When Adam McKay thinks back on his many comedic collaborations with Will Ferrell, the one that feels most in tune with 2021 may not be what you’d expect.

“I would say the most prophetic turned out to be ‘Step Brothers’ — that’s the most like the world we’re living in,” McKay shared during a recent sit-down at his Los Angeles home.

“‘Step Brothers’ was a living cartoon when it came out, [and now] it’s literally true. When you see giant grown-ups screaming and kicking over furniture because they have to wear a mask, that’s actually more preposterous than ‘Step Brothers.’”

McKay was discussing how current events caught up with — and in many ways overtook — his idea for the upcoming Netflix-produced comedy “Don’t Look Up.” The contemporary disaster movie may not feature Ferrell, but its all-star cast rivals that of “The Towering Inferno” and “The Poseidon Adventure,” and its sharply honed satire is after more than apocalyptic thrills. It’s the next step in McKay’s ongoing cinematic evolution, which has already produced the Oscar-nominated “The Big Short” and “Vice.” (The filmmaker earned an adapted screenplay Oscar for the former.)

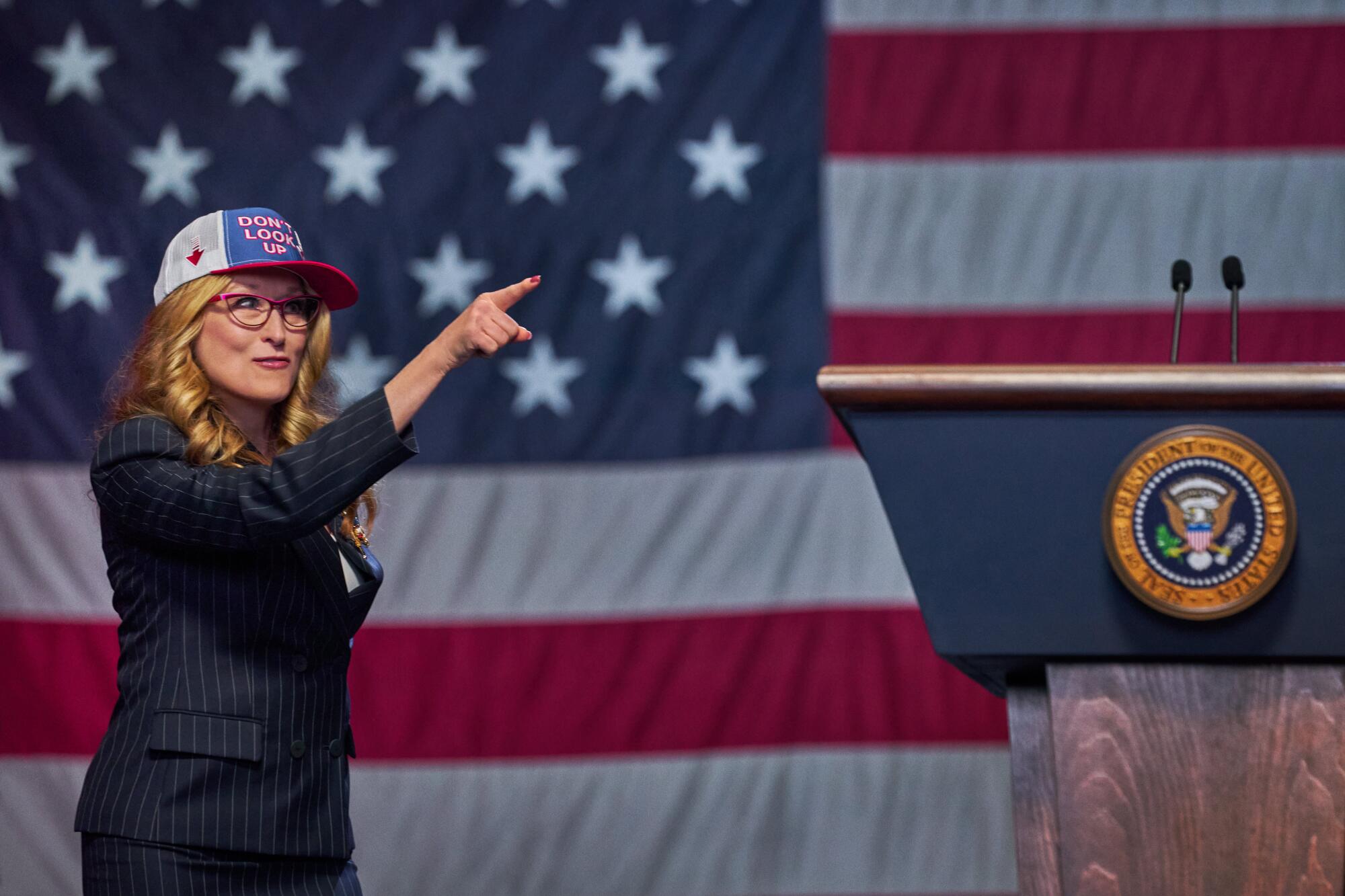

In “Don’t Look Up,” a pair of scientists (Jennifer Lawrence and Leonardo DiCaprio) discover a giant comet, which will collide with Earth in six months and destroy life as we know it. As the duo struggle to bring wider attention to this Earth-ending dilemma, President Janie Orlean (Meryl Streep) only becomes invested when it’s politically expedient, aided by the intervention of tech billionaire Peter Isherwell (Mark Rylance). The cast also includes Jonah Hill as Orlean’s son and chief of staff, Cate Blanchett and Tyler Perry as TV talk show hosts, along with Rob Morgan, Ariana Grande, Timothée Chalamet, Melanie Lynskey, Kid Cudi, Himesh Patel and more.

With the film set for release in theaters Dec. 10 and on Netflix Dec. 24, McKay opened up about the equally disturbing and delightful project he classifies as “absurdist comedy horror” and how to make fun of the world while trying to very much be a part of it.

First of all, why a comet? How did you come to have that be the catalyzing event of the movie?

I knew for the past couple of years the story in human experience is the climate. It’s maybe the biggest story on planet Earth in 66 million years since the Chicxulub asteroid hit. So I have been trying to think of how to do a movie that deals with that. And I thought of like five or six different movie ideas. One was very dramatic and epic. One was a little bit more like an M. Night [Shyamalan] movie with kind of a twist. And I just had all these ideas. And then my friend David Sirota [who shares a story credit on the film], I think he had a tweet or something where he’s just like, “the comet is coming and no one gives a s—.”

He was talking about the climate crisis. And I kept thinking about that, and maybe it’s that naked and that simple. If we had that sense of impending doom — because we can all get our head around that, if there really was a comet coming — I’m not sure we would know how to handle it. We’re so broken right now. And then I started realizing, “Oh, this is it.” It’s a very simple entryway, but it’s funny.

On its face, this is an allegory for climate change, but it actually reveals itself to be about the cultural and political moment we’re in, where people can’t agree on basic facts and the simplest of things. When did this other aspect appear?

We were scouting [locations to film] in Boston, and I’m an NBA fan, so I was watching the Jazz game [on March 11, 2020,] and the referees said the game was canceled for COVID. The next day, we still scouted — we might have all been wearing masks already — but then we’re like, “We gotta get out of here.” We went home, and then it was like six months of just [being] at home like everyone. ... The whole time, I’m like, “Do you still make this movie? Like, did the movie just happen in reality?”

And I just didn’t touch the script for like five months. Then I was like, “All right, let’s go read the script.” And I was amazed to see that the script actually isn’t about climate change. It’s about how our lines of communication have been shattered and broken and profitized and manipulated. And that actually the engine of all the farcical comedy is that — and it totally still works. I checked in with Jen Lawrence and Leo and a couple of the cast, and I’m like, “I’m reading this, and I actually think it tells a whole different story, which was really the cause of why we haven’t been doing anything about climate change.”

And they all went back and read it, and they’re like, “Oh, we gotta do it more than ever.” So that happened very naturally. But the only thing I did do — the reaction to the pandemic was 50% crazier than the script — so I did have to go back in the script and pull some threads and make things even a little crazier. Once the president of the United States has gone on national TV and floated the idea of ingesting bleach, you’re in a different realm. ... Reality was getting ahead of me.

I’m assuming the standard line you’re going to hear is “Meryl Streep is playing Donald Trump,” but it’s actually not nearly as clear-cut as that. How did you pitch the character to her?

If you actually did a representation of Donald Trump in a movie, you kind of wouldn’t have a movie. The closest I can think of that I’ve ever come to would be Brick Tamland in “Anchorman,” where Brick kind of didn’t live in the movie. We actually did one take where Brick just pointed and said, “Look, a camera.” We almost put it in the movie. That’s kind of Donald Trump; it’s impossible for him to live in a narrative.

What I wanted to do with Orlean, and what I talked to Meryl about, was I wanted her to be a kind of a stew of all the disastrous presidents we’ve had, because she’s much smarter than Donald Trump. She’s much more savvy. So she’s kind of a mixture — definitely of Donald Trump, in how narcissistic and self-serving and shortsighted she is, but there’s also plenty of Bill Clinton in there, as far as the double-talk and the polish. There’s plenty of George W. Bush, in the sense that she’s utterly underqualified for the job. There’s a little pinch of Obama, his kind of smooth celebrity thing. Plenty of Ronald Reagan, empty suit performative kind of stuff. So it’s a little bit of all of it. That’s why we put the picture of her hugging Clinton in [the movie].

And the example I gave her — it’s Meryl Streep, so you know she’s going to run with [it] — was “it’s kind of like Suze Orman,” in the sense that Suze Orman’s not dumb, but she’s definitely a little hacky and a little false, but she knows her way around some things. So Meryl kind of took that, filtered it, put a little bit of Long Island in there and then we kind of kicked it back and forth, and you end up with President Orlean.

In the character of billionaire Peter Isherwell played by Mark Rylance, with his faux benevolence masking a hardened ruthlessness, you are making fun of the leaders of Big Tech. How do you reconcile that with the fact that you’re making the movie for Netflix?

Well, I don’t consider Netflix as they exist now — there’s not really one of those supervillain oligarchs at the wheel. Netflix is definitely part of that landscape, but they’re not like Facebook. And [my production company has] a first-look deal with Apple. If you live in this world, you’re going to bump into this world. It is our world. It’s kind of impossible to get up in the morning and not bump into it. But my experience with them, and I would say the same thing for Twitter, like that guy who runs Twitter — do I think Twitter isn’t just focused entirely on profits? No, of course they are. But they seem to at least kind of try.

I think what we’re doing with Isherwell is closer to Facebook; it doesn’t seem to be trying at all, and Chevron and Shell and a lot of that stuff that’s making zero effort and is actively malignant. But your question is a funny one because every aspect of the movie kind of fits under that [topic]. Like, how do you reconcile yourself with being paid probably a hundred times more than you should be paid? How do you reconcile yourself with sometimes getting in a gas-powered car? I think the only answer to that is to move to the Orkney Islands, which I’ve looked into.

Especially with these last three movies, are you afraid they’re ever too on the nose, that there’s an issue of preaching to the choir? Do you feel a movie like “Don’t Look Up” will actually reach any people whose minds you might change? Is that what you even want from this?

Absolutely. All these movies are meant to be seen by the people that you want to see them. We’ve done test screenings, and they identify people’s political leanings on the [responses]. We knew what we were doing with “Vice.” We were going to step into a country that’s just been marketed and misinformed into this divide that probably is impossible to breach when you overtly talk about it. But ... at least it was made, it was out there. And also a bit of it is as an elegy for America, which was obviously coming apart.

In the case of this, this is much closer to “The Big Short.” It’s meant to play for people that may not believe in climate change. And it seemed to in our test screenings. Comedy is very powerful in that sense. The people that seem to really be hit by it the most are a straight-ahead moviegoing crowd that’s really taking it on the chin. And I was really happy with that in the test screenings.

Is that one way in which the global reach and the algorithms of Netflix might be a real benefit to the movie? It can push the movie in front of people who otherwise might not watch it.

That’s specifically why we chose Netflix. We had a couple of bidders for the movie, and at the end of the day, the reason we did it was because this one is entirely meant to be shown to as broad an audience as possible.

Do you consider this an act of political expression? Do you see making this movie as a piece of activism?

That was the intent. The simple, raw idea behind it was we have seen 10,000 movies where you always see [the heroes] reach their lowest point at the end of the second act — Thor is not going to save the day, or they’re not going to put out the fire — and they always solve it. And I do think there’s a legitimate power to that, that sort of narrative repetition.

Then you hear people say about the climate crisis, “Oh, we’ll figure it out.” I think Elon Musk was quoted as saying, “Technology will solve it.” And it’s like, “Hey, motherf—, you got to actually do it.” You can’t just say, “It’s going to end.” That reeks to me a little bit of the sense like we’re living in a movie. Like we just think that third acts always work out.

The part of the movie that I hope has a little wisp of some degree of activism — I don’t know if it will or not, it is ultimately just a movie — but it is that third act. I hope it jolts. I hope it surprises. I hope it gives feelings to some of the crowd they haven’t had before. If at least 8% of the audience feels like that, then the whole thing’s been worth it.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.