From ‘Nanny’ to ‘The Exiles,’ a virtual Sundance puts a human face on past and present horrors

Is it horror or just real life? The question kept coming up at this year’s all-virtual Sundance Film Festival — particularly in the American dramatic competition, where the buzzier entries included “Master,” Mariama Diallo’s bold if muddled chiller about Black women in white-dominated academia, and “Palm Trees and Power Lines,” Jamie Dack’s jolt-free but thoroughly unsettling portrait of a teenager falling into a sexual predator’s clutches: not a horror film, per se, but no less horrifying for it. The jury’s favorite in this field was also its most effective and emblematic demonstration of genre-drama hybridization in action: Its grand jury prize went to “Nanny,” Nikyatu Jusu’s tense and lyrical domestic thriller about a Senegalese immigrant, Aisha (the remarkable Anna Diop), who spends her days minding someone else’s daughter while dreaming of the son she left behind.

Before long, Aisha is dreaming about much more: Moldy specters rooted in West African folklore invade her sleep, as do troublingly beautiful visions of the vast ocean that separates her from her son. These visions, frightening as they are, don’t function the way horror-movie jolts typically do; Jusu, a Sierra Leonean American filmmaker, is more interested in teasing out their mythopoetic resonance than in giving you the outright heebie-jeebies. As Aisha navigates a world where cluelessly condescending white smiles hide all manner of danger and hostility, she becomes haunted, literally and emotionally, by a home she can’t — and shouldn’t — forget.

Horror cinema has long been in the business of mining terror from the everyday, of linking surface scares to primal subtexts — something often lost on champions of so-called elevated horror, or at least those who regard it as a relatively new development. Still, there’s no denying that Sundance has played a particular role in fostering this latest strain of cinematic scare-making and has granted a platform to some of its most highly regarded practitioners. Both Jordan Peele’s “Get Out” (2017) and Ari Aster’s “Hereditary” (2018) were first unveiled at late-night screenings in Park City, Utah, the high-altitude town where this festival is held annually. (Maybe we should call it elevation horror, a phenomenon that dates at least as far back as 1999’s “The Blair Witch Project,” the most famous of Sundance’s breakout freakouts.)

“Nanny,” “The Exiles” won grand jury prizes in U.S. dramatic and documentary competitions. “Cha Cha Real Smooth” and “Navalny” took audience prizes.

This year, for the second year in a row, the COVID-19 pandemic forced Sundance to go entirely online, keeping festival-goers away from Park City and sapping pictures like “Nanny” of some, if not all, of their visceral charge and packed-house immediacy. I’d have loved to have heard the shudders and giggles ripple through the crowd for Andrew Semans’ enjoyably ludicrous mad-mom thriller “Resurrection,” which played in the festival’s high-profile Premieres section. Rebecca Hall, a Sundance mainstay as both actor (“Christine,” “The Night House”) and director (“Passing”), gives a typically superb frayed-nerves performance as a woman whose happy facade begins to crumble with the reemergence of a figure from her past (a magnetically loathsome Tim Roth). The gripping if sometimes alarmingly straight-faced results suggest “Martha Marcy May Marlene” by way of David Cronenberg — old traumas, new flesh — if not as impeccably controlled as that formulation suggests.

Women in peril, in other words, were out in full force at virtual Sundance 2022. Witness Lea (Lily McInerny), the 17-year-old protagonist of “Palm Trees and Power Lines,” who falls into the grip of a man twice her age (Jonathan Tucker) in what initially seems like an unusually unflinching Lolita narrative but soon reveals itself to be something even more ineluctably sinister. Dack, who won the U.S. dramatic competition’s directing prize, establishes a sense of humdrum reality that turns hypnotic, then tragic, by slow-burning increments. Weirdly, days after seeing “Palm Trees,” I couldn’t help but flash back on it while watching another teenager forge a forbidden bond with a male stalker in Carlota Pereda’s “Piggy,” a blood-curdling standout of the festival’s Midnight sidebar. Starring a terrific Laura Galán as a teenager who’s mercilessly bullied for being overweight, this grisly picture, set in a village inside Spain’s autonomous community of Extremadura, bears the clear imprint of “Carrie” — the red-drenched key art is no coincidence — but deftly sidesteps revenge-thriller obviousness.

The possibilities of violence, as both inflicted and endured by women, are also slyly subverted in Riley Stearns’ dramatic competition entry, “Dual,” starring a deadpan Karen Gillian as both a terminally ill woman and the clone she ill-advisedly agrees to have engineered as her own replacement. Like Stearns’ earlier “The Art of Self-Defense,” this science-fiction-inflected dark comedy feels askew in ways both alienating and amusing; it unfolds in a world where nearly everyone speaks in an unfiltered, hyper-eloquent patter and a fighting instructor (this one played by an amusing Aaron Paul) again proves crucial to the proceedings.

The cloning-replacement element gives “Dual” a striking conceptual similarity to the otherwise very different “After Yang,” a lovely, melancholy drama about human grief and robot memory, written and directed by the Korean-born filmmaker Kogonada (“Columbus”) and starring a terrific Colin Farrell. “After Yang” first premiered last summer at the Cannes Film Festival, where it drew mixed responses. For whatever reason, it encountered a considerably more favorable reception at Sundance, which is just one example of why festivals remain individually vital even amid the contracting economics of a pandemic-affected, streaming-driven industry. Different festivals serve different purposes and different audiences, and even a virtual Sundance remains no exception: The buzz may no longer circulate through packed shuttles and crowded lobbies, but it circulates nonetheless.

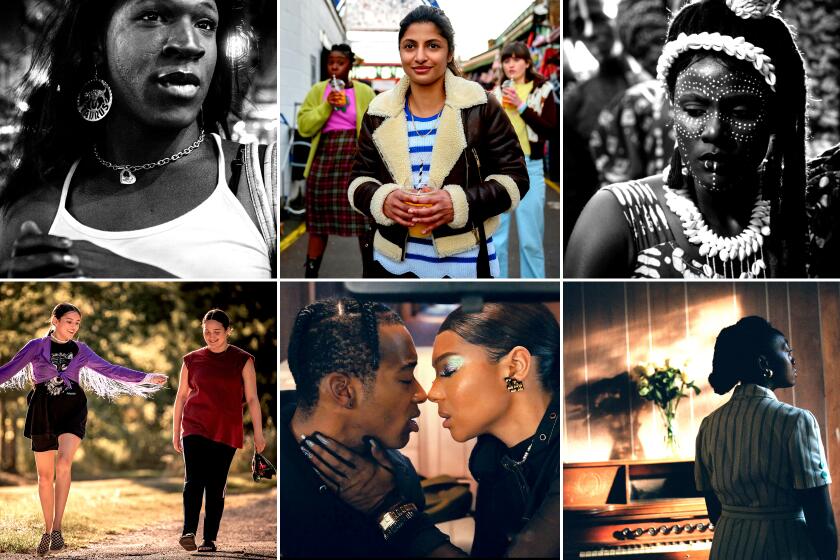

The Times team shines a spotlight on select titles from the 2022 Sundance Film Festival, including personal favorites and titles emblematic of this year’s virtual gathering.

Certainly the mix of social-media enthusiasm and exasperation was vocal enough to send me to “Cha Cha Real Smooth,” an ingratiating showcase for its writer, director and star, Cooper Raiff. He plays Andrew, a directionless twentysomething who gets hired as a party starter on the local bar/bat mitzvah circuit, only to lock eyes with an older woman named Domino (Dakota Johnson), who seems poised to topple into his arms. All of which may make “Cha Cha Real Smooth” sound like the latest exercise in multitasking indie narcissism, and maybe it is; still, Raiff has a gift for modulating his own considerable charm, and he was wise to cast Johnson, who, not for the first time, coolly pockets the picture. In Andrew’s eyes, Domino is another woman in peril, in desperate need of his emotional rescue; the movie, which unsurprisingly won the dramatic competition’s audience award, gently and affectionately corrects his vision.

Winning if overindulgent crowd-pleasers are par for the course at Sundance; so are consciousness-raising documentaries in which attention-grabbing personalities jostle alongside hard-hitting subjects. Both could be found in Violet Columbus and Ben Klein’s absorbing, fluidly structured “The Exiles,” which received the grand jury prize in the U.S. documentary competition. A look back at the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre and a fierce call for the U.S. and other world nations to hold China’s ever more authoritarian government to account, the movie draws its energy and focus from the righteous, relentless advocacy of Chinese American filmmaker Christine Choy, whose footage of 1989 protesters is here lovingly excavated and forcefully reexamined.

A memory piece many times over, “The Exiles” also pays tribute to Choy’s Oscar-nominated 1987 documentary, “Who Killed Vincent Chin?,” whose investigation of anti-Asian violence felt like more of an outlier back then — a time, Choy reminds us, when diversity among filmmakers (to say nothing of motion picture academy voters) was virtually nonexistent. Happily, that’s no longer the case, and Sundance deserves no small share of the credit; its investment in female filmmakers and filmmakers of color long predates the recent outcries generated by #MeToo and #OscarsSoWhite — a commitment to inclusivity proudly upheld by its estimable programming team, led by festival director Tabitha Jackson and director of programming Kim Yutani. One of the pleasures of this year’s festival is a vivid sense that representation is becoming ever more specific and multifaceted: You could see it in a documentary like “Aftershock,” Paula Eiselt and Tonya Lewis Lee’s damning look at how systemic medical racism has led to devastating rates of maternal death and morbidity among Black women. (The film won a special jury prize for impact from the U.S. documentary jury.)

The Sundance Film Festival entry “Nanny” follows an immigrant domestic worker in New York City tormented by supernatural forces.

You could also see it in the top two prizewinners in the festival’s World Cinema programs, both of which offered stirring portraits of animals and their human caretakers struggling in the wake of environmental decay. The grand jury prize for international documentaries went to “All That Breathes,” Shaunak Sen’s beautifully observed film about two Indian brothers who set up an in-home hospital for black kites, birds that have become increasingly endangered by pollution in Delhi. Over in the international narrative competition, the grand jury prize was awarded to Alejandro Loayza Grisi’s llama drama “Utama,” a movie of stark Bolivian landscapes and startling emotions in which a terrible drought threatens the way of life of an elderly couple and their herd. (The llamas, tagged with pink tassel-like ear ribbons, are all inveterate scene stealers.)

I’ll end with a word on Chase Joynt’s “Framing Agnes,” which premiered in the festival’s Next section devoted to innovative low-budget work, and which scored both the jury and audience awards in that program. Meta to the max — but intuitively, revealingly so — the movie excavates an invaluable archive of interviews conducted with transgender individuals at UCLA in the 1960s, chief among them the pseudonymous Agnes. Joynt and a cast of trans actors have performed excerpts from those interviews, adopting the deliberately stilted, stuffy format of a 1960s talk show; these stylized re-creations are interspersed with personal ruminations from the actors on what it feels like to imagine and inhabit another trans person’s experience.

Dizzyingly prismatic yet unfailingly lucid in its examination of the many layers of gender, sexual and racial identity, “Framing Agnes” releases wave after wave of insights over its fleet 75-minute running time. Among other things, it’s a too-rare reminder that representation, even vital, necessary representation, extracts a not-insignificant personal cost from those being represented. You leave this movie thinking about trans women like Agnes, but also about the many trans women unlike Agnes, and also about the pitfalls of storytelling that runs the risk of tokenizing and reducing even as it exalts and illuminates. It’s a question that I hope Joynt and other filmmakers never stop posing of themselves and their audiences, from this Sundance to the many still ahead.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.