Review: Austin Butler is the King incarnate in Baz Luhrmann’s manic, hip-swiveling ‘Elvis’

Why hasn’t there been a great Elvis biopic yet? Well, Austin Butler wasn’t around to star as the King of Rock ’n’ Roll. At the center of Baz Luhrmann’s sprawling pop epic “Elvis,” a film as opulent and outsize as the King’s talent and taste, Butler delivers a fully transformed, fully committed and star-making turn as Elvis Presley. The rumors are true: Elvis lives, in Austin Butler.

Swirling around Butler’s bravura performance is a manic, maximalist, chopped-and-screwed music biopic in which Luhrmann locates Elvis as the earth-shaking inflection point between the ancient and the modern, the carnival and the TV screen, a figure of pure spectacle who threatened to obliterate the status quo — and did. Luhrmann takes Presley’s legacy, relegated to a Las Vegas gag, and reminds us just how dangerous, sexy and downright revolutionary he once was. He makes Elvis relevant again.

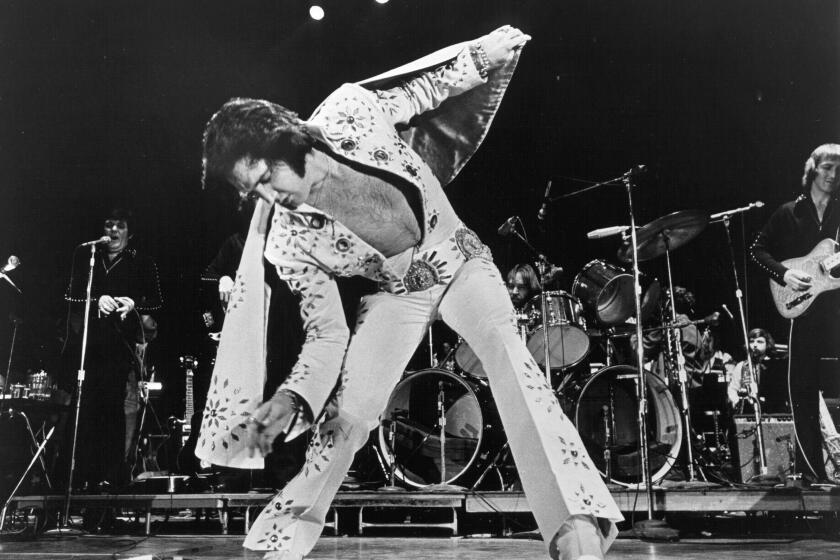

Butler leaves it all on the screen, embodying the raw, unbridled sexual charisma of Elvis onstage. He is jaw-dropping, nearly feral in his portrayal of Presley’s most memorable musical performances, from his early days to his 1968 comeback special and his Vegas shows, and Luhrmann shoots and edits these scenes to capture not just Butler’s performance up close but also the powerful impact Elvis had on his fans.

Written by Luhrmann, Jeremy Doner, Sam Bromell and Craig Pearce, the film crams Elvis’ entire career into two hours and 39 minutes of breathless filmmaking, focusing on the energy and emotional beats of Elvis’ journey, as well as his exploitation at the hands of his manager, Col. Tom Parker (Tom Hanks, heavily made up in prosthetics).

Baz Luhrmann’s splashy “Elvis” biopic attempts to make the King relevant to a new generation. But 50 years after Presley’s last Top 10 hit, is it too late?

Luhrmann editorializes on top of that, using a heavy hand in the edit to continually remind us of Elvis’ roots and motivations, and the cultural importance of his ground-breaking career. Contemporary music on the soundtrack links Presley’s performance of Black music to the popularity of modern hip-hop; snippets of Backstreet Boys and Britney Spears hits remind us that Elvis paved the way for teen idols and that his story is also a cautionary tale.

The first part of the film, focusing on his breakout as a pretty white boy from Memphis, Tenn., who sang the blues, is fast, loose and dynamic, a whirlwind of honky-tonks, tent revivals, Beale Street blues and country music shows. The pace is frantic; it can’t sit still in the same way that Elvis can’t keep still when he’s singing, overcome by the music. Cinematographer Mandy Walker’s camera never stops moving, pulling us into this whirlwind of newfound fame, the wheels of the machine turning faster than Elvis can keep up.

The speed and overstimulation is heady and intoxicating, a stark aesthetic and emotional contrast to later chapters in Elvis’ career. The Hollywood days are a montage of color and costume, an inauthentic facade, as he sells out to corporations and the bottom line. In the last section, Elvis is stultified and oppressed, sapped of color and life, isolated in his “golden cage” at the International Hotel in Vegas.

The story is told from Parker’s perspective, a curious choice, though it serves a greater narrative purpose. From his perspective, we understand the spectacle that is Elvis; the colonel nearly licks his chops at the sight of this newest carnival attraction: a handsome, erotic, racial-boundary-crossing young man with a rough croon and a jet-black forelock who can make teenage girls scream. With visions of merchandise dancing in his head, the colonel turns Elvis into a global icon, but as “Elvis” argues at every turn, the colonel tamed the singer’s unruliness and artfulness, forcing him into cheesy movie musicals and relentless touring.

Austin Butler poured everything he had into playing Elvis. The actor shares the grief, music and obsessive research that went into his portrayal.

Parker is the architect of Elvis’ downfall, extracting everything he can, clipping his wings, sanding down this culture-shifting force and offering him up as a titillating morsel of entertainment, the soul behind the talent tossed into the money-making machine and ground to dust.

The colonel’s narration and Hanks’ cartoonishly evil performance serve as a signed confession of guilt, as Luhrmann gives us Elvis as a Christ-like figure, a sainted martyr of rock ’n’ roll crucified on the cross of capitalism and greed.

While Butler humanizes Elvis, Luhrmann deifies him and argues that he possessed far more radical potential, both musically and politically, than he was allowed. His swiveling hips and jiggling knees weren’t just a portent of boy bands and pop icons to come — “Elvis the Pelvis” also threatened to usher in the sexual revolution and desegregate the South all at once, pushing rock ’n’ roll into the mainstream while starting the very first “culture war.”

“Elvis” isn’t just a reinvigoration of the Elvis myth. It’s also a resurrection of the King himself. Left the building? Not if Baz Luhrmann has anything to say about it.

‘Elvis’

Rating: PG-13, for substance abuse, strong language, suggestive material and smoking

Running time: 2 hours, 39 minutes

Playing: In general release June 24

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.