Appreciation: Ivan Reitman was the genial maestro of American movie comedy

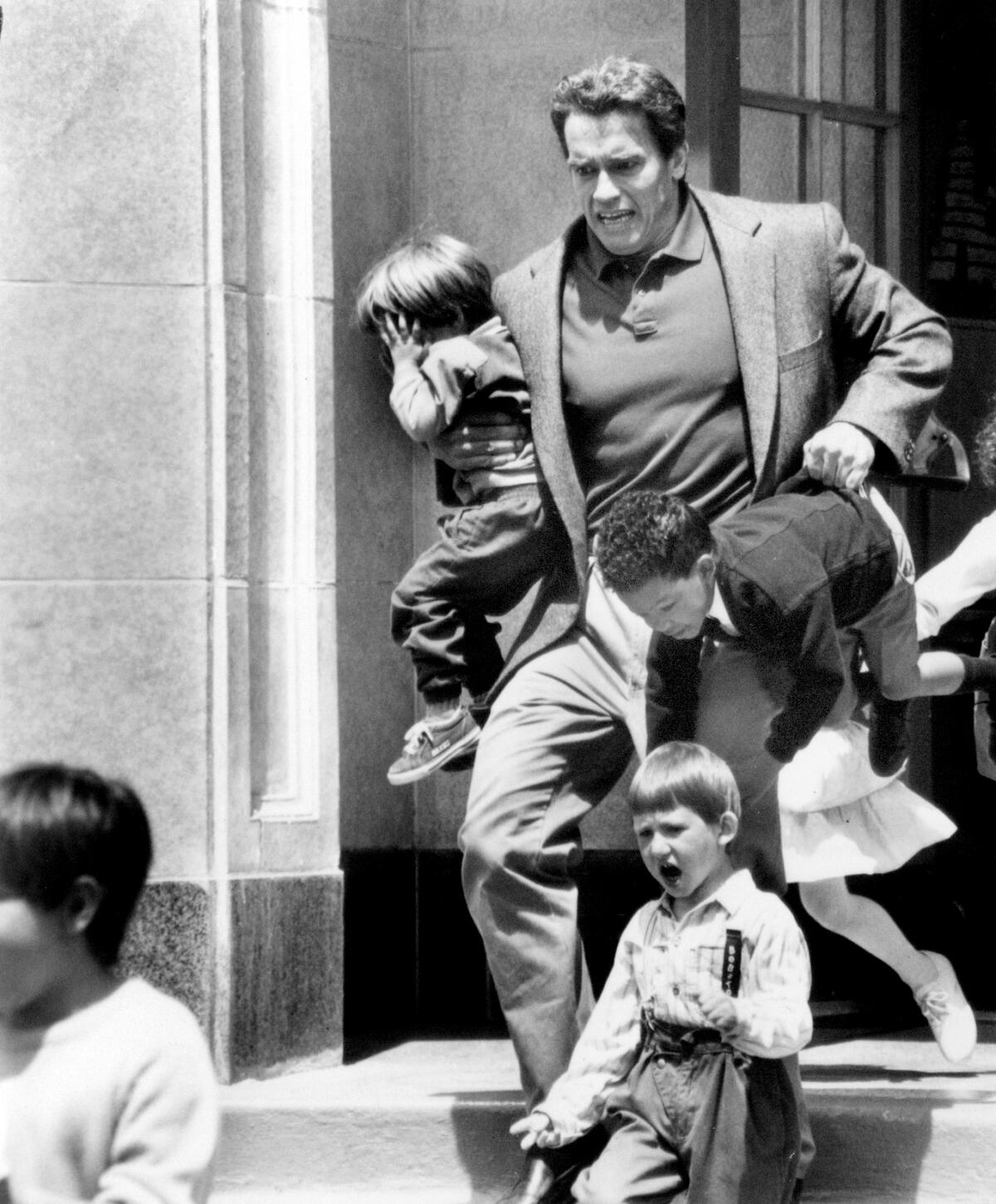

A few weeks ago, during one of those late nights when YouTube becomes a rabbit hole for the sleep-deprived, I found myself seeking out random clips from, of all things, “Kindergarten Cop.” That 1990 action-comedy directed by Ivan Reitman, who died this weekend at 75, is not what I’d call a personal favorite, though I couldn’t deny (or, for that matter, explain) its oddly persistent hold on my memory.

If recollection serves, I was only 8 when I first saw Schwarzenegger yell “SHUUUUUT UUUUUPPP!!!” at a class of unruly tots, an inauspicious start to possibly the least convincing undercover investigation in the history of the LAPD. Now, idly revisiting that and other scenes three decades later, I had questions: Was the movie as weird, incongruous and harrowing as I’d remembered? If they were making this now, how would they rework that startlingly intense shootout in a school lavatory? And of course: You’re not so tough without your car, are ya?

That last punchline still works beautifully, even if the rest of the movie works only in fits and starts. Like Reitman’s other hit efforts to mine the softer side of Austria’s most famously hard body — including “Twins” (1988), in which Schwarzenegger and Danny DeVito played separated-at-birth siblings, and “Junior” (1994), which reteamed both actors as the masterminds behind the world’s first human male pregnancy — “Kindergarten Cop” is something of a triumph of high concept over uneven execution. Or is it?

At their most memorable, Reitman’s comedies all but erase the line between goofy slapdashery and polished craft. To look back at his movies — many of them more amiable than side-splitting — is to rifle through an assortment of hits and misses, a catalog of comic imperfection. That’s no bad thing, really. Imperfection sometimes ages better, or at least more endearingly, than perfection.

Over the 16 or so features he directed over three decades (and the many, many more he produced), Reitman warmly embraced imperfection as both an innate human right and an overarching comic principle. He urged his actors to riff and improvise, an especially shrewd instinct when those actors included ad-lib masters like Bill Murray, Harold Ramis, John Candy, Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi. His emphasis on collaboration and rejection of hubris came naturally, perhaps, to someone who’d arrived at directing via producing. (His early producing credits included David Cronenberg’s early horror films “Shivers” and “Rabid,” followed by the career-catapulting 1978 hit of “National Lampoon’s Animal House.”) As a director, Reitman was written off early and often by his critics — even the more appreciative ones — as more journeyman than auteur. He wore that reputation with ease, much as he embraced the second-class citizenship that comedy is too often accorded in drama-first Hollywood.

No wonder that his own comedies so often celebrated disruptive, anarchic impulses, particularly within cherished American traditions and institutions: a teen summer camp in “Meatballs” (1979), the U.S. military in “Stripes” (1981) and the White House in perhaps his finest accomplishment, “Dave” (1993). You could impute the sly antiestablishment streak in these movies to a number of things, including Reitman’s outsider upbringing — he was born in Czechoslovakia to Hungarian Jewish parents, both Holocaust survivors, and moved to Canada when he was 4 — or his coming of age during the tumult and disillusionment of the ’60s.

Or you could just chalk it up to the naturally irreverent sensibilities of Reitman’s actors, and how closely attuned he was to their every instinct. The early one-two combo of “Meatballs” and “Stripes” made a particular star out of Murray, the most sneakily deadpan of nose thumbers, though he could of course rise to uproarious full volume as well: “It just doesn’t matter!” his camp counselor, Tripper, screams in the memorable motivational speech that gives “Meatballs” its climax.

A lower-key version of that rallying cry seems to permeate so many of Reitman’s comedies, with their sweetly goofy what-me-worry vibes. And those vibes achieved a blockbuster apotheosis with the smash success of “Ghostbusters” (1984), his biggest and most enduring hit, a movie whose sweet-spot combo of slime and silliness continues to fuel Hollywood’s nostalgia machine — most recently with last year’s “Ghostbusters: Afterlife,” in which he passed the director’s baton to his filmmaker son, Jason.

No appraisal of Reitman’s legacy would be complete, of course, without some acknowledgment of the “Ghostbusters” franchise’s more dubious die-hards, who reared their heads during the rollout of 2016’s female-led reboot. The vicious internet pile-on against that movie couldn’t help but feel like a curdled byproduct of the ’80s mainstream comedy ethos that Reitman and others helped establish, with its proud celebrations of male idiocy and female pulchritude.

Nonetheless, the ugliness of that particular “Ghostbusters” episode stands in glaring opposition to the gentle misfit spirit of Reitman’s 1984 movie, to say nothing of the humility and generosity roundly attributed to him by his colleagues. One of the truisms of Hollywood longevity is that a filmmaker’s greatest successes can become a mixed blessing, spawning toxic fan movements and inferior imitations, and sometimes boxing their creators into an unforgiving mold.

At the very least, Reitman eluded the curse of the latter. His post-1984 career may not have seen as outsized a hit as “Ghostbusters” (and that includes 1989’s “Ghostbusters II”), but neither can it be reduced to the output of a man repeating himself. Reitman continued producing, lending his name and time to movies as different as “Old School” and “Road Trip” (basically next-generation Reitman comedies); the Howard Stern comedy “Private Parts”; and Atom Egoyan’s Toronto-set hoot of an erotic thriller “Chloe,” which Reitman had originally planned to direct himself before stepping aside. (He decided the material was outside his wheelhouse; I can’t help but wish he’d taken it on.) He also earned his sole Oscar nomination, for best picture, as a producer on his son Jason’s 2009 George Clooney dramedy “Up in the Air.”

Reitman also directed several more movies, few of them masterpieces but all of them possessed of their distinctive pleasures, most of them performance-based. There was a rare rom-com lead turn from Natalie Portman in “No Strings Attached” (2011) and a perfectly cast Kevin Costner as an NFL general manager in “Draft Day” (2014), the last feature Reitman directed. Best of all, there was “Dave,” a Capra-esque charmer starring Kevin Kline and Sigourney Weaver, superbly matched as a presidential doppelgänger and his initially unsuspecting first lady. As a political farce, “Dave” may seem even tamer and less outrageous than it did on its initial release; its mix of gentle sentimentality and warm reassurance feels out of step with our more cynical times. Which is precisely why, as with so much of Reitman’s work, it’s hard to resist revisiting.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.