Newsletter

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

After William Morris super-agent Ed Limato died in 2010, his onetime assistant and close friend Richard Konigsberg was entrusted with liquidating a sizable estate. First went the art and furniture, then the house. Over the years the last remaining boxes of what couldn’t be assigned monetary value made their way to the garage of Konigsberg and his partner Craig Olsen. Eventually, Olsen got around to rummaging through the cartons. That’s when the real treasure emerged.

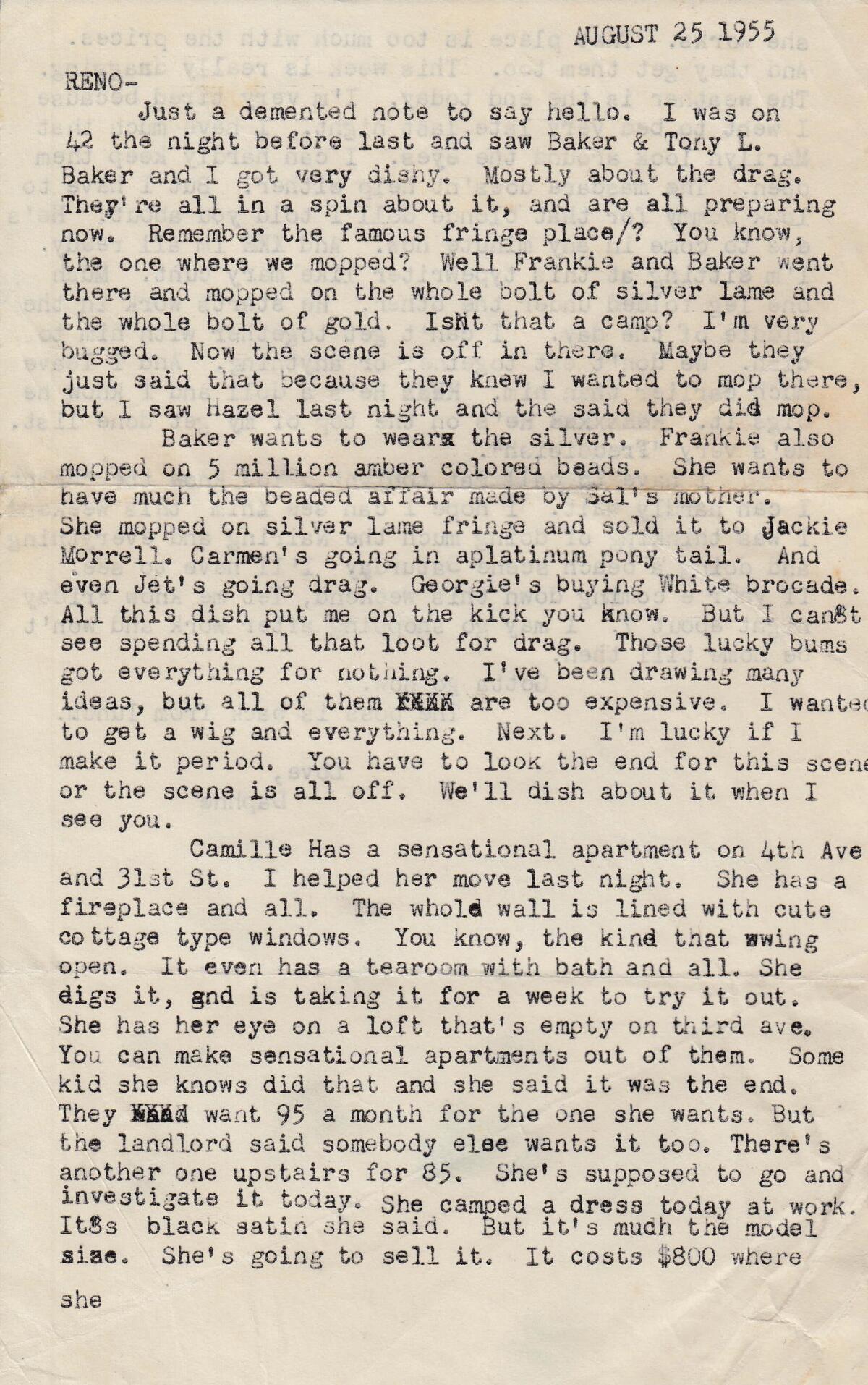

Inside the first box he opened, almost as if they wanted to be found, were roughly 200 pages of letters — some neatly typed, others beautifully handwritten on stationery or scrawled on a postcard. The missives were filled with elaborate details of stolen wigs, sequined cocktail dresses and sexual encounters, all addressed to someone named “Reno Martin” and signed with names like “Daphne” or “Josephine.” Collectively, the letters painted a vivid portrait of an intimate existence among a tight group of friends in the late 1950s and early ’60s in New York.

“At first I thought, ‘These are incredibly personal. I shouldn’t be reading these,’” Olsen says. But then he quickly grasped why there was so much focus on hair, eyeliner, the frequenting of underground nightclubs. “I realized they were drag queens,” says Olsen, who picked up the phone and called his friend, Michael Seligman, a senior producer at “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” with an urgent request: “You’ve got to get over here and see what I have.”

At first, Olsen thought the letters might become source material for a future one-person show or, perhaps, a mystery documentary called “Who Is Reno Martin?” Then Seligman got in touch with the ONE National Gay and Lesbian National Archives at USC. He explained what Olsen had found and asked if he could compare the Limato letters with anything similar in the archive’s files.

“There was a very long pause,” says Seligman, “Then the guy said, ‘You have what? I can promise you there’s nothing like what you’re describing.’”

Only then did Seligman and Olsen realize they had stumbled upon rare artifacts of LGBTQ history.

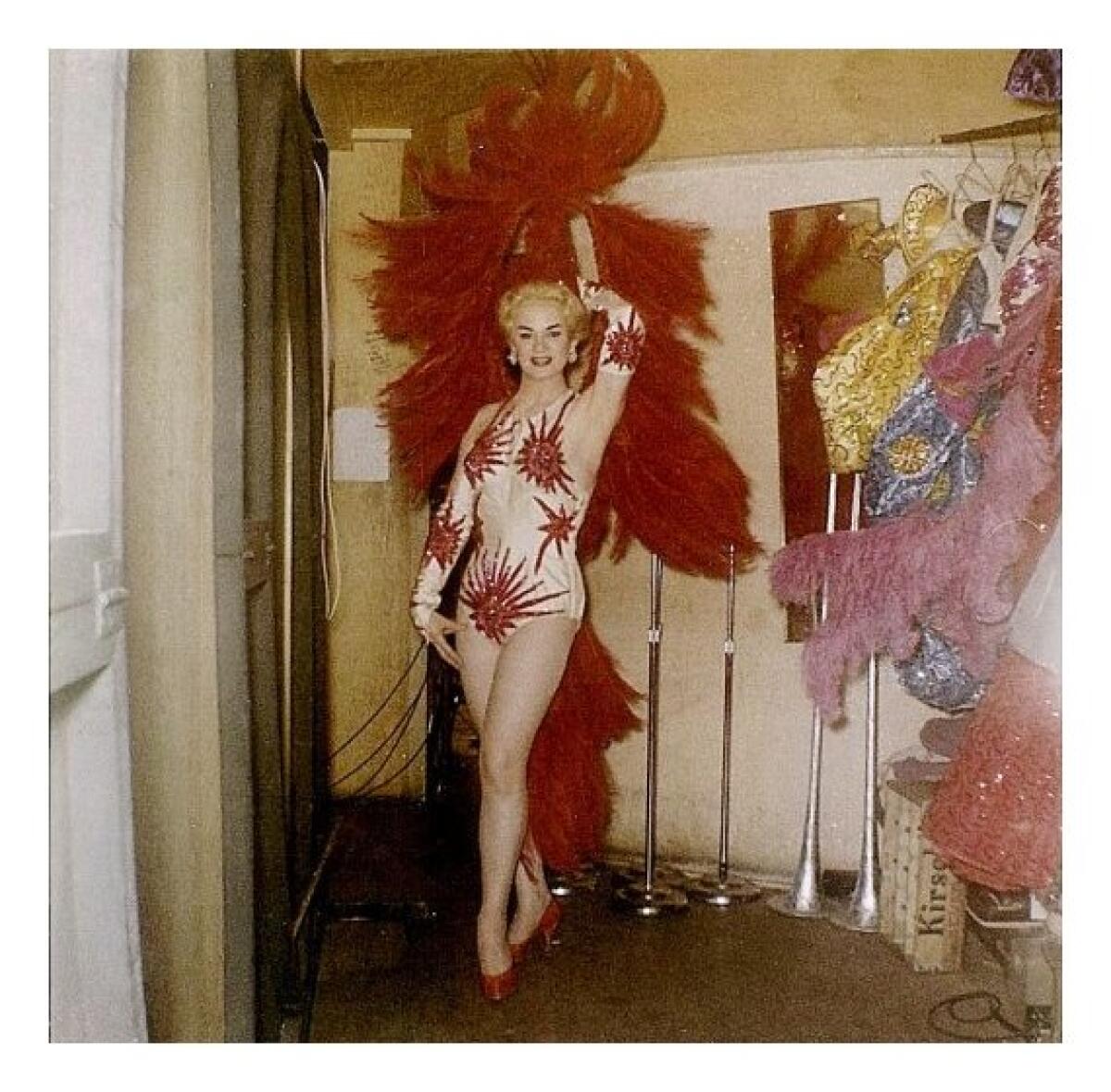

Given that Seligman once spent time as research producer at the celebrity-obsessed TV docu-series “Mysteries & Scandals,” it should come as no surprise that he’s turned the fruits of his investigation into a documentary. “P.S. Burn This Letter Please,” co-directed by Seligman and Jennifer Tiexiera, features archival imagery from 74 sources and interviews with experts who’ve studied and can contextualize the gay scene in midcentury Manhattan. But the power and charm of the film rests on the uninhibited, on-camera accounts of nine of the letter writers.

The men now in their 80s and 90s, were often ostracized by the gay community and faced significant jail time if caught in public in women’s clothing. Still, the subjects are so defiantly themselves that it’s easy to understand why the film’s tagline is: “Their greatest act of resistance was simply existing.”

“I don’t think drag queens get enough credit for being on the front lines of the whole Pride thing,” Seligman says. “They were the ones who refused to fit in. They were the ones putting their necks on the line. Night after night, taking the knocks, being rejected, being made fun of, but they were still getting up every day and still doing it.”

A woman’s mafia story: “Mob Queens” hosts Jessica Bendinger and Michael Seligman dig into the life of Anna Genovese — mob wife and drag queen club boss.

Seligman found a key piece of the letters’ puzzle when his first sit-down interview subject, Henry Arango, revealed one of Limato’s most closely held secrets. During a period the future Hollywood power broker worked as a radio deejay just outside of New Orleans, Limato went by the name Reno Martin.

This information alone didn’t guarantee a successful documentary. So Seligman, a first-time director, sought a collaborator who better understood how to build story arcs and momentum out of a stack of 60-year-old letters and raw talking-heads footage. Enter Tiexiera, a veteran documentary film editor, who agreed to watch the Arango interview. “He was just the brightest shining light I’d ever seen on camera,” Tiexiera says. “I basically remember telling [Seligman], ‘If you‘re going to make this film about these people and let them reconstruct their history from their own mouths, then I’m in.’”

Over the course of five years, working from the nickname-signed missives, “P.S. Burn This Letter Please” slowly took shape. “Often it was just taking every single bit of information, trying to form some kind of picture of who this person was, then cold calling,” says Seligman, who eventually hired a private investigator. The assignments often starting with a vague, “So we know this guy’s first name is Joe … .”

Along the way, when his “P.S.” research led him to mafia kingpin ex-wife Anna Genovese, who was the proprietor of some of the most popular ‘50s-era drag clubs in New York’s Greenwich Village, Seligman embarked on a side project, a podcast called “Mob Queens,” which he cohosts with Jessica Bendinger.

After Seligman and Tiexiera finished “P.S. Burn This Letter Please,” the global pandemic upended their plans to premiere the feature documentary at the 2020 Tribeca Film Festival. Instead, it hit the virtual film festival circuit, where comparisons to “Paris Is Burning,” Jennie Livingston’s portrait of New York’s ball culture, were often made. One review called it “an essential foray into a forgotten history of identity, rebellion, and art.”

The word about “P.S.” has continued to spread. Discovery+ began streaming the documentary in January, and on June 28 it will be available on iTunes and Amazon. Last week, the Tribeca Film Festival staged a sort of in-person do-over, a sold-out outdoor screening of “P.S.” at Hudson Yards where the filmmakers and their drag queen subjects — or female impersonators, as many prefer to call themselves — got to see “P.S.” with an audience for the first time.

One of the interviewees who couldn’t attend the event was Terry Noel, who in “P.S.” details how the drag nightclub impresario Genovese paid for Noel’s sexual reassignment surgery. When Seligman first met Noel, she was the one who actually framed the then-amorphous project for him.

“She said, ‘Oh, I get what you’re doing. You’re not telling a story — you’re telling the story,’” says Seligman. “The story being: You come from a small town. You think, ‘There is nobody here like me. I need to get out of here. I need to go to the city. I need to find my tribe.’ To Terry’s point, we’re telling the story of a lot of queer people. And I think that’s why [‘P.S.’] has resonated with so many who’ve seen the film, even if they’re not a drag queen.”

Seligman’s voice suddenly grows thick with emotion. “I still get choked up talking about this,” he says. “Finding drag gave them a community, a sense of who they were. It was the thing that saved them.”

More from Margy Rochlin

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.