The catalog to the U.S. Film and Video Festival in January 1981 featured a single page with a photo of a group of 20 or so people leaning against a wooden rail fence. Among them was Robert Redford, dressed in jeans and a puffer vest, in front of a snow-flecked mountain range.

The copy proclaimed, “The Sundance Institute, a fledgling organization for filmmakers is proud to announce its establishment.”

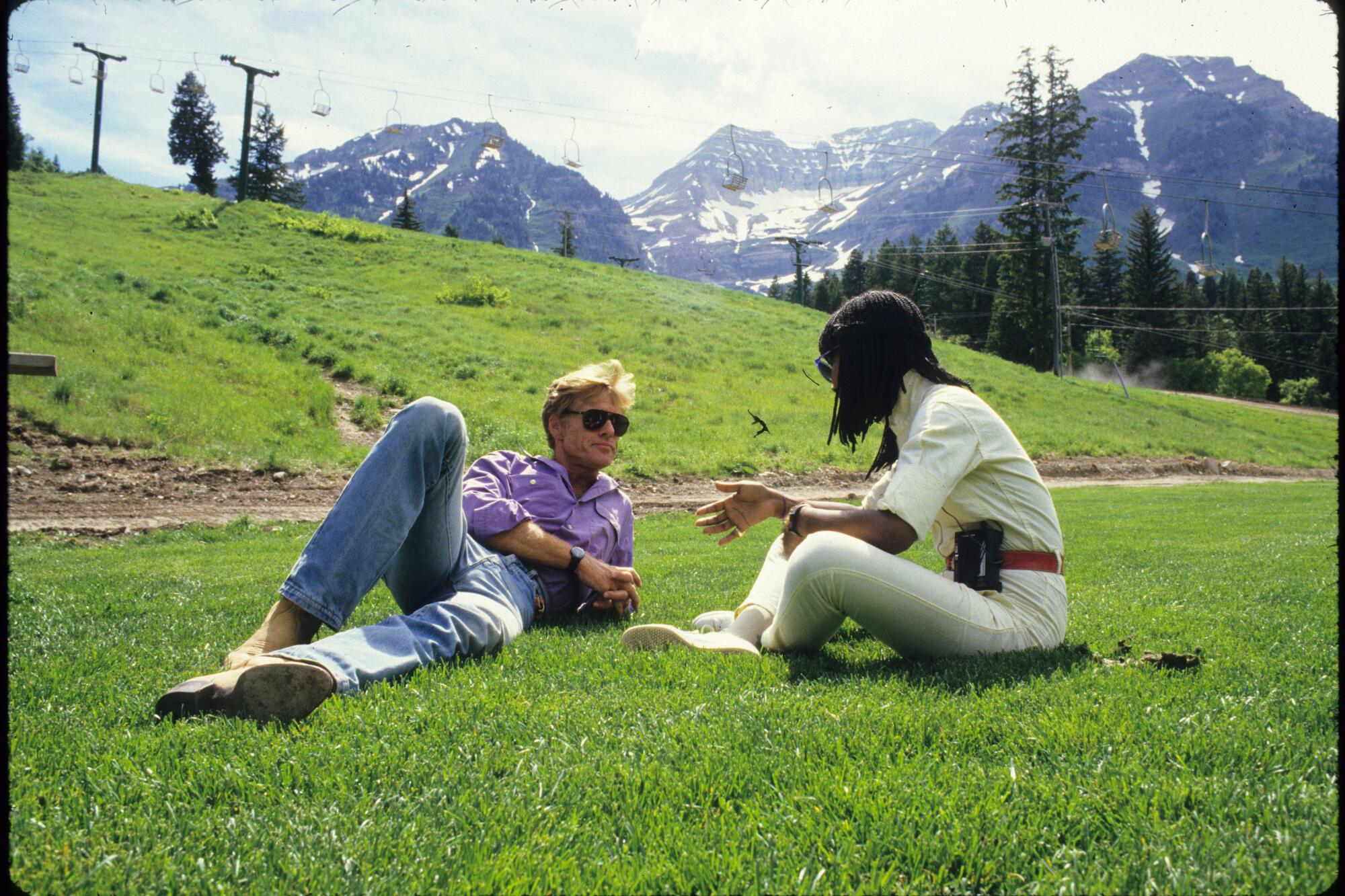

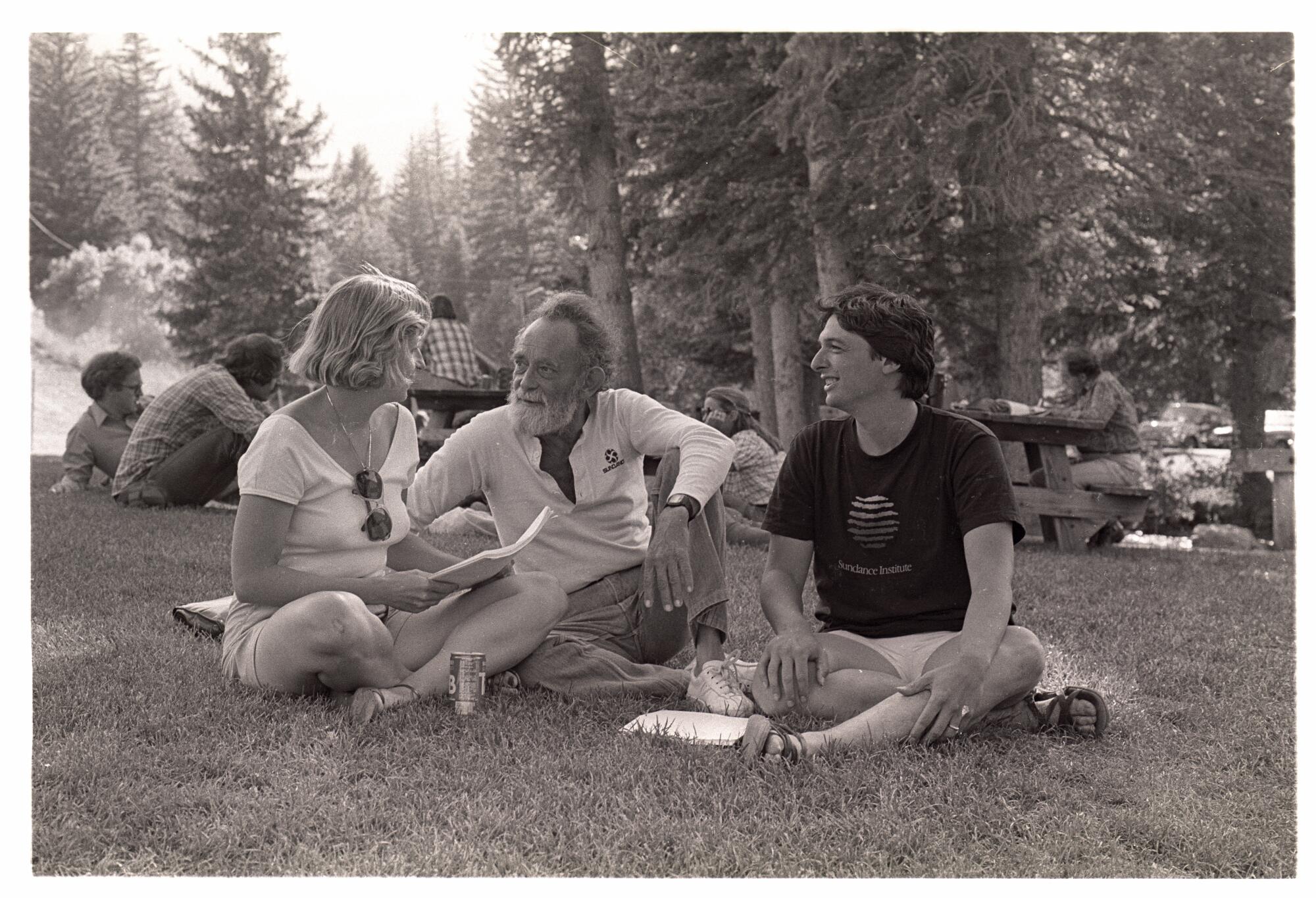

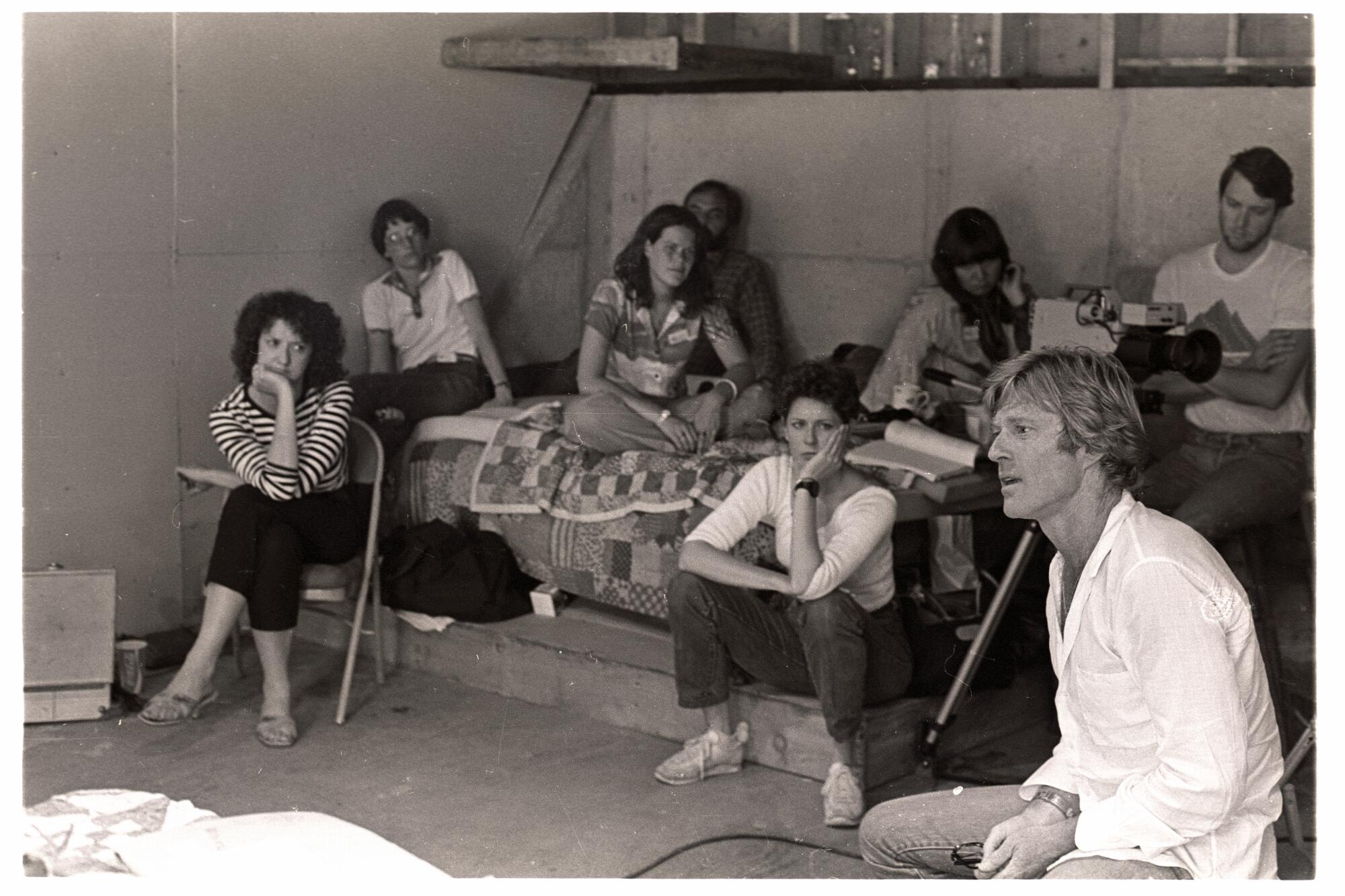

Later that summer, the institute’s lofty goal to serve “the imminent need among aspiring, professional and independent filmmakers for tested, collaborative communication” came to fruition with its first filmmakers lab that paired aspiring filmmakers with seasoned professionals for intense, intimate work sessions on a sprawling property in Utah.

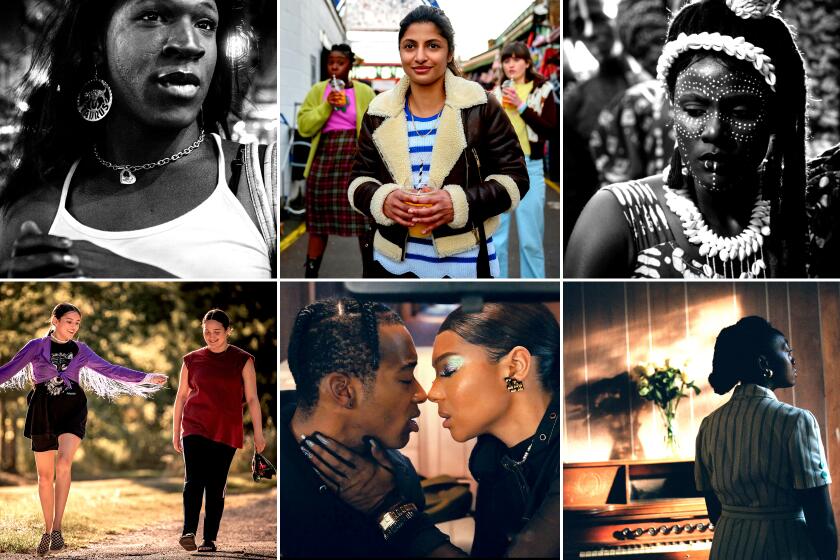

Since then the institute has grown to launch and support the careers of generations of artists, expanding with programs and events all around the globe.

Though the Sundance Film Festival may be the more public-facing and more widely known event, the labs predate the festival. Via email, Redford recalled the impulse behind the founding of the institute and launching of the labs.

“The labs will always be the core of our mission and the origin of the institute — once we started the labs and saw the inspiring work, it was clear that we needed to find ways to make sure that these films were seen, which lead to the festival. It’s a symbiotic relationship.”

And while the labs have now supported 40 years’ worth of filmmakers, including Quentin Tarantino, Euzhan Palcy, Alfonso Cuarón, Paul Thomas Anderson, Marielle Heller, Ryan Coogler and countless others, it speaks to the ongoing vitality and importance of the work to see the impact alumni continue to have at arthouses, during awards season and on more mainstream, commercial filmmaking. The directors behind numerous upcoming potential blockbusters — such as Nia DaCosta with “Candyman,” Cary Fukunaga with “No Time To Die” and Chloé Zhao with “Eternals” — are alumni of the Sundance labs. The new FX series “Reservation Dogs” was created by Sterlin Harjo and Taika Waititi, who met through their connections with Sundance’s Native Filmmakers Lab.

A group of veteran insiders of the institute itself and alumni filmmakers — some lab fellows, some advisors and some both — recently shared some of their recollections about the lab programs. While the Sundance Institute has grown to hold events all over the globe, the creative heart of the lab programs may always be somewhere on a mountain in Utah.

Robert Redford (founder and president, Sundance Institute): When I started the institute, the major studios dominated the game, which I was a part of. I wanted to focus on the word “independence” and those sidelined by the majors — supporting those sidelined by the dominant voices. To give them a voice. The intent was not to cancel or go against the studios. It wasn’t about going against the mainstream. It was about providing another avenue and more opportunity.

Michelle Satter (founding senior director, artist programs): I knew it was supporting filmmakers. I knew that Robert Redford was the visionary and at the center of it. I had seen all the films he acted in, but I’d also just seen “Ordinary People.” I mean, he was an incredible role model who was starting something for filmmakers that was going to be a creative space for artists to learn and grow. Why would you say no to that?

And I fell in love the first day with the creativity, that kind of renegade spirit of the lab, all the artists that were there and this kind of great experiment. But also the feeling of that space and the generosity of that opportunity for artists to really push their boundaries as creators. So I stayed on.

The lab is designed to help you discover who you are to help you tell the stories you feel you absolutely need to tell. Unlike movie studios ... they’re not trying to create a formula.

— Scott Frank, creative director, screenwriting lab

Gregory Nava (filmmaker; part of the first lab with “El Norte”; lab advisor): They were going to have their first lab; they were going to select these films, bring these filmmakers together and bring resources to these films that we could never hope to have. So they picked “El Norte” and me. It was the first film to go through their process.

And my God, it was life-changing. It improved the script tremendously. And one of the things I’ve got to say about it is that they not only said, “Here are things that can help you,” but they were also very open to what we wanted to do. That was different. It wasn’t imposing on you the whole Hollywood development system. It was like, “Let us help you do what you want to do.” Well, that was like the sky opening up and a light coming through, because all you heard [from the industry] was, “This is no good. You can’t do this, it’s not commercial. It won’t work.” But suddenly you had people like [advisors] Waldo Salt and Sydney Pollack telling you, “No, what you want to do is good.”

Tabitha Jackson (director, Sundance Film Festival and public programming; previously director of the documentary film program): From the outside of Sundance, one is aware of the noise and glitter and glamour and all that stuff at the beginning of each year which goes with the festival. But what I felt to be a kind of quiet soul of the work of the institute is the year-round artist support, and this very intimate expression of the labs, these individual transformations that you could witness, not easily describe, but learn from and be restored by, were just happening again and again. And that kind of unassuming quiet way across nonfiction and fiction, theater, music, emerging media, it’s just an incredible creative sandpit.

Sundance’s Tabitha Jackson won the festival director gig, then the pandemic hit. How she’s leading the film festival’s 2021 edition into the future at a pivotal time in history.

Bird Runningwater (director, Indigenous, diversity, equity and inclusion and artist programs): We challenge ourselves, in that sometimes the form of material, the level of craft, maybe something is a bit more raw, but you can just hear the voice. That’s what we’re tuned in for. I feel like our curatorial practice is just really being able to find those voices. And sometimes you stay in touch with someone long enough and you know that this is the moment, with just the smallest little bit of support, it might even just be a grant or an intensive or being accepted into the lab, and that little bit of time and attention, you can just see people pop and transcend after that. And so it’s a lot about the right time, right place, right artist, right material. It’s a lot of variables, a very complicated equation.

John Cooper (director emeritus, Sundance Film Festival; festival director 2009-2020): I worked at the lab for four years, ‘88, ‘89, ‘90, ‘91, and I still kind of did some stuff in ’92. At first just as a volunteer; I did housing. And then what was called the lab manager back then, which is kind of like foreman of the mountain, making sure everything’s running OK. It was just kind of like running a camp. It was fun. And I met such amazing people. That’s what got me hooked on Sundance for sure.

I invented the first housing chart and I think that’s where people took notice of me. Because you have these crazy cabins with rooms and you kind of memorize them all. And it’s like, “All right, you’re a crew member. You’re in the twin bed, kid’s room with the strawberry patch kid bedspread and Alan Alda, you get the big room that has a big view.” You have this house that really is like a family house of sorts. You know, it’s like dad and mom are in the big room. And then, you know, the teenage kids are over here, which are the filmmakers, and then the crew and interns and everybody that worked for me lived in the small bedroom. So it was pretty wacky.

John Cooper will move into an emeritus director role after the conclusion of this year’s festival. He shared some of his favorite memories from his years at Sundance.

Keri Putnam (CEO, Sundance Institute since 2010): Before I came to Sundance, I was a creative executive at companies developing scripts and material, working with writers and directors. So the Sundance labs had always carried a kind of a mythology. That’s where interesting talent comes from. It’s a place where people go to do work that executives never get to go. So you never quite know what happens there. It’s a mysterious place where the artists go. And I had been lucky enough to work with several filmmakers on projects that had come out of the labs or artists who had come out of the labs over the years, so I had known what the impact of the labs was through seeing the work I had been an executive on.

So I knew the creative work was excellent, but it was also a bit of a black box and there was an opportunity I felt to be able to amplify the impact of that incredible work coming through there in terms of what it meant — not just for the institute in terms of awareness, but also what it meant for the field and the artists in terms of opportunity coming out of that.

Yance Ford (filmmaker, “Strong Island,” which played at the festival; also a fellow and advisor at the labs): Sundance had this unique space that really didn’t exist anywhere else for people like me, who were just coming to filmmaking, to say, “This is where you belong as well.” And I know that the labs have done that for many, many people who are now super-famous, but they’ve also served the same purpose for me, in my work. It’s not that Sundance sort of made me feel legitimate, it’s not about a stamp of authenticity. But they created an environment where the only expectation of me was that I was growing as an artist and I was growing as a filmmaker and a director. It was a turning point for me.

Dee Rees (filmmaker; both the short film and feature film of “Pariah” played at the festival; a fellow and advisor at the labs) : The short film [of “Pariah”] hadn’t screened at Sundance — it actually got rejected the first time we submitted it. Then I did the screenwriters lab and then the short got into the festival that next year.

And then I did the director’s lab in ‘08. I had just come out of film school. And having the labs as a thing to go to was the only thing I knew for sure was gonna happen next as a filmmaker. So it came at this very vulnerable, tenuous time. I was really glad for it, because it was my first time getting to just meet other filmmakers up close in that way and also getting to kind of connect to industry in this kind of protected way. So it was a first for all of that. And so coming out of film school, I was like, OK, I have a thing to do. It was really bolstering.

Runningwater: We’ve maintained a commitment to this idea of inclusion since our founding. We’ve held steady to supporting the work and having the most diverse voices in our labs to develop and support going way back. And just now I feel like the industry is starting to catch up. We’ve been ahead of the curve for a while. And so now, [at] this racial reckoning moment, we’re being inundated and flooded with requests for artists and talent which is really refreshing to see. It hadn’t been [that way] in my 20 years.

So I think the culture [is] shifting, but I think it has to do a lot more with this racial reckoning moment that we’re in, the whole touting of BIPOC with the understanding of the “I” in BIPOC means “Indigenous.” Everyone in the industry realizes Indigenous is their blind spot. And so because we’ve been around and had this commitment for so long, all roads lead to Sundance. And now everybody’s looking for writers, everybody’s looking for directors, everybody’s looking for producers, everybody’s looking for content and stories.

Taika Waititi (filmmaker; participated in the screenwriting lab with “Boy” and the directing lab with “Eagle vs Shark,” which both played at the festival): The festival is meaningful because we had a platform where we could show our films, but with the labs, that wasn’t a thing. When you’re Indigenous or when you’re in a minority, a lot of time, you don’t want special treatment, you don’t want to be like, “Oh yeah, I’m the token Native, to come in and tell this funny, quirky, sweet little story.” There’s none of that. It’s not like you’re here because you’re a Native voice from New Zealand in the labs. It’s like, “You’re here because we like your storytelling. Tell me about your script.” And “Eagle vs Shark,” there’s nothing Native about it other than me.

But the power of the Native program, that one is very important because that is a space where Native writers and Native filmmakers and directors can come together to support each other. And it doesn’t feel like tokenism, because it’s all done by people who are Native, who understand Native voice. It doesn’t feel like it’s checking the box and OK, “Well, we got that, we got the Native American representation here because there’s that one person.” It’s everyone. So that one I like a lot too.

Rees: I never felt like a checkbox, I never felt like I was a diversity person, I felt like it was about “Pariah.” And so in that way it felt good. It felt like Michelle was genuinely interested in me and genuinely interested in “Pariah.” And so it felt organic in that way.

Ford: I think that for people who don’t have the experience or being in the minority in some spaces, it might not seem like a big deal that the fact that I’ve never been the only African American in the room, the fact that I’ve never been the only member of the LGBTQ community in the room, that somebody else has always supported stories by and about communities of color, by and about the LGBT community, in its values and its programming and that its values show through support of artists, that’s huge.

I never felt like a checkbox, I never felt like I was a diversity person.

— Dee Rees, filmmaker

Kasi Lemmons (filmmaker, “The Caveman’s Valentine” opened the 2001 festival; lab advisor): I remember being incredibly impressed from the beginning with the quality of the filmmakers, the quality of the writers and the other advisors and just being like, OK, this is rare air, this is a tremendous honor to be amongst this group of people. So I tried not to focus on my own insecurities and I tried to think about, what do I know about story? You know, what have I learned about story? And that’s what I tried to share. Like, OK, “Eve’s Bayou” was a successful story that I wrote. So did I learn anything? It was a question, but I was so delighted to be in the company of that many talented people that after I did the first lab, I had to get invited back. And it’s become a staple in my life. I didn’t know if I ever thought it through to the time that I would turn the corner and just be kind of a permanent Sundance advisor.

Sundance looks for very specific voices, very individuated voices and so the people themselves, just to hang out with a group of artists where there’s no posturing, you’re just there and you’re just talking about art and voice and storytelling with incredible people. It’s just very, very life-affirming. So in an industry that can be a little soul-sucking, let’s just call it what it is, to reinvigorate yourself continuously means a lot.

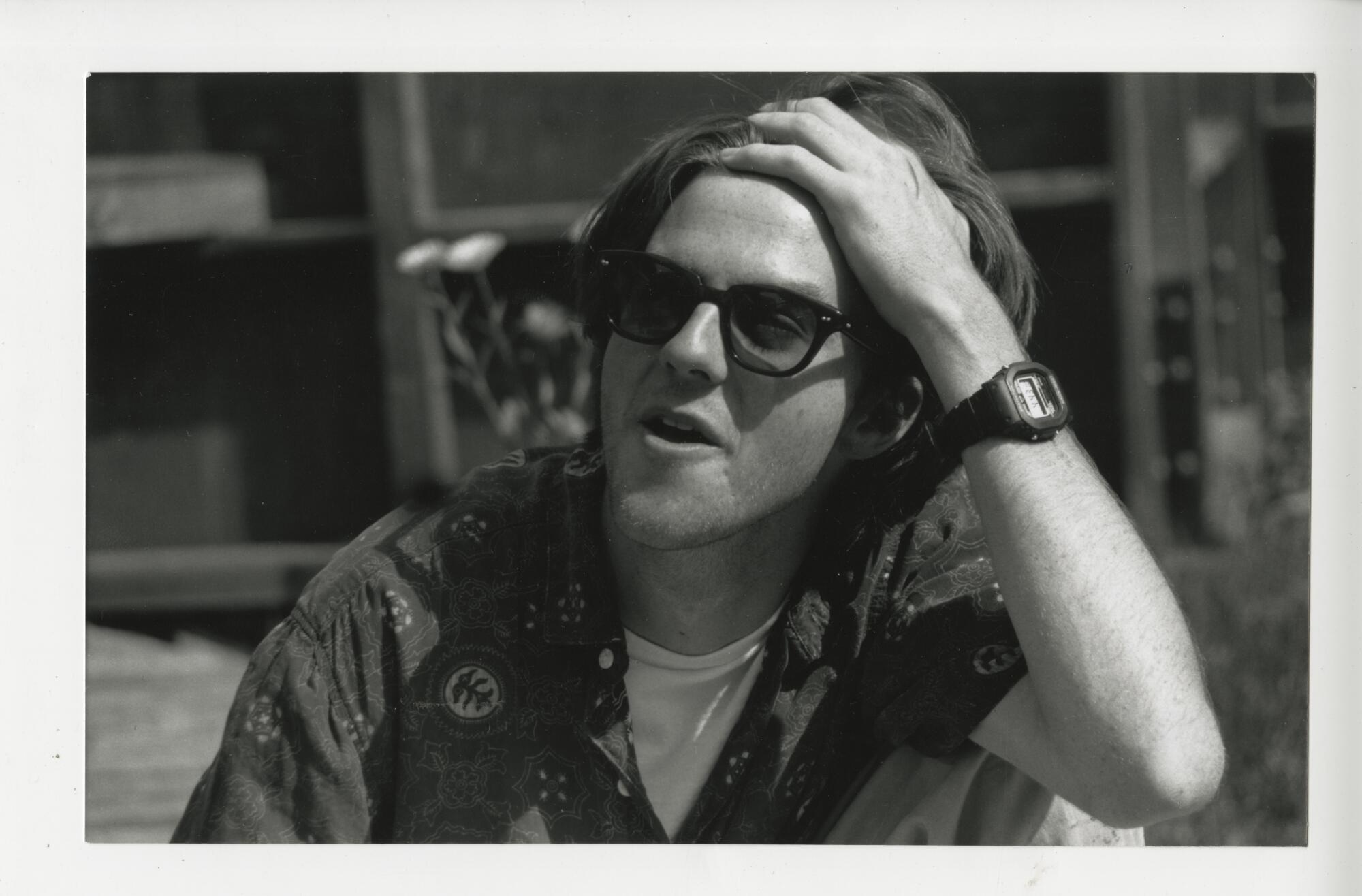

Scott Frank (creative director, screenwriting lab): If you try and learn in the industry, they don’t always let you fail. And you only learn from making mistakes. That is the best way. And Sundance encourages you to try things you might not normally try. They encourage you to go down the wrong road or to make mistakes so that you can learn and yet feel safe about it. And that’s a huge thing because that doesn’t happen in our industry. We have either film schools, which are trying to justify very expensive curriculum by creating courses that are more craft-oriented than anything else, or you have studios, which the only thing they’re teaching our young writers is how to become studio writers.

Sundance’s VR, AR and other interactive works show the power of storytelling through evolving technologies and let the fest reach a global at-home audience.

And then there’s Sundance. The process of the lab is designed to help you discover who you are to help you tell the stories you feel you absolutely need to tell. Because unlike movie studios, they don’t believe they figured anything out. What they understand is that it’s all a mess and you have to embrace the mess and it’s wrong until it’s right. And that’s really what they figured out. And they’re not trying to game anything. They’re not trying to create a formula for anything, quite the opposite. They’re starting with there is no formula. There is no way to game any of this. You can only let people try and try again and help them figure it out. And through a dialogue, through real conversation about the work, help them find their way through.

Waititi: You take and leave whatever you want. One of cool things about the writers lab is you’re encouraged not to take any notes — you just listen and whatever it is that resonates with you or you think is applicable to your work, that’s the kind of stuff that will stick with you. It’s not about writing down every single thing that someone says, which is great because I hate that. You sit back, you have conversations with people who really get your script.

And that somehow helps inspire you to continue on with it. I think that’s a cool thing that no one’s saying to you, “You have to do it like this.” “That’s an interesting way of doing it, have you thought about this?” And you might say, “I have thought about that and that’s cliché now. I’m not doing it.” And they go, “Awesome. Great.” It’s all about people and the development of their vision, and their particular style of storytelling.

Cooper: I think I learned the essence of independence and that notion of hanging true to your own story. It’s talked about all the time. This is your story, not right or wrong. That there’s many perspectives needed, from many different filmmakers from all points of view and all backgrounds. So I learned the importance of that to film and then it became independent film.

I was trying to remember, did we really call it independent film that much back then or was it just filmmaking? Independent just meant where you’re getting your money from, it wasn’t like a point of view or a spirit. And then it became that. And I think that’s something that grew with Sundance, this whole notion of a spirit that is different from just making a film for a commercial purpose or for the box office numbers and that kind of stuff. And Redford imprinted that on us all.

Satter: I don’t think anybody, I don’t even think Redford would have imagined where we are and what we’ve become 40 years later. And I think that’s a really good thing. That’s a positive, to really be able to dream and dream big and continue to try things, never rest. I don’t know that he’s said this but I felt it’s like, don’t rest on your laurels, on your successes, that’s not important. What’s important is really listening to the artists, to the field, what do they need? And the ecosystem has been constantly evolving and always asking, “How can we support artists? How can we give them a space for risk-taking and creativity?” Imagine a possibility in terms of that work going forward.

Redford: I believed in the concept, and because it was just that, a concept, I expected and hoped that it would evolve over time. And happily, it has.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.