Review: Amid delays and scandals, a middling ‘Death on the Nile’ slumps into theaters

The Times is committed to covering indoor arts and entertainment events during

the COVID-19 pandemic. Because attending carries risks during this time, we remind readers to follow health and safety guidelines as outlined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and local health officials.

There’s at least one moment in “Death on the Nile,” Kenneth Branagh’s latest Agatha Christie adaptation, when what’s on-screen brushes up uncomfortably against what’s off-screen. Linnet Doyle, an enviably rich socialite taking a honeymoon cruise down the Nile River, has just been found shot to death in her stateroom; her husband, Simon, is an inconsolable wreck, sobbing noisily over her body. Watching this oddly strained, curiously revealing scene, I had to wonder why Simon’s grief rings so hollow. Could it be because the character is presented, in both the movie and Christie’s 1937 novel, as a dumb, opportunistic cad? Or could it have something to do with the fact that he’s played here by Armie Hammer, the former Hollywood golden boy who stands accused by multiple women of sexual assault and abuse?

Some would doubtless prefer I glossed over that scandal, as if it were incidental or irrelevant to the movie’s quality. Separate the art from the artist, or the product from the pretty face, or whatever. This is often easier said than done, depending on your ability to dissociate fiction from reality, even if that reality is disputed. (Hammer has denied the allegations.) I’m not too bad at it myself; compartmentalizing, much like suspending disbelief, is part of a critic’s job and a moviegoer’s prerogative. Still, it seems odd to sidestep the issue of Hammer’s alleged misconduct when the film’s own distributor clearly regards it as more than a minor inconvenience.

When the allegations against Hammer emerged last year, Disney reportedly considered reshooting his scenes with another actor, in much the same way that Christopher Plummer replaced the disgraced Kevin Spacey in “All the Money in the World.” (That call was made by director Ridley Scott, a producer on “Death on the Nile.”) In the end, the role of Simon Doyle was too prominent, and Hammer’s interactions with the rest of the ensemble too extensive, to make such damage control feasible. And so, after multiple release-date delays — mostly chalked up to the pandemic, though you needn’t be Hercule Poirot to suspect other motives — the film finally steams into theaters this week, reeking of damaged goods and seeking an audience that won’t mind. It may well find that audience, especially among those who ate up its predecessor, “Murder on the Orient Express.”

Like that 2017 hit, “Death on the Nile” is a decidedly mixed bag. It’s nowhere near as good as John Guillermin’s still-delightful 1978 film adaptation, with its authentic Egyptian locations and memorable turns by Peter Ustinov, Mia Farrow, Bette Davis, Maggie Smith and Angela Lansbury. But neither is it as bad as some may have expected or even hoped. Christie’s story, one of her finest, is hard to screw up, even when Branagh and his returning screenwriter, Michael Green, seem bent on proving otherwise. Their movie is an often fussy, hectic confusion of old-timey pleasures and 21st century sensibilities, a mash-up that makes for some especially incongruous visual choices. (Shot by Haris Zambarloukos in England and Morocco, the movie leans heavily on digitally conjured Egyptian locations, a choice that meshes none too seamlessly with its use of 65-millimeter film stock.)

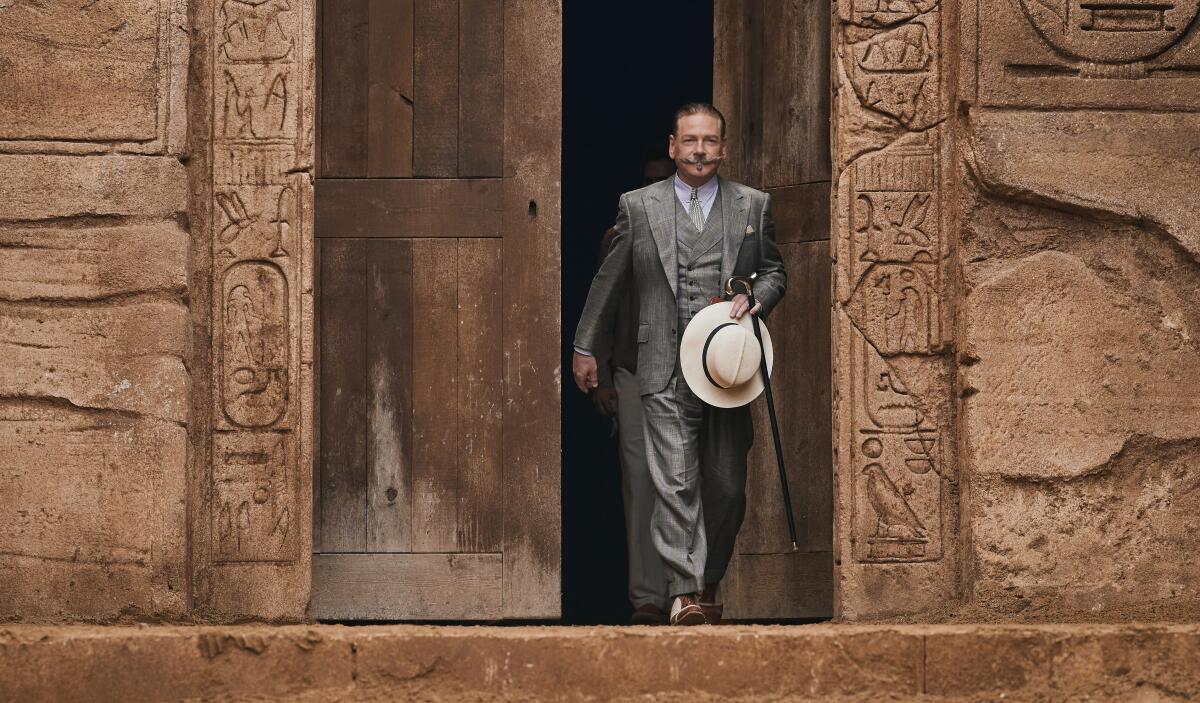

Once again, Branagh’s all-over-the-place direction — poor lighting, clumsy blocking, ill-motivated camera placement — proves rather less involving than his witty, touching performance as Poirot, the mustachioed Belgian detective known for his extraordinary deductive powers, obsessive-compulsive tidiness and sweet tooth. Joining him this time in the swirling ensemble cast are an underwhelming Gal Gadot, an outstanding Emma Mackey, an acerbic Annette Bening, a boisterous Tom Bateman (reprising his “Orient Express” role as Poirot’s friend Bouc), a sultry Sophie Okonedo, a fierce Letitia Wright and a nearly unrecognizable Russell Brand. And, yes, a prominent Armie Hammer, whose louche swagger is surprisingly effective here, even if it reverberates in ways that few at the time of filming could have anticipated.

Some viewers may find those reverberations appalling, assuming they watch the movie in the first place. I’m loath to get too specific, especially for those unfamiliar with Christie’s story, but let’s just say the plot hinges in no small part on Simon’s sexual magnetism, the degree to which he pursues and manipulates — and is pursued and manipulated by — two equally ruthless women. And the movie translates that dynamic to the screen with an unapologetically, sometimes awkwardly bawdy energy: We first meet Simon in a sweaty London nightclub, leading his fiancée, Jacqueline de Bellefort (Mackey), through a routine that looks awfully twerky for the ’30s. “We have sex a lot,” Jacqueline confides to her childhood friend Linnet (Gadot), who will soon swoop in and steal Simon for herself with a multimillionaire’s casual entitlement.

Within weeks, Linnet and Simon are having a destination wedding in Egypt, where Poirot is a last-minute guest and a furious, vengeful Jacqueline stalks the happy couple at every turn. As you might expect, the jilted lover isn’t the only passenger aboard their Nile riverboat who has reason to wish Linnet dead. The others include a disgruntled assistant (Rose Leslie) and an unscrupulous moneyman (Ali Fazal) whom no one, regrettably, accuses of running a “pyramid scheme.” Those with less discernible motives include Salome Otterbourne (Okonedo), written by Christie as a bestselling trash novelist but here reconceived as a popular blues singer; her niece and business manager, Rosalie (Wright); and Linnet’s outspoken communist godmother (Jennifer Saunders), who arrives with a nurse companion (Dawn French) in tow.

Branagh and Green have largely retained the well-oiled mechanics of Christie’s dazzling murder plot, with its smoking guns, stolen jewels and strategic use of nail polish. But they have made any number of tweaks elsewhere, mostly with an eye toward lending the 1930s setting a sharper political edge. The cast has been streamlined but diversified. Racism and homophobia are among the story’s secondary villains. Some of these refurbishments prove more effective than others: In the end, we’re still watching a party of privileged tourists while the Egyptian locals remain largely in the background. (That’s arguably an improvement over how they’re treated in the novel, hardly the only Christie book to be marred by exoticizing impulses and Orientalist attitudes.)

Where the script remains most productively faithful to the book is in its atmosphere of lush, doomy romanticism; Jacqueline is far from the only character here grappling with the exquisite cruelties of l’amour fou. Although perhaps overripe with locally appropriate references to Antony and Cleopatra, the dialogue has its earnest charms: As one character notes on the eve of disaster, love is “not a game played fair. There are no rules.” Indeed, if you were to take a drink every time someone in this movie described love as the most powerful, all-consuming and dangerous force in the world, you’d be passed out faster than Poirot on the fateful night someone slips him a sedative.

Ah, Poirot. Branagh clearly loves this character, leaning into the famously persnickety mannerisms even as he insistently locates an emotional core beneath the immaculate white suit and whiskers. Maybe too emotional; I remain skeptical of these movies’ insistence on fleshing out details of Poirot’s romantic past, elaborated here in a black-and-white prologue set during the detective’s World War I military service. These are sweet, humanizing but also franchise-padding touches, and I object to them on more or less the same grounds that I object to the recent sentimentalizing of James Bond, brilliantly played as he was by Daniel Craig. We return to these sleuths again and again because of how good they are at what they do, not how bad they are at love.

‘Death on the Nile’

Rated: PG-13, for violence, some bloody images and sexual material

Running time: 2 hours, 7 minutes

Playing: Starts Feb. 11 in general release

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.