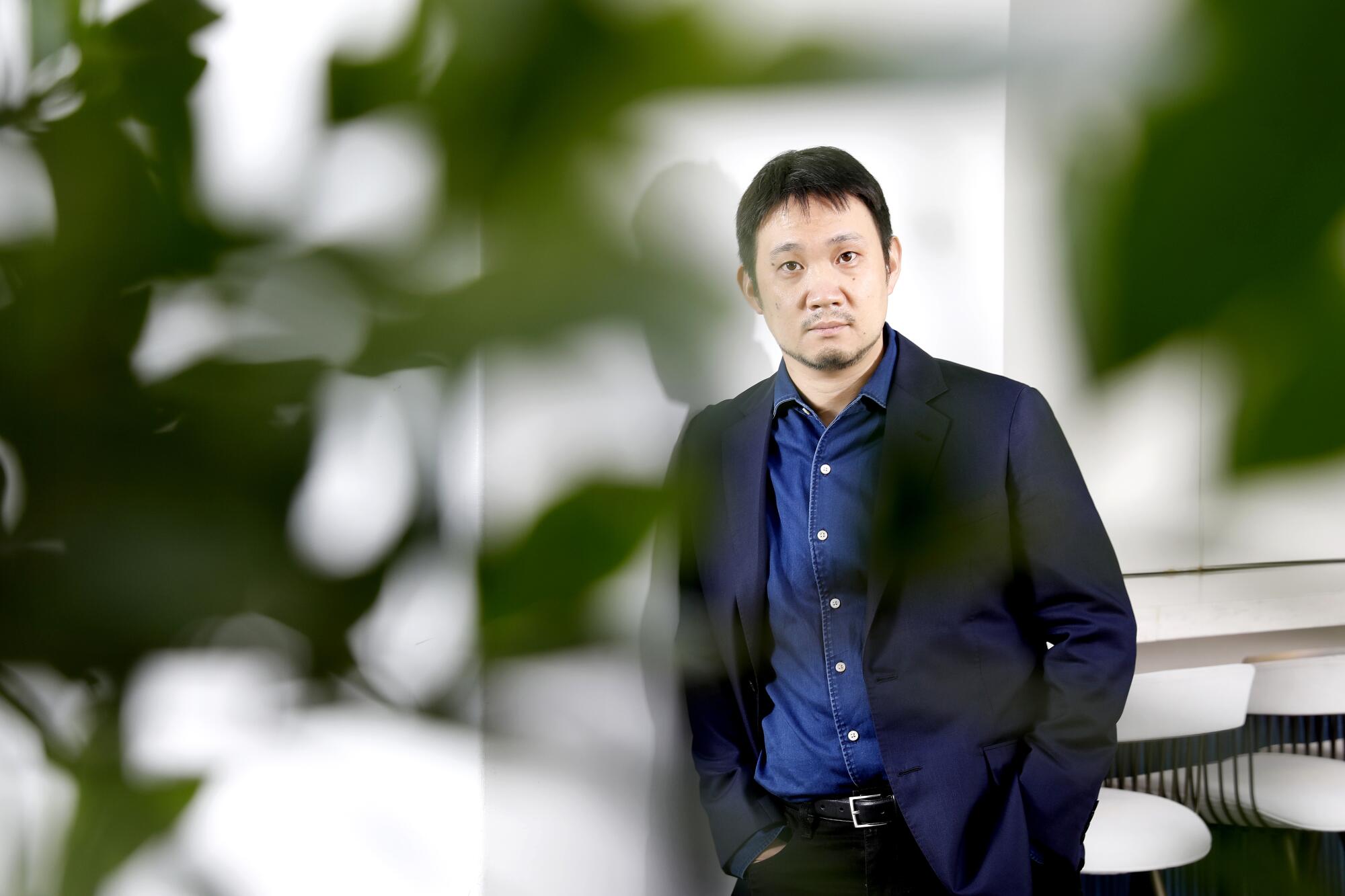

Getting behind the wheel of a moving vehicle doesn’t much entice thoughtful Japanese director Ryûsuke Hamaguchi. “I don’t consider myself a good driver, to be honest. I would rather be on the passenger side. I enjoy that.”

That confession came as he was recently speaking via an interpreter in Los Angeles. What actually revs his creative engine are the soul-bearing exchanges that can occur within the confines of an outdated but immaculately kept two-door automobile.

Hamaguchi’s critically exalted masterwork “Drive My Car,” which has been adapted for the screen from a short story of the same name by revered author Haruki Murakami, tracks the winding roads of two individuals, a rider and a chauffeur. The captain is widower and theater director Yûsuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima), who must accept the services of Misaki (Tôko Miura), a young woman working as a driver, in order to take a job directing a multilingual version of Anton Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya.” For Kafuku, driving had been a ritual of introspection. Now he must share that intimacy with another person who is also harboring deep pain.

Hamaguchi says he recognizes himself in his protagonist, a man finding in work an escape from unresolved tragedy. “In the original story the character is an actor and in the movie he’s also a theater director, and since they’re different from me in terms of their professions, I had to make them closer to me,” he explained.

This emotionally overwhelming adaptation of a Haruki Murakami short story confirms Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s standing as one of the most exciting filmmakers working today.

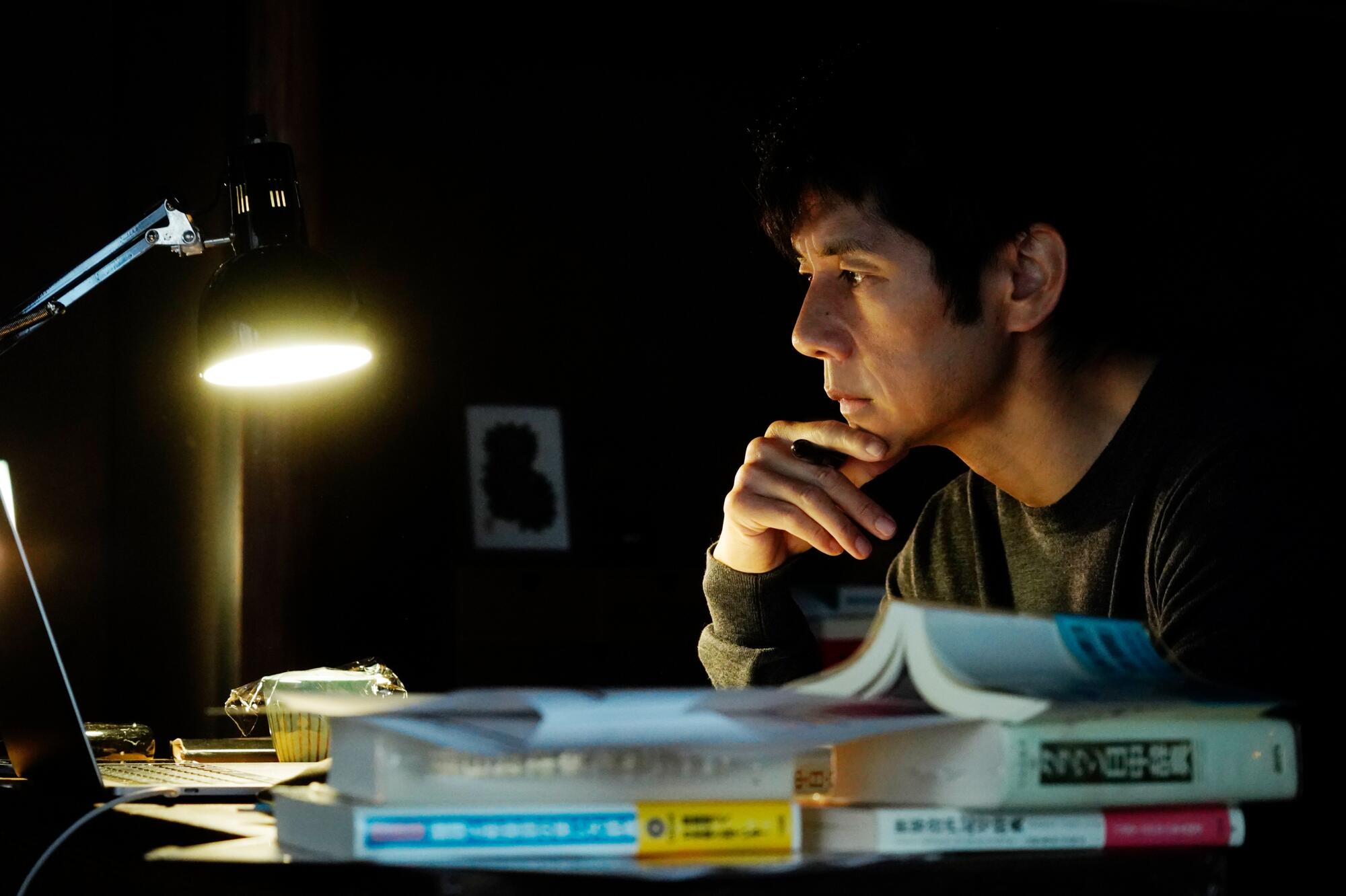

His own practices with actors informed those used by Kafuku — repeated script reading, Hamaguchi believes, helps the thespians internalize the text and decipher its multiple meanings. “I am always hoping that I will be able to capture that moment ... when the actor and the text really become connected,” he said.

“Drive My Car,” which won the screenplay award at this year’s Cannes Film Festival and is the Japanese entry for the next international feature Oscar, has been on a tear this awards season, earning best picture prizes from both the New York and Los Angeles critics organizations and even landing a coveted slot on former President Obama’s list of the year’s best movies.

Perhaps even more impressively, it’s one of two films Hamaguchi released this year — the other being “Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy,” itself a cinematic triptych of romantic bite-sized fictions.

Were you an avid reader of Murakami’s work before engaging with his writing for a film adaptation? If so, why was ‘Drive My Car’ the chosen piece of this purpose?

I have been reading his stories since I was in my 20s, but during my 30s I didn’t get much of a chance to read his books. “Drive My Car” was first introduced back in 2013 in a magazine and an acquaintance of mine recommended it. I read it and I liked it. But at the time it wasn’t realistic to think I would make a movie out of it.

But then in 2018, a producer told me, “You could adapt his short stories into a movie,” and he suggested a story of Murakami from 2018, but that, that story seemed a bit difficult to adapt. I brought up “Drive My Car” as something that we could possibly turn it into a film.

Can you describe the process of adapting this short story into a three-hour film and how the expansion changed the structure and perhaps even the themes?

I was attracted to the relationship between Kafuku and Misaki and their conversations taking place inside the car. I thought it was interesting that the relationship develops in that very enclosed space. That was the core. But the story itself is only about 40 pages long, so I didn’t think that there was enough material to create a film. I had to bring other elements from two other stories in the same Haruki Murakami collection [“Men Without Women”].

One is “Scheherazade” and the other is “Kino.” In the text, the “Drive My Car” story starts after the death of the wife, but for the movie I needed to portray the past and also the future. To depict the past and the character of the wife, I took the story from “Scheherazade,” which is the story of a woman who tells a story after having sex.

The other story, “Kino,” was used to portray the future that was not part of the original “Drive My Car” story. In “Kino,” the main character is a husband whose wife has an affair. Towards the end of the story this husband realizes that he should have faced his wife in a more proper manner.

Did Murakami provide any feedback during this time or a reaction after the film was completed?

We got permission from him, but we had very little contact. Every time I did a rewrite of the script, I’d send it to him, but there was no feedback. We invited him to a screening, but he didn’t come. So I thought, “Maybe he’s not interested in this movie.” But I learned that he did watch the movie at his local movie theater with his wife. I heard that he enjoyed it through a New York Times article. But I’ve still never met him.

Although the passage of time moving forward, often reflected in leaps of several years within a story, is a constant in your work, you rarely use flashbacks. Tell me about this narrative decision.

I don’t make much use of flashbacks because they make things too definitely descriptive, and they take away from the richness of how you want to portray something. I create this structure so that audiences can generate their own flashbacks, so I don’t have to use them. What’s happening in present time is something that you cannot really define, but if you use a flashback then you are explaining it. ... And the flashbacks only allow the audiences into a certain point in time in the past. I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to define for audiences that what’s happening now happened because of that thing that happened long ago.

The Los Angeles Film Critics Assn. spread the wealth with awards for Jane Campion, Simon Rex, Penélope Cruz and more outstanding work from 2021.

In “Drive My Car,” the car itself seem becomes a sort of temple for the protagonist, a place of solace. Do you feel this attachment is preventing him from moving on and emotionally addressing the reality of his circumstances?

Yes, for him the inside of the car is a very comfortable environment and it was a comfortable space even before the death of the wife. ... It has become a space where he feels that he can always be with his wife. So even though it’s sort of temporary, that place gives him the comfort. Then the audience realizes that’s something that he needs to let go but struggles to.

There’s one shot in the movie that I particularly love. We see the car driving and then in a brief transition the wheels fuse with the cassette reels, as if his wife’s voice recorded in the tape was fueling the car. What was your intention?

This is about the movement of rotation. I think that somewhat represents what this movie is about. That scene that you just mention is about the only flashback I used or something close to a flashback. And it shows the realm of the dream for Kafuku and his emotional state. I like that scene and this movement of the rotation of the wheel and the tape. It signifies forward movement, and yet the tape just rotates and rotates meaning that it also returns. That rotation is a representation of what this movie is about.

Considering theater has a prominent position in your work, what do you think is the relationship between it and cinema? They seem so distant in their dynamics and languages of expressions, and yet they inform each other in your dramas.

I still may not fully understand the relationship between the cinema and theater. When I asked the actors, they said, “Oh, there’s no difference between those two. It’s just the sheer level of volume when speaking that’s different.” But I think that there are many differences between them. In this movie, the description of the theater and this play is not just the mere transfer of what happens in the theater onto the screen. This is more about the acting or the performances of the theater in the realm of the film, which happens in front of the camera. That’s how it was depicted in the film.

In regards to acting, and how actors embody characters to materialize inner worlds, how do you feel these two dramatic mediums differ?

I find acting is kind of a mysterious thing. Acting is something that’s made up or something that is a fiction, but when a performance is superb, then it becomes something beyond fiction, and you can’t believe it’s based on something that’s not real. The film itself is something that records what’s happening, but the acting has the power to change the fiction into something that you can believe using the performers’ own bodies.

This could happen in both the film and the theater, but in the case of theater, the condition is that whether you’re seated at the very front row or the back row, what the audience is seeing needs to be at the same level, it cannot be too different. And so that is why in the theater, the actors tend to be very exaggerated or overact. That may cause audiences not to really believe in the performances, but in film, because this acting happens in front of the camera, you don’t have to overact. They can perform more sensitive elements of what they want to express. Whether it’s theater or cinema, what you’re trying to achieve may be the same, but I find the medium of film is better suited for my purposes to do that.

In the film, Kafuku works with a multinational cast that communicates in a variety of languages, and yet through his method he is able to bring them together on a sensorial level where spoken words become secondary to what they feel. Can you explain your views on this fascinating approach?

Words and languages are important, especially the mother tongue, because it’s really associated with your body, the physical being. In the theater the actors tend to act in an exaggerated manner, showing off their acting, but in this multilingual theater you cannot understand the words, so you cannot take meaning from the words, because you don’t understand them. You understand the sound and you try to process understanding through sound, which means that the actors tend to react and respond to the real being inside the body rather than surface. They really need to listen, and they really need to see what the other actors are doing. Rather than trying to act on their own, the actors depend on trusting the other person and reacting to them when performing.

It’s important that the camera captures these actors reacting to hearing the other actors’ sound and watching as they move. In order to realize that we have this rehearsal process, and we do this reading many times. When we are doing that, the actors are looking at the script in their own first language, and then they’re listening to the others talking through the sound. By repeating this process, they’ll come to a point when they hear the sound that they can understand the meaning, even though they don’t understand the language, but they know what’s being said, because it gets embedded in their memory. When they are performing, they can see invisible subtitles in their mind. Getting to that point will allow them to perform solely based on the interaction with the other actors.

Watching your movies, I’m often affected by the way the dialogue can be incredibly piercing to the recipient. The sincerity in their words hurts, and it’s very powerful to witness their effect.

In general Japanese people wouldn’t say some of the dialogue in my movies. In Japanese culture, expressing your emotions in a very honest and straightforward manner is not common. Japanese people are not used to doing that. At the same time letting the characters say something that’s very honest and direct is something that’s necessary for me in my films.

There are moments people might think are painful, but that’s necessary in order to portray someone who is presumably living a good life or a life that has improved. In life, even if you achieved something better for yourself, there’s still always the pain. Like when you really love someone, there is always a chance that you will lose that person, those two things come as a set. When you want something, there’s also a time when you cannot get it. And even if you get that something you wanted, there is a possibility that you will lose it. In my movies, I like to be able to portray that just having a better life is not always simply better. There’s also pain that comes along with it.

Los Angeles Times film critic Justin Chang’s best movies of 2021 include ‘Drive My Car,’ ‘The Power of the Dog’ and ‘The Green Knight.’

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.