Sidney Poitier made it easy to be in the presence of greatness

It’s never easy meeting a legend.

Interviewing larger-than-life figures has always been daunting for me. At times it can be disorienting, at others a letdown.

Then there was Sidney Poitier.

I only spoke to Mr. Poitier twice — in 2000, during an interview about a documentary exploring his groundbreaking career, and a more informal encounter at a book signing a few years later.

Both times I was short of breath. My awe of him was fueled by the impression he had made on me as a youngster watching “Lilies of the Field” on my parents’ black-and-white TV. His amazing 1967 trifecta — “In the Heat of the Night,” “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” and “To Sir, with Love” — were must-sees, not only for Black moviegoers but for viewers of all colors.

As a teen, my friends and I were first-weekenders for his films, especially his comedies with Bill Cosby: “Uptown Saturday Night,” “A Piece of the Action” and “Let’s Do It Again.”

And “brilliant actor” was far from the only line on Mr. Poitier’s resume. He projected an admirable dignity and confidence that made his fans feel they were watching greatness in action. And what he represented as a Black artist who was so highly respected — who was truly Hollywood royalty — was immeasurable to me.

So it’s probably not surprising that I was so nervous in the days leading up to our 2000 interview. Even two decades later, I still remember it vividly.

Sidney Poitier, who made history as the first Black man to win an Oscar for lead actor and who starred in ‘Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,’ has died.

Poitier was promoting “Sidney Poitier: One Bright Light,” a biographical “American Masters” documentary directed and narrated by his friend and “In the Heat of the Night” co-star Lee Grant. In addition to showcasing his groundbreaking film career, the project traced Poitier from his childhood in the Bahamas through his awkward and nearly disastrous beginnings as an actor in New York, and extended into his emotional salute at the 1995 Kennedy Center Honors and his appointment as the Bahamian ambassador to Japan.

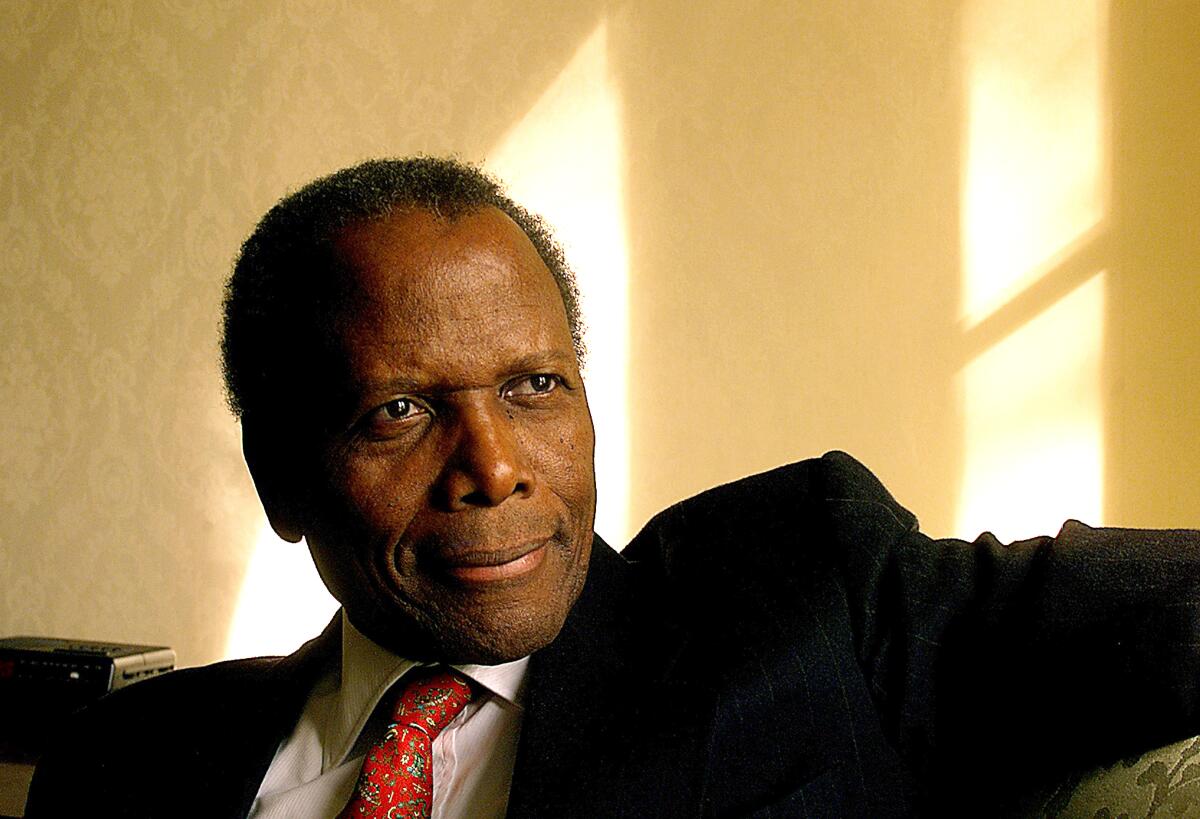

I walked into the suite at the Pasadena Ritz-Carlton that PBS had booked for a junket, tape recorder clutched in my sweaty hand. Mr. Poitier greeted me with a strong handshake. I sat opposite him, almost in disbelief that he was actually there in the flesh. He was 72 at the time, but I was struck by how movie-star handsome and youthful he still looked.

My nerves were calmed by his quiet dignity. Although he was aware of his status as a screen icon, he was more personable — and down to Earth — than many celebrities I’d met before, or have since. His smile and his voice were electric. He could not have been more polite.

As we discussed the biography, he made it clear that fame meant little to him and that he took little pleasure in being considered a cultural symbol.

“That is not the person I carry around with me,” he said. “The person I carry around is still very much alive, not in the past.”

Lee Grant’s ‘One Bright Light’ profile wasn’t an easy sell to the actor, who isn’t comfortable with the nature of celebrity. But the scope of his work and concerns are now on record.

It was that aversion to celebrity that made it so difficult for Grant to convince Poitier to participate in the project. She pleaded with him for years, and he politely but consistently resisted. But she finally wore him down.

“I have known her for many years, and as an actress, she is just mesmerizing, very gifted,” he said. “I knew that as a director, she would know how to handle it. I thought about it for quite a while, and she kept checking in. Finally, I said, ‘I’ll do it, for no one but you.’ She is a kindred soul.”

Mr. Poitier took a while when I asked him to name his favorite performance or movie. He said he was pleased with moments in “The Defiant Ones,” “A Raisin in the Sun,” “In the Heat of the Night” and “A Warm December.” Then he slowly smiled: “And ‘A Piece of the Action.’ I remember seeing that again not along ago. And I can say to myself, ‘That was it. I got close to the mark.’”

As he spoke, I resisted the temptation to look to see if my tape recorder was working. I silently prayed that it wasn’t malfunctioning.

When the PBS publicist came over to announce that our time was up, my eyes widened. Our conversation had lasted about 40 minutes, but it seemed that only a few moments had passed. I grabbed the recording and awkwardly attempted to tell Mr. Poitier how much he meant to me and how I wished we could keep talking. He said nothing, but gave me the warmest of smiles. I exhaled deeply, almost stumbling as I exited the suite.

About two years later, I was doing a story on actor Robert Guillaume. I went to Book Soup in Hollywood to cover a signing for his book “Guillaume: A Life.” Mr. Poitier was there — the two were good friends. After the reading, I hung back, trying to summon the courage to approach him. I finally went up to him: “You probably don’t remember me, but I interviewed you a few years ago and it was such an honor.”

His warm smile reappeared. “Oh, I remember you,” he said, as if we were old friends. Once again, I could barely speak.

Hearing of Mr. Poitier’s death fills me with such sadness. But I am so honored that I got to meet him, and those memories will forever live with me. When it came to spending a few moments with a true legend, he made it easy.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.