Pauli Murray knew the history books wouldn’t be kind to their legacy. Born Black, queer and assigned female at birth in 1910 — decades before the Stonewall uprisings and the March on Washington, and before women had the right to vote — the lawyer and advocate who fought Jim and Jane Crow-era discrimination had already experienced marginalization and erasure in life. Surely death would be the same.

But to Talleah Bridges McMahon, co-writer and producer of the documentary “My Name Is Pauli Murray,” which is now playing in theaters and launches Oct. 1 on Amazon Prime Video, Murray had other plans.

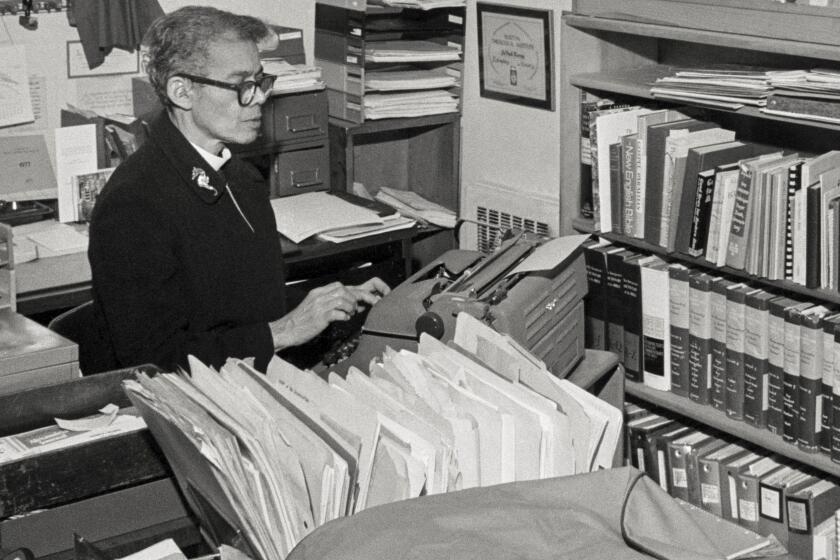

“I think Pauli wanted to be known,” she says, detailing just how robust yet curated Murray’s archive at Harvard’s Schlesinger Library is, totaling over 135 boxes. Having delved deep into the records searching for the best elements to help tell Murray’s story for a broad audience, McMahon sensed “a faith or trust at play” in Murray’s writings. Perhaps the world around them may not have recognized the fullness of their brilliance, but generations to come would.

Murray’s desire to be known wasn’t about vanity. They just wanted to be understood by a world hell-bent on misunderstanding. They wanted America to fulfill its promise of equality and freedom for all, and for the history books to accurately reflect how such a promised land materialized out of the mind of one of society’s most marginalized.

“My Name Is Pauli Murray,” then, is more than just a film that tells the story of someone who should be, as McMahon says, “celebrated in the ways we celebrate John F. Kennedy or Martin Luther King Jr.” It’s a reclamation of a broader historical record that erased such a pivotal figure and a call to action to uncover the stories of countless others whose import has been lost in the annals.

The documentary “My Name Is Pauli Murray” explores the life of the pioneering African American civil-rights activist, lawyer and priest.

Directed by Julie Cohen and Betsy West, the Sundance Film Festival-premiered “My Name Is Pauli Murray” is a transformative recounting of the life of a pioneering attorney, activist and priest. The pair, who also recently unveiled a documentary on Julia Child at the Telluride Film Festival, discovered parts of Murray’s story while in production on their Oscar-nominated doc “RBG,” which focused on the life and career of the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

It was in the course of interviews with Ginsburg before her death that they learned of Murray’s influence on the legal icon. Upon further research, Cohen and West, along with producer McMahon, questioned how such an important figure could have such little name recognition: Why didn’t they know who Pauli Murray really was?

“I’d heard Pauli Murray’s name in the context of feminism but was floored that I hadn’t really known that Pauli was actually instrumental in so much more,” says McMahon.

The Baltimore-born, Durham-raised polymath’s accomplishments and social justice efforts are vast. Fifteen years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus and 17 years before the Greensboro sit-ins, Murray was challenging racial segregation.

Murray penned a law school paper that first outlined a then-radical idea that has since quietly reshaped the legal landscape for women, queer people and people of color. Having determined that separate accommodations for Black and white people would never be equal, contrary to the prevailing laws of the time, Murray encouraged civil rights lawyers to instead challenge state segregation laws as unconstitutional.

A decade later in 1954, Murray’s approach was the basis of the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education case that overturned segregation in schools. Then in the ’70s Ginsburg used the same principle to successfully argue against sex discrimination. Quite literally, almost every significant civil rights ruling of the last 70 years can be traced back to Murray, including marriage equality.

Moreover, Murray was the first person of color to receive a JSD from Yale Law; one of the first Black writers at the noted MacDowell Colony, alongside James Baldwin; and the first Black “woman” Episcopal priest. They also helped found the National Organization for Women in 1966, having coined the term “Jane Crow” to describe the unique oppression Black women of the period faced.

Murray’s role in the collective history of this country’s sociopolitical movements, however, hasn’t been as well documented as others from the time period. Racism, sexism and homophobia likely have something to do with that, but it’s the impact of such erasure, McMahon says, that can’t be overstated.

“The result is that, if you’re a person of color, if you’re queer, if you’re a woman or from [another] marginalized community in society, it gives the impression that people from your community don’t have any value,” she continues, “that you’ve been erased because there’s nothing worth noting about you. It gives people a pretext for thinking that people like you don’t matter.”

Therein lies the importance of unearthing the historical record of queer trailblazers, says Channing Joseph, a journalism professor at the University of Southern California and author of the forthcoming “House of Swann: Where Slaves Became Queens.” Similar to “My Name is Pauli Murray,” the book uses archival sources to tell the story of the world’s first self-proclaimed drag queen, a man born into slavery named William Dorsey Swann.

A wide range of narrative and documentaries highlights to watch for at the first virtual Sundance Film Festival.

“It’s spiritually so powerful to be able to connect with somebody that you recognize as like you in some way from the past,” says Joseph, who uses he and she pronouns interchangeably. “It makes you feel not only seen but also that you’re not an anomaly.”

Considering the ways marginalized identities have become political talking points — like ahistorical, conservative messaging that wrongly asserts transgender and gender expansive people didn’t exist in times before these, for example — knowing the historical challenges and triumphs of folks from excluded communities provides a crucial counterpoint.

Additionally, such historical context helps extend the lineages of contemporary communities. For example, to know that Murray struggled with their gender identity at a time when words like “transgender,” “gender nonconforming” and “nonbinary” weren’t part of the cultural lexicon — while they were shaking up the status quo in so many other ways — helps situate the current sociopolitical fight of gender challengers and transgressors as part of a long legacy. (Though Murray did not identify as nonbinary or transgender, in an effort to recognize their gender journey — which rebuffed conventional, binary thinking of the time — activists and historians have encouraged use of gender neutral, or they/them, pronouns for Murray.)

“The more we can unearth those stories and make average people who don’t read history books aware that folks like us existed is psychologically important,” continues Joseph. “Knowing that you’re part of a history and because of that, you have something to be accountable to, a tradition to join and something that you too can leave for the future is vital.”

For Noelle Deleon, knowing the history of Black LGBTQ+ pioneers, especially Black trans women, has been life-altering. The Houston-based interdisciplinary artist is founder of the Femme Queen Archives, an effort sponsored by arts organization Black Trans Femmes in the Arts that preserves the legacies and honors the influence of “femme queens” in the once-underground LGBTQ+ ballroom scene and broader culture.

“I never understood myself in the world until I started studying femme queen performance and going back into the history of Black trans women in the world,” she says. “It’s been the key to my biggest awakenings.”

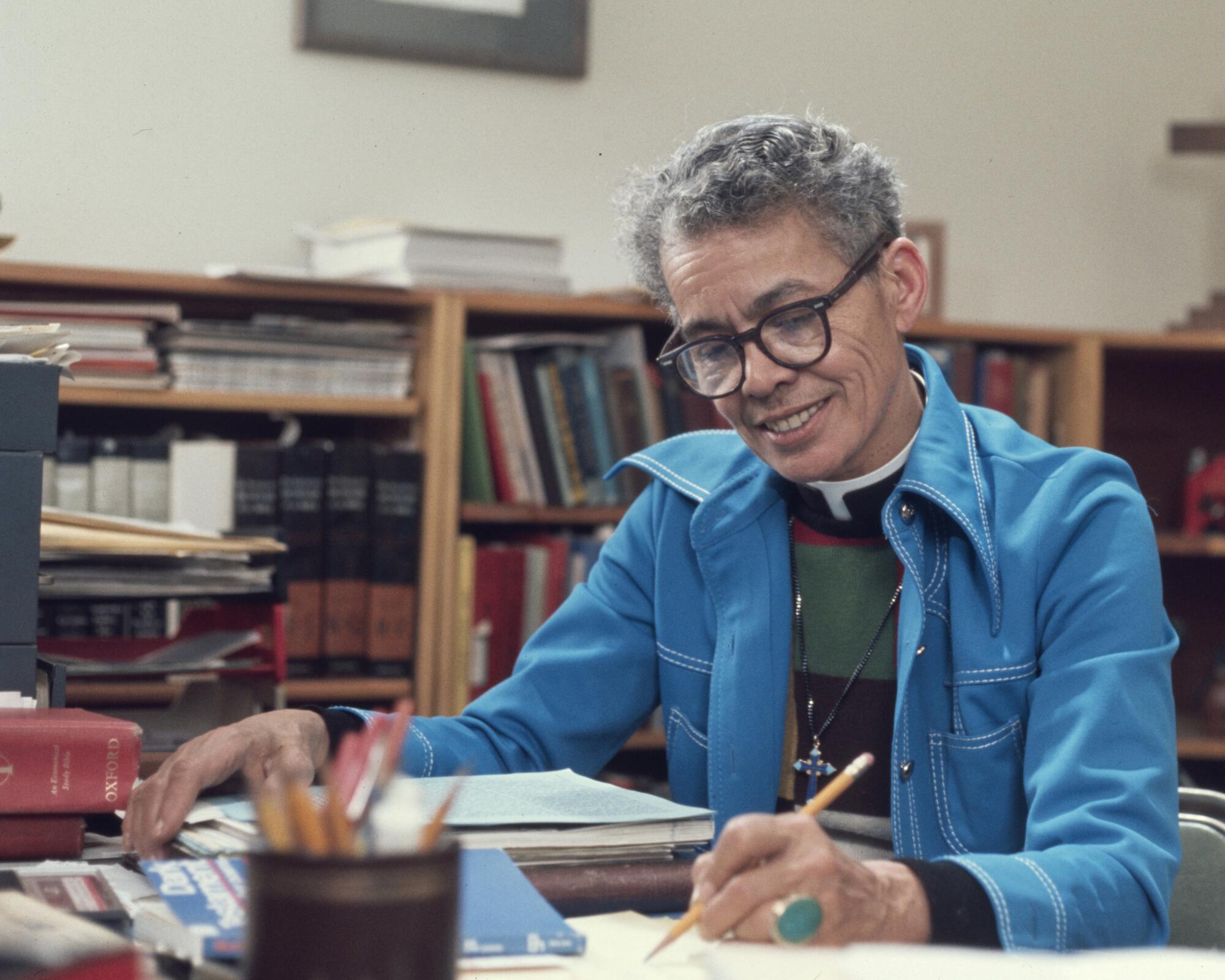

Pauli Murray in 1971 at age 60 as a law professor at Brandeis University.

But the importance of engaging with, creating and preserving archives of queer and trans people is about more than just the personal, Deleon contends. “Many years from now, people are going to look back and ask where all of this expression and talent [that’s been taken for granted] came from,” she says. “They will ask, and we need to ensure the documentation is there that upholds [those] legacies.”

“My Name Is Pauli Murray” is part of the effort to preserve and amplify Murray’s profound legacy, as is the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice in Durham, N.C. And in the process, they will unlock worlds, activate possibilities and extend lineages in the imaginations of generations who will one day, if not today, need Murray’s example to keep pushing society forward.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.