From the directors of “RBG,” a new documentary about Julia Child that reveals the sensual, romantic side of the famous chef.

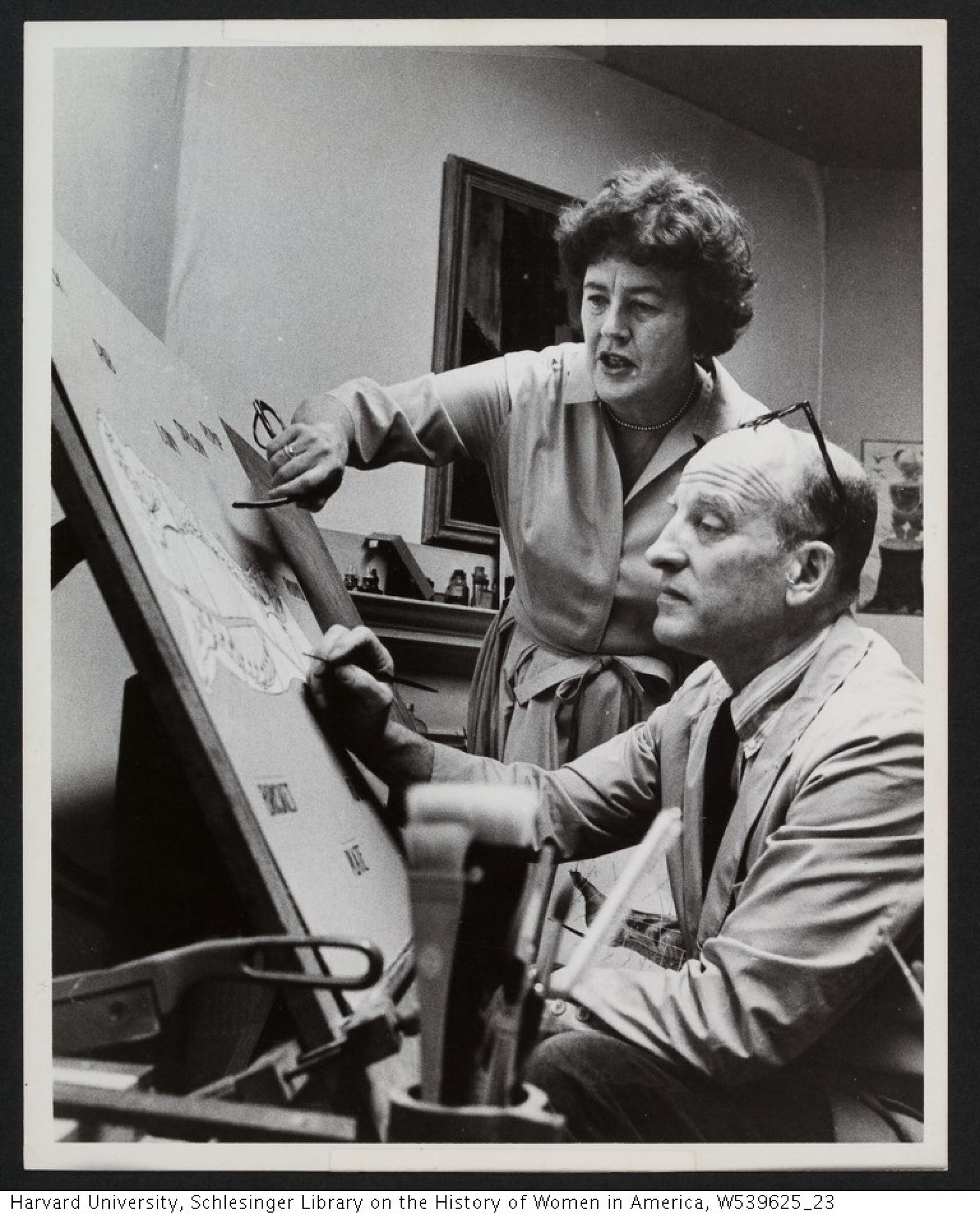

While Julia Child was busy teaching her loyal public television viewers how to make boeuf bourguignon, her husband could be found crawling at her feet.

From the floor of “The French Chef” set, Paul Child would hold up signs to help his wife during filming. They called them idiot cards. “Move on!” “Wipe brow!” “Don’t forget mushrooms!”

Julia was 51 when she started filming her cooking show at WGBH in Boston, and Paul, 10 years her senior, continued assisting her from the ground up well into his late 60s.

This was not always their relationship dynamic. Paul had already lived in France and Italy, was a black belt in judo and relished fine cuisine when they met in 1944. Julia, who had a cosseted upbringing in Pasadena and a boarding school education in Marin County, had never lived abroad, though she’d worked as a copywriter in New York after graduating from Smith College. Against her wealthy family’s wishes — and after turning down a marriage proposal from Harrison Chandler, son of L.A. Times publisher Harry Chandler — she joined the Office of Strategic Services, the United States’ intelligence agency during World War II. After a period in Washington, D.C., she was sent to Sri Lanka where she encountered Paul.

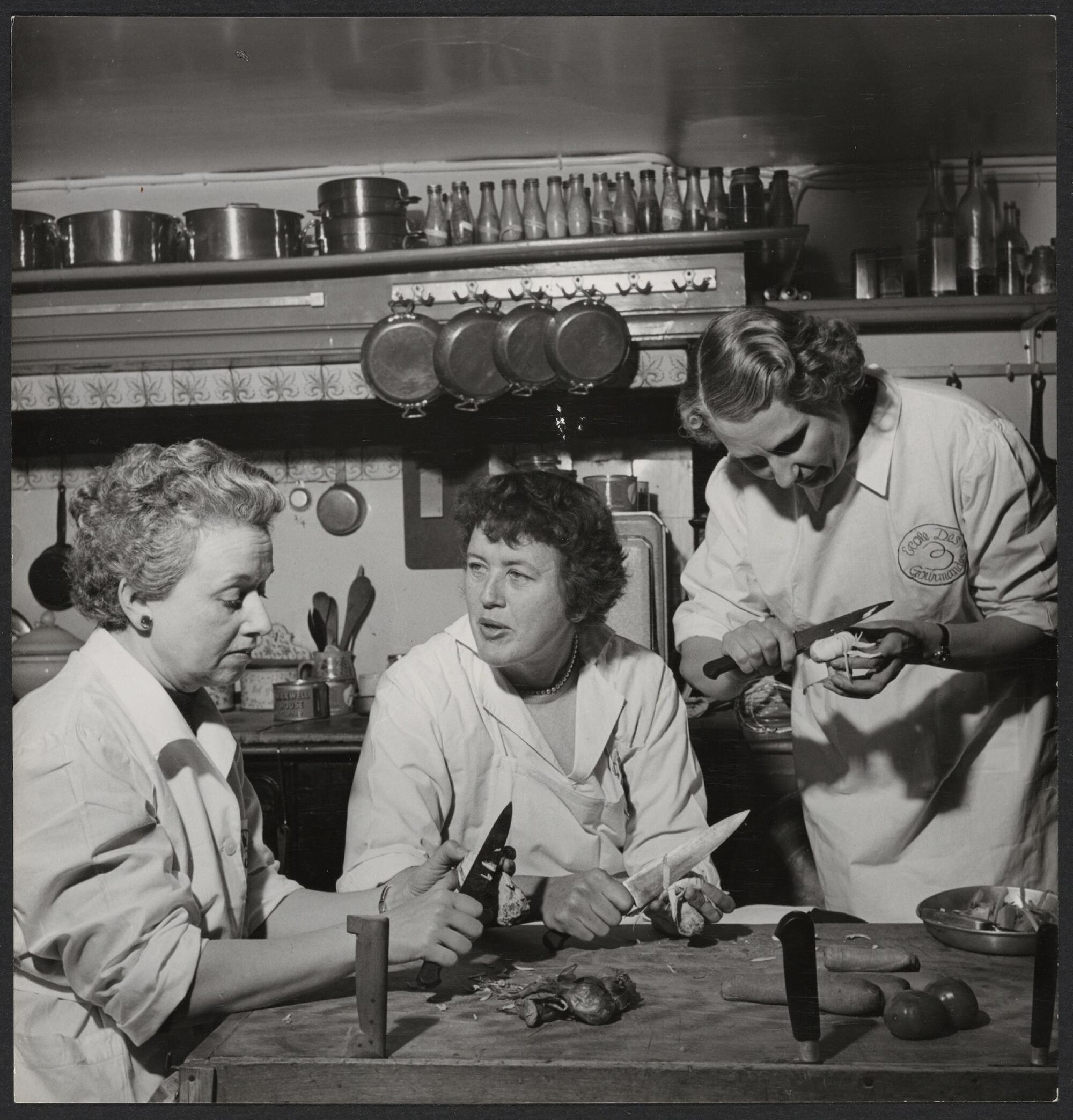

At first, he was not impressed by Julia. In letters to his brother, he described her as “an extremely sloppy thinker” with “an unbecoming blond mustache” who was “unable to sustain ideas for long.” Yet as they fell in love he took it upon himself to open her eyes to the world, first in China when they were stationed in Kunming, then after the war in France, where they moved in 1948. The first day they stepped off the boat in France he brought her to La Couronne, which after more than 600 years in business was the country’s oldest restaurant, and ordered for her what she came to call “the most important meal” of her life.

“I often compare their relationship to ‘My Fair Lady,’ where she’s the willing student like Eliza Doolittle and he’s the sophisticated older man who tutors her in culture and art and politics,” says Alex Prud’homme, Julia’s grand-nephew, who has written three books about her. “Paul was the leader of their relationship during the first half, and when he retired, everything flipped. It was very intentional. He described himself as the iceberg beneath the water, where you just see the tip, but he’s playing this massive role as the ballast — and you can’t have one without the other.”

The Childs’ marriage is at the heart of a new documentary, “Julia,” which began rolling out in theaters earlier this month. The movie was co-directed by Julie Cohen and Betsy West, the filmmakers behind the 2018 portrait of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, “RBG.” Like “Julia,” “RBG” also emphasized the power balance between the late Supreme Court justice and her husband, Marty, a tax attorney who lobbied the Clinton administration so aggressively on her behalf before her 1993 nomination that Ruth jokingly referred to him as her “campaign manager.”

“I think the existence of the supportive, loving, feminist husband playing a role in the success of these two women is not a coincidence,” Cohen says of her film subjects. “And it’s not just that Paul helped out and was on set. It’s that he was willing to support and cheer Julia on in decisions that might sometimes make his career take a back seat to hers. He got that she was going places, and wanted to help her get there — just like Marty Ginsburg did with RBG.”

After the commercial and critical success of “RBG,” it became clear that there was a “huge appetite for more stories delving deeply into the historic lives of groundbreaking women,” Cohen says. The directors considered a number of potential female icons, but when they were approached by Child biographer Bob Spitz about making a documentary,

their interest was piqued.

“We were on a cross-town bus considering the idea, and we started talking about food before Julia: TV dinners, Jell-O salads, tuna casseroles,” West recalls. “We started thinking, ‘Well, why is it that in the ‘70s and ‘80s, people really started cooking?’ And we feel a lot of it had to do with Julia. She sparked something that so changed the culture.”

She also changed the television landscape for female creators, the directors say. Before “The French Chef” debuted in 1963, “women were expected to be in the background on TV, being pretty and perky and dancing around the refrigerator in ads,” West says. “Julia was not in that mold.”

The filmmakers scoured through hours of programming held by WGBH for television footage of Julia. But the most illuminating material came from the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University, where her diaries, letters and photographs are stored in an archive.

In the final year of her life, Julia read aloud from many of those letters while putting together her memoir, “My Life in France,” with the aid of Prud’homme.

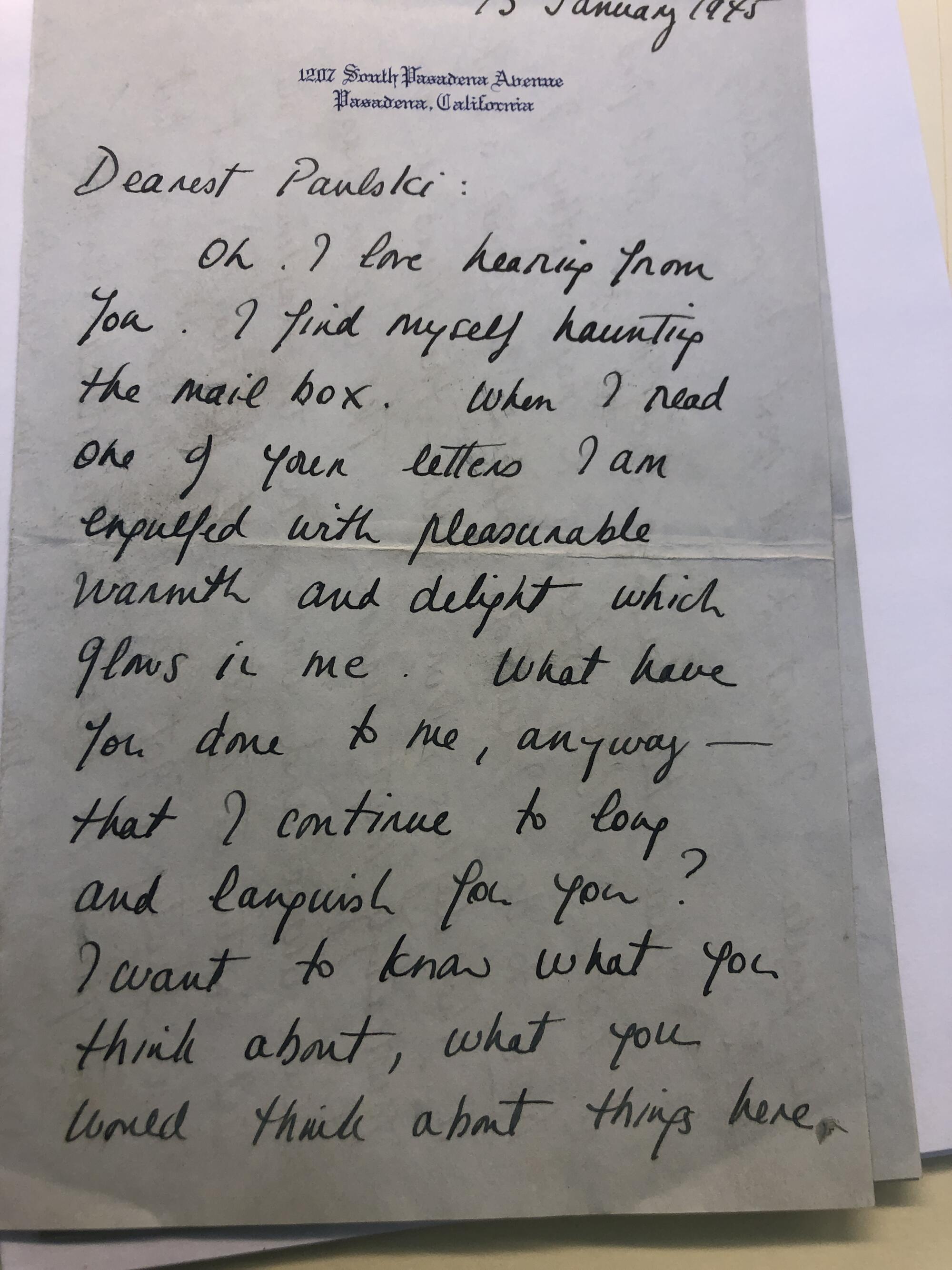

“Julia’s letters were short — like a page or two — typewritten with lots of capital letters, exclamation points and a big heart at the end,” Prud’homme says of his great aunt’s correspondence. “But she liked Paul’s best. His were very beautiful — like five, six, seven pages with calligraphy and all sorts of journalistic details. And Paul and Julia would write on each other’s letters and comment, like, ‘I totally disagree with her on this!’”

The letters — many of which are quoted from in the documentary — reveal a sentimental, passionate side of Julia, who used proper, formal mannerisms on her show.

“Dearest Paulski,” she wrote to Paul in 1945, “Oh. I love hearing from you! I find myself haunting the mailbox. When I read one of your letters, I am engulfed with pleasurable warmth and delight which glows in me. What have you done to me, anyway — that I continue to long and languish for you?”

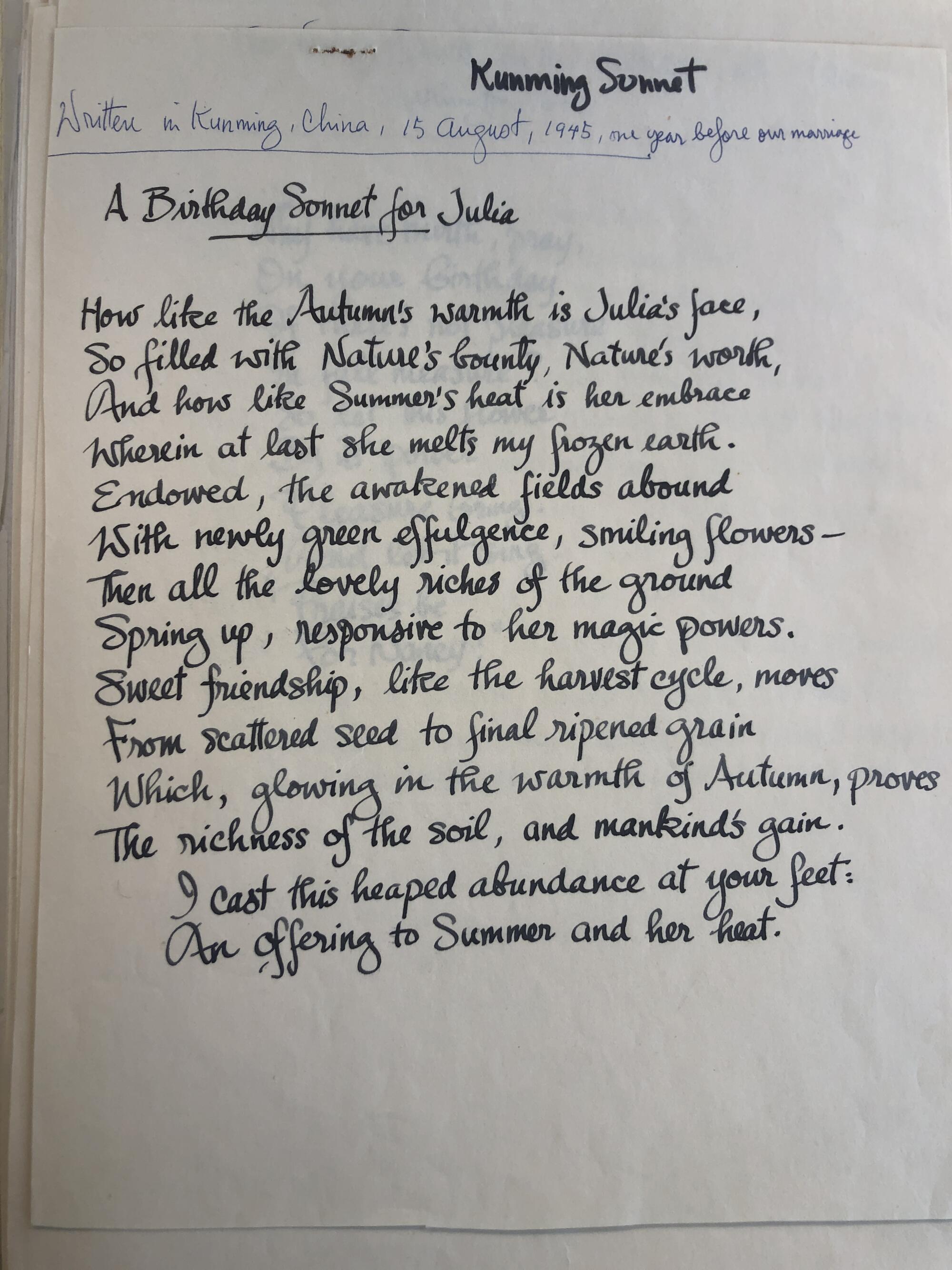

Paul’s messages were similarly romantic. In August of that year, he sent her a sonnet for her 33rd birthday:

How like the Autumn warmth is Julia’s face,

So filled with Nature’s bounty, Nature’s warmth,

And how like the Summer heat is her embrace

Wherein at last she melts my frozen earth.

Later, Julia would serve as a muse for his photography. In 1948, the couple moved to Paris after Paul was assigned to be an exhibits officer with the U.S. Information Agency. Julia spent her days learning to cook at Le Cordon Bleu, but the pair would typically spend their afternoons walking around the city — journeys that Paul documented with his camera. Other images from that time period, taken inside their residences, are even more intimate: In one, Julia’s nude body appears in silhouette against a curtain.

“I don’t know how she’d feel about that being in the documentary,” Prud’homme says with a laugh. “But at the time, she was an anonymous, diplomatic wife who loved to participate in Paul’s photography. It’s quite a subtle, sensual photograph. He caught great glimpses of this person we now know as a celebrity just laughing, completely relaxed.”

In public, however, the couple wasn’t particularly affectionate. Phila Cousins, Julia’s niece, first got to know her aunt and Paul while she was a student at Radcliffe. Over biweekly dinners at the Child home in Cambridge, Mass., Cousins says her relatives weren’t known for being “lovey-dovey.”

“But they clearly had a very strong bond together,” she continues. “She would pat his hand. Their relationship was definitely sexual — there was absolutely no question about that — but they weren’t huggy and kissy.”

While Julia had a reputation for being extroverted — warm and open — those who knew them say Paul was more difficult to get close to. He could be pedantic and was the type to correct your spelling or grammar, notes Cohen.

“I think everyone accepted Paul because he was part of the team,” acknowledges Cousins. “Paul was a real stickler for precision in thinking and talking. He said I had a first-class mind, but I was totally untrained. He wanted me to be much more specific in my word usage. It was a little daunting, at first, going to dinner there as a 17-year-old just getting to college.”

But Julia remained loyal to him until his death in 1994, which followed years of health struggles. Two decades prior, he went in for a heart bypass and during the operation, his brain was starved of oxygen. Afterward, Prud’homme says, Paul was left with “mental scrambles” that made it hard for him to express himself.

“So when I was coming of age, he was moody,” the nephew admits. “He could be wonderfully funny and entertaining when he was feeling good, but he could be a simmering volcano.”

Though Paul recovered — he lived until age 92 — “he was basically transformed,” says cookbook author Anne Willan, a longtime friend of the couple who founded La Varenne cooking school in France and was also one of Julia’s cooking co-instructors. “He was this witty, amusing, erudite, worldly man — the leader in Julia’s career and certainly gastronomic knowledge. He was Julia’s manager, and very much the power behind her on the stage. But after this terrible surgery, he was never the same person again.”

Julia tended to Paul dutifully, nursing him as she carried on writing cookbooks and hosting television programs. She always felt a strong obligation to be a wife, and in the early days of their marriage in France, she joked about returning home to Paul at lunch to perform what she called the “Three F’s: feed ‘em, f— ‘em and flatter ‘em.”

“You have to remember that she’s a product of her times,” says Cohen, referencing the “Just a Housewife” ethos propagated on “The Donna Reed Show” in the 1950s.

“And remember, she was also trying out all of these recipes on Paul,” adds West. “It wasn’t just that she was cooking a romantic meal for him. He was her taste tester.”

Though Julia eventually went on to become a vocal advocate for Planned Parenthood, she recoiled from identifying herself as a feminist. Despite this, the filmmakers feel she was one: “If you define a feminist as a person who thinks that women have the right to realize themselves separate and apart from the men in their lives, she was a feminist,” says Cohen.

“Look, she believed in women,” West says. “She believed in women’s abilities, women’s agency and their right to exist in the world and to find their own passion, which is what she did.”

Following Paul’s death in 1994, she starred in four more TV series and continued to publish cookbooks. She even got a boyfriend — a “wonderful guy who they’d known during World War II who lived in Cambridge,” says Cousins. “She would say: ‘It’s really nice to have a chap around.’

“She was never one to talk about negative feelings. Her view was: You keep moving forward. But she was very sad without Paul. I think she felt, in some ways, like half of her was missing. He was the love of her life.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.