A TikTok contretemps, and a delicious eat-the-rich satire, at Cannes

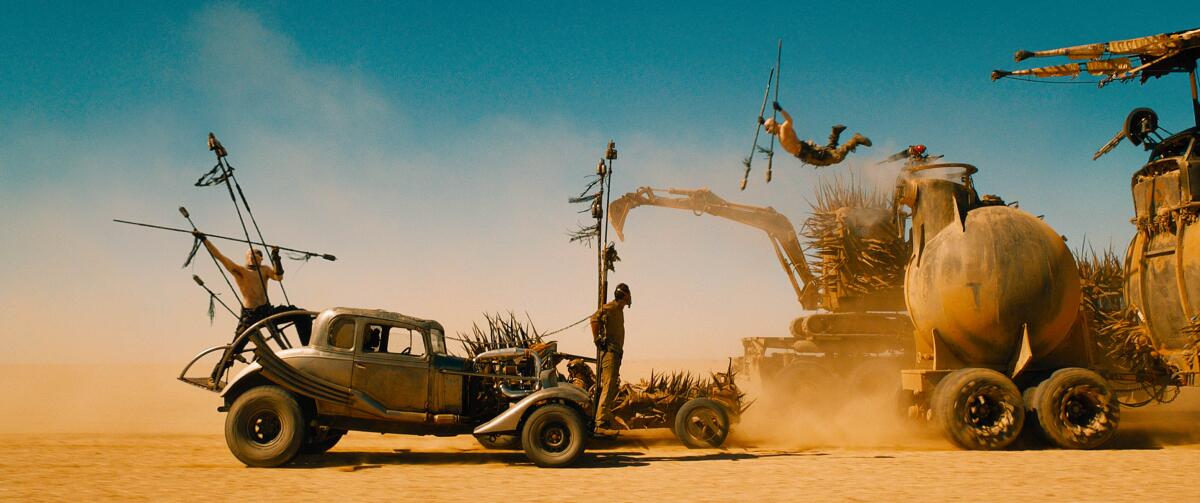

CANNES, France — The last time director George Miller brought a new movie to Cannes was in 2015, when his exhilarating “Mad Max: Fury Road” took the festival by (dust) storm. The movie played outside the main competition, as most Hollywood blockbusters at Cannes do. But as more than one onlooker observed, it felt like unjust treatment for a popular work of art that — in its beauty and kineticism, its political acuity and formal mastery — towered over most of the work vying for the Palme d’Or that year. When a filmmaker like Miller is at the peak of powers, the distinctions that festivals like Cannes often reinforce — between high and low, art and commerce — simply collapse.

Miller’s stature among world auteurs remains undimmed, even if his unusual new offering, “Three Thousand Years of Longing,” which premiered out-of-competition Friday night at Cannes (and will hit U.S. theaters in late August), isn’t one of his finer efforts. An intimately scaled chamber drama with a cosmic, fantastical overlay, the movie, adapted from A.S. Byatt’s short story “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye,” spins a fateful encounter between a literary analyst named Alithea (Tilda Swinton) and a millennia-old genie (a pointy-eared, furry-legged Idris Elba). The result is another showcase for Miller’s prodigious visual imagination, his deftness at integrating eye-popping visual effects into his storytelling. But in this case, the movie is itself a story about storytelling, which is where its specific problems begin.

The meeting between Alithea and the Djinn, as he’s known, plays out in the same Istanbul hotel room where Agatha Christie wrote “Murder on the Orient Express.” And as with Christie, there are mysteries to solve and puzzles to ponder. The Djinn, eager to be freed from the glass prison from which Alithea uncorks him, begs her to make three wishes, but the skeptical Alithea isn’t just careful what she wishes for. Being a professional narratologist, a scholar of mythic genres and archetypes, she knows that every wish-fulfillment fantasy — including the one she now finds herself in — is essentially a cautionary tale, a reminder that life’s shortcuts often result in a life cut short.

Or stretched out to an ungodly length, as is the case for the immortal Djinn, an outsized, outlandish figure whom Elba effortlessly invests with glimmers of humanity. Pleading his case to Alithea, the Djinn turns Scheherazade, telling stories of his past masters and the centuries of imprisonment he has endured as a result of their lust and greed. The individual tales, though ornamented with all manner of fabulous CGI curlicues, are overly busy and only mildly involving, and “Three Thousand Years of Longing” ultimately feels arch and encumbered in that self-conscious way that stories about storytelling often are. The best way to pay tribute to storytelling, really, is to tell a damn good story, not to keep clearing your throat in relentless anticipation of one.

And for better or worse, by design or not, this defensiveness about storytelling for its own sake feels especially symbolically weighty at this year’s 75th edition of the Cannes Film Festival. Because of its stature as the most important event of its kind, Cannes often stands in, or is assumed to stand in, for something larger than itself and generates headlines that resonate well beyond the film world. A selection of films is never just a selection of films; it offers a snapshot of the medium and speaks to prevailing winds in the global movie industry.

Along similar lines, a red carpet that has long been a symbol of glamour and tradition has, in recent years, become a #MeToo battleground — a place for women filmmakers to protest their lack of inclusion (and the sexism of Cannes fashion protocols). This year’s protests have gone much further: On Friday, before the gala premiere of “Three Thousand Years of Longing,” a member of the French activist group SCUM took to the red carpet to call out sexual violence against women in Ukraine.

And on Sunday, female protesters linked to the Cannes-premiered documentary “Feminist Riposte” unfurled a scroll listing the names of 129 recent French victims of “feminicide,” the intentional killing of women because they are women. That demonstration took place right before the competition premiere of “Holy Spider,” Ali Abbasi’s controversy-stirring thriller about the serial killer Saeed Hanaei, who targeted female sex workers in the Iranian city of Mashhad in the early 2000s.

Elsewhere in Cannes, the ongoing contretemps between the festival and Netflix — which, protesting its de facto ban from the event’s main competition, hasn’t brought a movie here since 2017 — may have cooled a little in recent years. But it remains a well-demarcated front line in the war between theatrical cinema and the so-called streaming revolution. As the festival turns 75 this year, a milestone that coincides with the industry’s long, slow emergence from a pandemic that’s wreaked havoc on the box office, it’s no surprise that Cannes likes to position itself as a proud defender of tradition, one of our last remaining bastions of cinematic art and integrity.

That image hit a snag this past week amid controversy over the festival’s newly struck collaboration with TikTok, a media partnership intended to maximize exposure for TikTok’s star personalities and introduce Cannes and its cinema to a new generation of social-media users. The well-regarded Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh (“The Missing Picture”) temporarily resigned as president of the festival’s inaugural TikTok short-film competition jury, claiming that the platform had tried to interfere with the jurors’ decisions. TikTok backed off and Panh re-joined the jury, but the takeaway was clear: The hot pursuit of sponsorship dollars and social-media “relevance” can exact a steep price. That can be especially true when it leads you to partner with a company whose products — short, easily consumable internet videos — would seem antithetical to the theatrical cinema that Cannes exists to promote.

But promote cinema Cannes does, not just through publicity-copy rhetoric but in its none-too-subtle programming decisions. The festival opened Tuesday night with Michel Hazanavicius’ “Final Cut,” a rickety remake of the Japanese dark comedy “One Cut of the Dead” and a sometimes touchingly sincere tribute to the joys and foibles of no-budget independent filmmaking. A more satisfying opening-night selection would have been the soon-to-open “Top Gun: Maverick,” which landed at the festival on Day 2, and which advanced its own deeply felt argument for the greatness of theatrical moviegoing — an argument stated most forcefully by its star, Tom Cruise, who was rewarded for his efforts with an honorary Palme d’Or.

Speaking of the Palme: The competition, while still in its early days, has already produced a number of strong selections. The biggest attention grabber so far is “Triangle of Sadness,” a viciously entertaining new social satire from a Swedish filmmaker, Ruben Östlund, who’s made them a career specialty. Östlund came to international prominence at Cannes years ago with the justly acclaimed “Force Majeure” and won the Palme in 2017 for “The Square,” a barbed, playful investigation of the modern art world. In the blunt, sprawling, nearly 2 1/2-hour “Triangle of Sadness,” he ascends to new levels of moral disgust while descending to new lows of topical unsubtlety. It’s a pretty good tradeoff.

Östlund’s target here is, surprise surprise, the one percent — or rather, the various members of the one percent, including arms dealers and Russian oligarchs, who find themselves on an extremely ill-fated yacht trip. Among their number are two hot young models (played by Harris Dickinson and Charlbi Dean, both terrific) who’ve been given free tickets in exchange for social-media exposure, which is of course a funny thing to see at a film festival that’s trading on social-media exposure to an unprecedented degree and unfolds next to a harbor full of yachts. But such ironies and incongruities are nothing new at Cannes, where on any given day you can don a tuxedo and walk up a star-studded red carpet to watch a movie excoriating the excesses of the Western world.

Still, “Triangle of Sadness” is the sharpest, grandest such excoriation we’ve had in a while, etched in Östlund’s beautifully composed master shots, which he then sets brilliantly askew once the boat sails into turbulent, pirate-infested waters. From there, the director pours on the acid — and the diarrhea, and the vomit — in some of the most remarkably modulated and attenuated gross-out comedy scenes in recent memory. A violently erupting toilet is one of a few links between this movie and the Palme d’Or-winning “Parasite,” one of many eat-the-rich satires that have proliferated in recent years.

What will this year’s Cannes jurors think of Östlund’s mash-up of Buñuelian chaos and “Gilligan’s Island,” complete with Woody Harrelson as increasingly soused skipper? Will they take note, as I hope they do, of Dolly De Leon’s revelatory performance as a yacht cleaning woman who nails her own “I am the captain now” moment? Stay tuned. There are still more movies to see, and yes, more stories to be told.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.