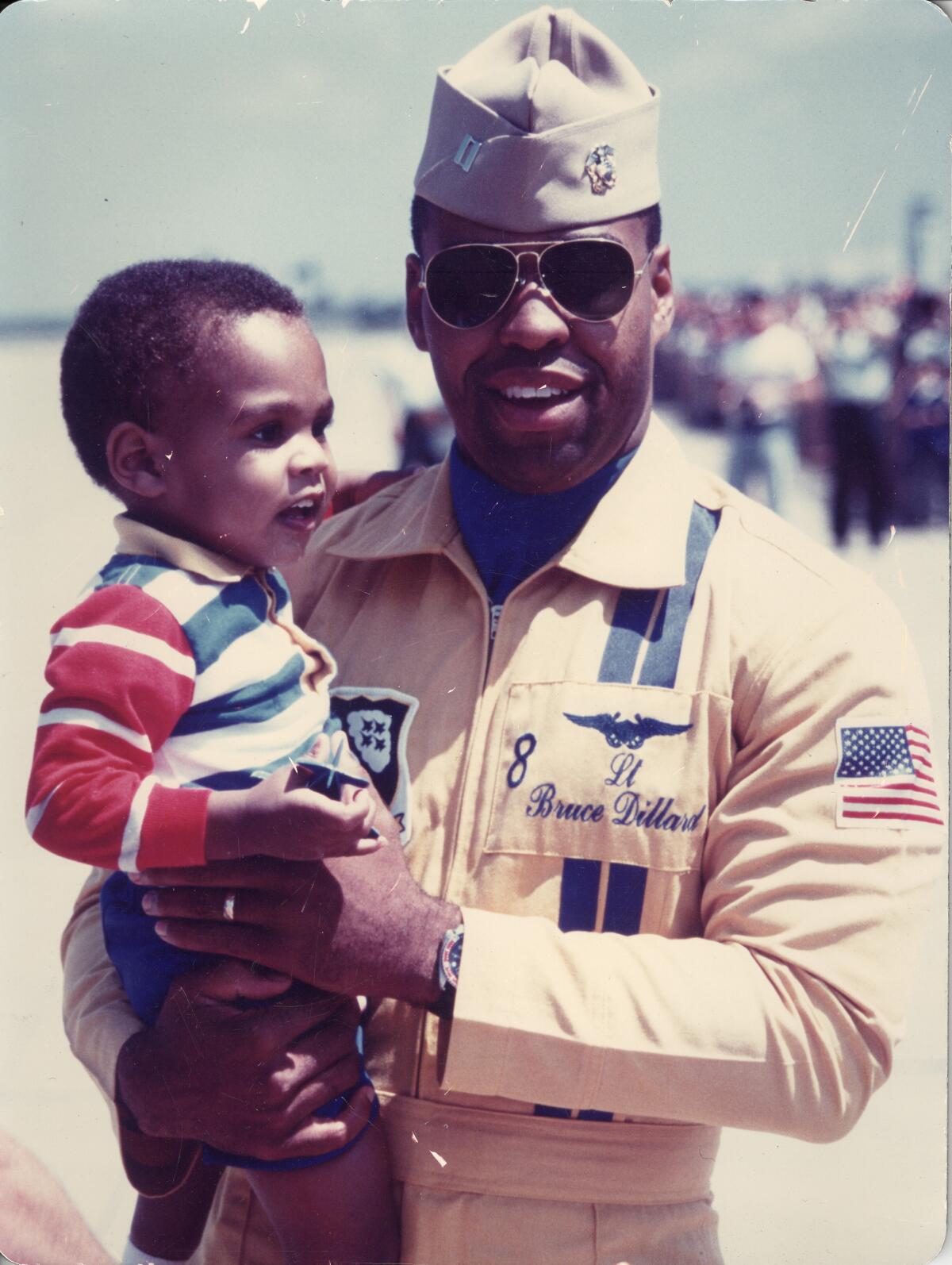

His father, Bruce Dillard, not only served as a naval aviator. He also toured with the Blue Angels, becoming only the second African American to join the ranks of the famed Navy aerobatics team. The younger Dillard would spend hours at their Pensacola, Fla., home watching VHS tapes of his dad’s rear-facing cockpit camera. “Ever since that age, I’ve been obsessed with masked characters,” the director said.

Directing an aviation film was never in doubt for JD Dillard. He just needed the right story.

The director didn’t know it, but Glen Powell had just the tale.

The charismatic actor is best known for his roles as a flier, playing astronaut John Glenn in “Hidden Figures” and a fictional pilot in “Top Gun: Maverick.” In 2016, while on a fishing trip with his family in Alaska, Powell read Adam Makos’ Korean War biography, “Devotion: An Epic Story of Heroism, Friendship, and Sacrifice.” To Powell, Makos’ recounting of the improbable friendship between naval aviators Brown (played in the film by Jonathan Majors) and Tom Hudner (Powell) in an America beset by segregation immediately felt cinematic.

“My grandfather was in the Korean War, and there haven’t been many movies about the Korean War in, like, 40 years,” Powell told The Times.

In 2017, the actor traveled to Concord, Mass., to meet with the real-life Hudner, a Medal of Honor recipient who retired with the rank of captain after a 27-year naval career. “What was really interesting is, his relationship with Jesse Brown was not one of them being best friends. They were kindred spirits,” said Powell.

Christina Applegate and Linda Cardellini spoke to The Times about the former’s multiple sclerosis, the ‘ambiguous’ ending of Netflix’s dark comedy and more.

The actor-producer next partnered with Black Label Media (the L.A.-based production company behind “La La Land”) to option Makos’ book. In 2018, while Jake Crane and Jonathan Stewart penned the screenplay, Powell met with the Brown family, then started an exhaustive search to find the right director to helm the complex narrative.

That search ultimately led to Dillard. “His dad was the second African American Blue Angel. He’s obsessed with aviation, and he’s got an incredible take on the movie,” said Powell.

Dillard felt an unusually emotional connection to the project. “I can’t remember the last time I cried reading a script,” he said. “To actually be that touched while reading a script is rare.”

Remembering how his dad would critique the inaccuracies in aviation movies, Dillard’s primary request of Black Label Media was to let him film realistic aerial scenes using historical planes actually flying.

Principal photography on “Devotion” kicked off soon after that, filming the rumbling aerial scenes meant to give the film a tactile feel that would separate it from the typical, VFX-heavy war flick. To fill the skies with vintage aircraft — Vought F4U Corsairs, Grumman F8F Bearcats, Hawker Sea Furies, Douglas A-1 Skyraiders and a Sequoia helicopter — Dillard turned to collectors for their semiretired warbirds.

Led by aerial coordinator Kevin LaRosa II (“Top Gun: Maverick”), Dillard and director of photography Erik Messerschmidt (“Mank”) experimented with different camera installations on the plane, balancing their desire for an immersive experience with the safety limits of antique aircraft better suited for lighthearted air shows than combat. Though it required more than a month of shooting at the height of the pre-vaccine pandemic, the hands-on approach proved worth the effort, considering that the pandemic then forced them to spend more than a year completing the additional effects in postproduction.

Majors said filming the aerials brought an elusive and unusually tangible quality to the filming. “I feel like this is something you can’t really fake. To actually feel it was incredible,” Majors said in an interview. “And when I say ‘feel’ it, I mean all of it. I mean the exhilaration of when you’re taking off, the exhaustion of trying to keep your lunch down when you’re drenched in sweat and your adrenal glands are pumping through the roof because you’re doing the impossible.”

Fittingly, the impossible sums up Brown’s life. Hailing from Hattiesburg, Miss., Jesse LeRoy Brown defied expectations by attending the Ohio State University at the height of segregation. He then enlisted in the U.S. Naval Reserve, where he encountered intransigent racism and racial violence from white cadets. The pain deepened Brown’s desire to achieve perfection.

Personal trauma influenced Bruce Dillard too. At age 14, the senior Dillard lost his father. That summer, his uncle took Bruce to an air show, where he first saw the Blue Angels. He knew he wanted to fly.

While filming “Devotion,” the younger Dillard often turned to his father for guidance that went beyond technical advice. “I’m not just asking my dad about the proper radio signal when you’re on a dive attack,” the director said. “But weirdly, the more helpful things were questions like: What was the tenor in the room when you told Mom you were going on cruise for the first time? How hard was that? And what about when you were on the ship and you felt insanely isolated yet still needed time alone? Where did you go?”

“Devotion” bucks the trend of other African American period pieces by skipping over traumatic scenes, so the audience sees just the result of Brown’s alienation, not the cause. That occurs as a revealing, fourth-wall-breaking shot capturing Brown, his face puffed by anger, turning the slurs flung at him by white folks back at himself for motivation. The decision frees the film from expectations to show Black bodily harm, and provides ample time to explore other parts of Brown.

Dillard took care to spotlight Brown’s life as a father and husband to Daisy Brown (Christina Jackson). The magic trick of the picture arises from how, ever so slowly, we move from Hudner and Brown’s partnership to Brown and Daisy’s relationship, a shift no doubt influenced by the closeness of the filmmaker’s mother and father. Jackson provides an obvious joy and, in the words of Majors, re-creates the “sanctuary” Brown felt.

“To act across Christina Jackson is to be very alive and to live,” Majors said. “Your body knows how to react. Your spirit knows how to react.… The game is, we’re gonna love each other fully. That is what she instigates.”

You could easily see how, with another director, “Devotion” might succumb to the white savior trope or become a how-to for solving racism in 138 minutes or less. In Dillard’s hands, however, the two aviators don’t move toward friendship but rather to a mutual respect as kindred souls.

The guarded Brown and the easygoing Hudner spend much of “Devotion” navigating the uneasy air that hangs between them. The intense physicality of Majors and the loose calm of Powell make for an intricate dance as Hudner learns that true allyship doesn’t spring from hollow gestures of friendship but from understanding the personhood of his Black counterpart. Ever so steadily, the pair forge a trust that carries an honest, emotional weight capable of devastating an audience because Hudner sees how he and Brown share an unbendable dedication to success and honor (a surprisingly humanizing steadfastness that Powell gracefully threads). “It’s not about the outcome,” Powell explained. “It’s about bleeding for a friend and really putting your skin in the game.”

In Blumhouse Productions’ “Sweetheart,” Kiersey Clemons finds herself trapped alone on an island with a sea monster that hunts at night. Clemons and director J.D. Dillard discuss filming a survival horror on a micro-budget.

That unique relationship immediately separates “Devotion” from, say, “Top Gun: Maverick,” as does the decision to dedicate a portion of the film’s box office to support the Brown Hudner Navy Scholarship.

Dillard’s personal relationship to the subject material by virtue of his dad was always evident to Powell. “[Bruce] Dillard was our sort of naval consultant on set, and [it was wonderful] just watching the way that JD brings his sisters into things and his mom and his dad,” said Powell. “I’m such a big believer in family and how that can change the ecosystem of making a movie from being a selfish environment to a very giving one.”

In “Devotion,” you can sense a partnership shared by father and son not solely defined by a shared love of aviation. Brown’s journey through white spaces, his search for camaraderie among his diverse colleagues, and his determination to achieve his dreams runs through the senior Dillard and the director himself. It’s how JD Dillard arrived here.

“He had that fire in his belly about my moviemaking dreams,” the younger Dillard said of his father. “He was very adamant about me sticking with it. If there’s something that you want to do, you have to relentlessly pursue it.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.