Sidney Poitier leaves a rich legacy: the ‘freedom to choose’

In his long and rich life, Sidney Poitier, who died Jan.6 at age 94, leaves behind many legacies. But it is his career in Hollywood that may have been the most transformative, changing both an industry and a culture .

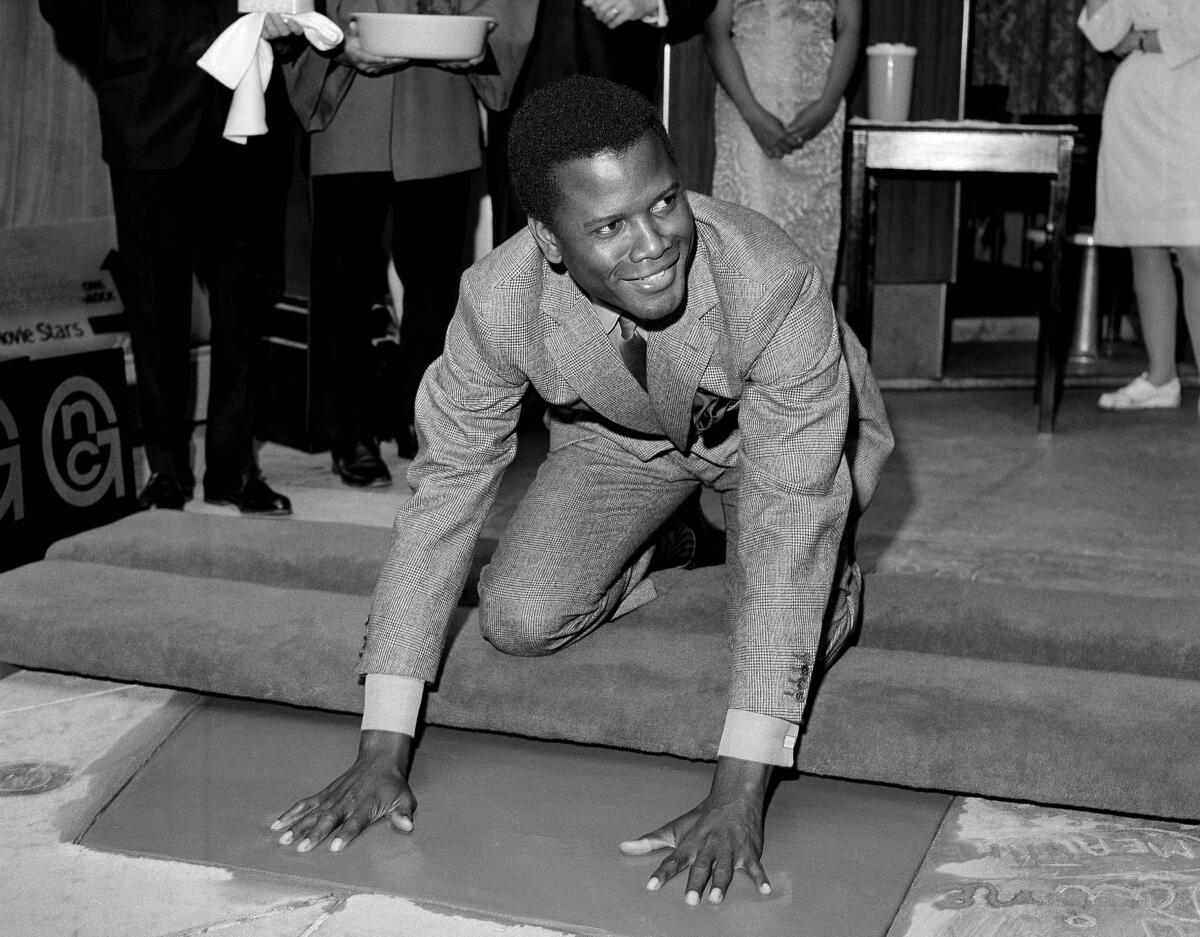

Having already found some success in the theater, Poitier made his screen debut with “No Way Out” in 1950. He would become the first Black man to be nominated for the Academy Award for lead actor with 1958’s “The Defiant Ones.” He used his stardom to help bring Lorraine Hansberry’s play “A Raisin in the Sun” to Broadway in 1959, where he originated the role he would play in the 1961 film adaptation. He then became the first Black actor to win the Oscar with 1963’s “Lilies of the Field.” With 1980’s “Stir Crazy,” Poitier was the first Black director to make a film that grossed more than $100 million at the box office.

Yet simply listing his accomplishments cannot capture their full meaning.

“For such a long time, he was understood in terms I think were too narrow,” said Jacqueline Stewart, chief artistic and programming officer at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Before the museum opened in September, its 10,000-square-foot entry hall was named the Sidney Poitier Grand Lobby in recognition of his humanitarian work and artistic achievements.

“For many people, he really exemplified the trajectory of integration in America. Which is certainly true,” said Stewart.“But at the same time, there was something just so distinctly Black and proud about Sidney Poitier.

“So for me, it’s a moment to really look back at the nuances of his performances, to appreciate just the complexity of the decisions that he had to make as a film artist about what projects to take up and which ones to turn down and to really think about what it meant for him to feel such a tremendous responsibility for representing a whole race of people. And he understood that not just in terms of an American context, he understood what it meant on a global scale,” she added.

Because of that, it can be easy to overlook that those accomplishments came for a reason, that he was a fine actor and an outstanding movie star.

“There is no other actor like him. Very few people have that combination of charisma and talent that makes someone a true movie star, and very few of them are allowed to be Black,” said Maya Cade, creator and curator of the Black Film Archive. “To remember him is to remember how beautiful he was onscreen and how he established power and used it.”

When Poitier received the Oscar for “Lilies in the Field,” it did not represent the pinnacle of his career, only one stop along the way.

“It’s certainly a moment in which he is celebrated, and we might say that Hollywood is also celebrating itself, ‘Look, we’re turning a corner here,’” said Stewart. “We play that moment in the museum and the energy of the applause for him at that ceremony — there are whistles and cheering — it’s something that it really seems that the whole industry wanted to see happen at that moment.”

In his acceptance speech,Poitier acknowledged all who had come before him. He recognized that the award was part of a continuum, though he perhaps had no idea how long it would take for someone else to follow through the door he had just opened.

“And I would imagine that this was a source of frustration for him, because he says in his speech, it’s been a long journey. And I don’t think he’s talking just about his own career. I think he’s talking about the experiences of Black artists in Hollywood much more broadly. And it continued to be a really long journey after him,” said Stewart.

“I think that the real lesson of that moment, we’ve seen it in subsequent waves of attention and recognition of Black actors and across the history of the Academy Awards. But none of that would’ve happened at all if it had not been for that first recognition of him as a bona-fide movie star. It just set a benchmark that could be pointed to, to say, ‘The talent is out there, Hollywood,’ that this is possible. And it’s critical that we remember that.”

It would not be until 2002, when Denzel Washington won for “Training Day,” on a night in which Poitier also received an honorary Oscar for his artistic and humanitarian efforts, that another Black man would take home the award. On that same night, Halle Berry became the first Black woman to win lead actress for “Monster’s Ball.”

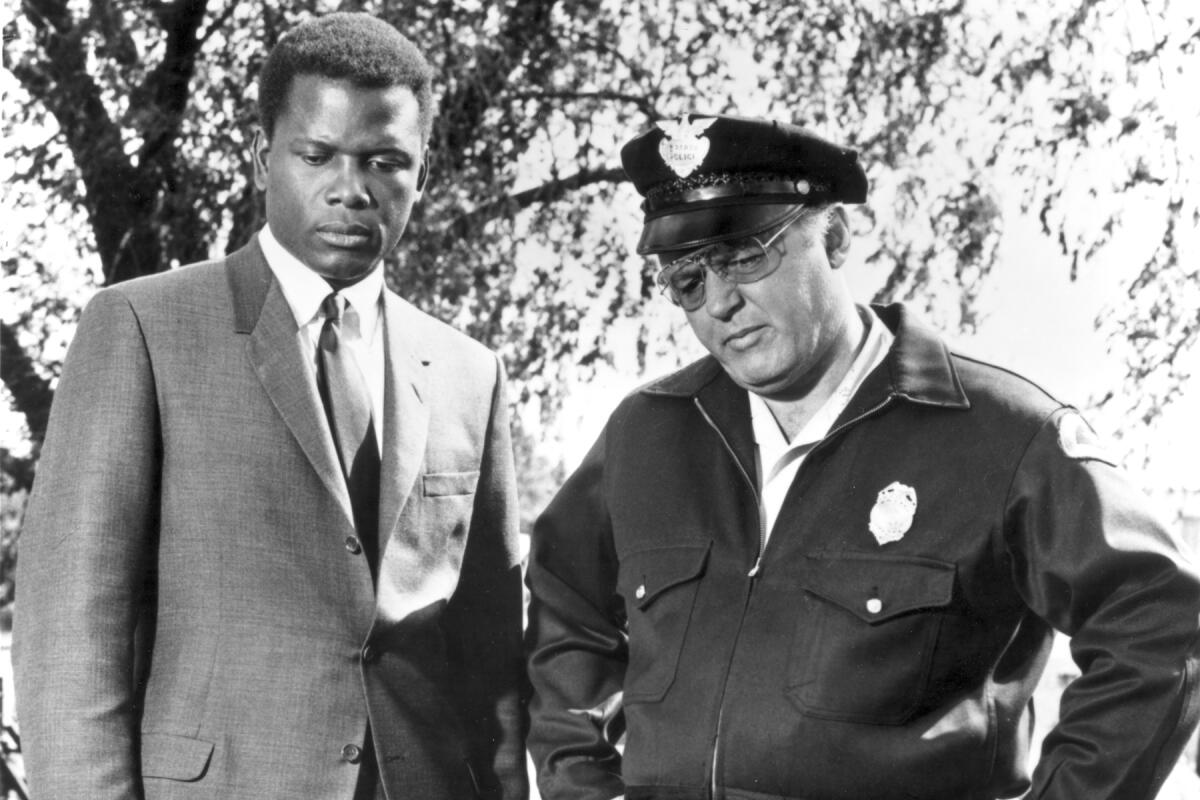

In 1967 alone, Poitier saw the release of “To Sir, With Love,” “In the Heat of the Night” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” and became a box office sensation. “In the Heat of the Night,” directed by Norman Jewison, would win the Oscar for best picture and the lead actor award for co-star Rod Steiger. Poitier was not nominated.

In the days since Poitier’s death, much conversation has circled on a moment in “In the Heat of the Night.” An older racist white man, a powerful local plantation owner played by Larry Gates, slaps Poitier’s character, Virgil Tibbs, a Philadelphia detective who has come to a small Southern town to investigate a murder. Without hesitation, Poitier slaps him back.

“It’s a moment that resonates with so many people now, because those frustrations continue to exist in such a palpable way,” said Stewart. “As a film historian, it’s a fascinating moment, because there’s a really interesting relay of glances that happens in that scene, the quickness of the slap back, and then we see this kind of stoic look on his face. The fearlessness is amazing. And then we get a cut to Rod Steiger, who has watched this slap. It’s a moment that recognizes what that kind of action means both for Black people and for white people.”

Stewart recalled James Baldwin writing in his book “The Devil Finds Work” how Black audiences jeered a moment in “The Defiant Ones” when Poitier’s character sacrificed his freedom to help his white counterpart, played by Tony Curtis. Those same audiences cheered Poitier’s “In the Heat of the Night” slap a decade later.

“Over the course of his career, we do see ways that he is charting this progression from expectations of a kind of Black subservience or obligatory, maybe superficial, representations of brotherhood toward a more direct representation of the tensions behind those relationships,” said Stewart.

As he began to step behind the camera as a director, first with 1972’s “Buck and the Preacher,” a western in which he starred with Harry Belafonte and Ruby Dee that was a direct rebuke to many of the genre’s racial tropes, Poitier continued to break new ground for himself as an artist.

“What his run of the ’60s really means to me is that he understood the role he was forced to play during the height of his fame, and what choosing otherwise could mean for the growing civil rights movement,” said Cade. “His kind of directorial turn, when I think of ‘Buck and the Preacher,’ he just understood that his caricature of perfection that catapulted him to fame also put him at odds with a lot of Black people because of the role he had to play. So it’s a studio film that openly questions the inhumanity of whiteness and fights against that.”

Poitier’s biggest hits as a director were comedies such as “Uptown Saturday Night” and “Let’s Do It Again,” which had a looseness often missing from the films that had made him a star, leading up to the smash success of “Stir Crazy,” starring Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor.

“He finally established himself enough to have the freedom to pursue lightheartedness,” said Cade. “In all the interviews I’ve read, especially when he was talking to Black press, it came across that he was a full-bodied person. And he finally had the opportunity in his directorial work to explore that. I mean, to make an action-comedy film like ‘Uptown Saturday Night,’ who knew that was in him? It really speaks to the limitless nature of his gifts.”

In many ways, Poitier’s impact and legacy in Hollywood became bigger than any one person could sustain, which may partly explain why he receded from the screen, acting less and less frequently in the ’80s and ’90s up to his last role in the television movie “The Last Brickmaker in America” in 2001.

“He was well aware of, and I think always negotiating, this symbolic presence that he had,” said Stewart. “He was in such a rarefied space that there was tremendous symbolic attachment to everything he did, but he was also committed to continuing to work and to develop as an artist.”

“Sidney’s legacy to the people who have come after him, I would say it’s the freedom to choose,” said Cade. “They no longer had to be this perfection onscreen. People who came after him had the ability to be messy. They had the ability to be evil. They could be a villain. They could be complicated. They could not just be a foil to injustice. They could be the injustice, they could have this full embodiment of a person onscreen. When we think about his run of roles that we were all thinking and talking about, that is what his legacy means.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.