Why World War I films, like ‘1917,’ have a different feel than those about WWII

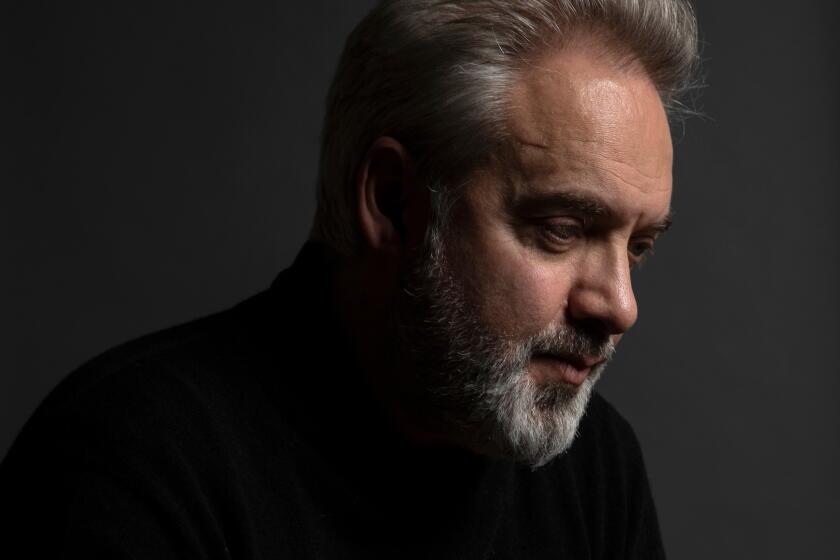

Director Sam Mendes’ new film, “1917,” tells the story of two men on a mission to save 1,600 British soldiers from being slaughtered by German forces leading them into a trap. But in its own way, it’s every World War I movie in microcosm: the trenches, the scarred battlefields, the rats, the gruesome deaths, the utter futility of a conflict fought over minuscule pieces of land; a war that seems to make no sense, despite the heroism of its combatants.

“The First World War is the beginning of modern warfare,” says Krysty Wilson-Cairns, who co-wrote the “1917” screenplay with Mendes. “It began with cavalry, horses and men in pristine, brightly colored uniforms, and it ends in tanks, aerial warfare, machine guns, chemical weapons and mud. Millions died over inches of ground.”

That seemingly pointless conflict has, nevertheless, provided filmmakers with plenty of downbeat inspiration, especially when compared with films about World War II.

World War I “allows you to tell a particular kind of war story,” says Mark Sheftall, a Bucknell University history professor who teaches courses on global warfare. “Because of the way people understand World War I, setting a movie in it tells you about the horrors of war, the futility; you can tell it as a tragedy, as disillusion. And people go, ‘Yes, war is like that.’

“Whereas World War II, that’s a story of victory, it’s the horrors and all that stuff, but typically the outcome is victory. You look for a positive resolution that can justify all that sacrifice, but you don’t have that in World War I.”

Starting with 1930’s best picture Oscar winner, “All Quiet on the Western Front,” here are some World War I movies to watch.

Wilson-Cairns has a similar view of the two conflicts. “The Second World War is a very clear battle of good versus evil. “The Nazis were despicable. In the Great War, the battle wasn’t about the destruction of evil; in fact, the real fight was survival — which is the story we wanted to tell in ‘1917.’”

This sense of despair and disillusion can be seen in any number of films about the Great War, many of which, like director Stanley Kubrick’s 1957 classic “Paths of Glory,” the 2017 British film “Journey’s End” and the aptly named 1999 British film “The Trench,” realistically depict the slaughter that took place along the Western Front.

Made primarily by Europeans about Europeans, these movies often differ markedly from films about the American experience, such as “Sergeant York” and the 1940 James Cagney feature “The Fighting 69th,” mainly because the U.S. did not enter the war until well into its fourth year, thereby avoiding some of the worst of the conflict. (The poster for “The Fighting 69th” even featured three smiling doughboy faces, something you would never see on advertising for a European film about the conflict.)

“We were in it only a year and a half, in combat for less than a year,” says Jonathan Casey of the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City. “The experience out of that was we made a difference, and we won the war for the Allies, and we didn’t have to suffer like the Europeans did. And that feeling is going to come through” in American films about the war.

Director Sam Mendes on the struggle to pull off his WWI epic, ‘1917’: from persuading Hollywood to make it to using technology to achieve a visual feat.

There is another significant difference when it comes to European versus American views of World War I. “Americans always try to tell the story of an individual,” says Sheftall, “when the real story of World War I is more about the mass. There have also been a lot of American movies about the war in the air and not a lot about the war on the ground. It’s more the heroic figure, like ‘Sergeant York.’”

In this respect, “1917” is something of an anomaly, since it is a British film whose focus is a pair of young soldiers on a dangerous mission. “I wanted to travel every step with these men — to breathe every breath with them,” Mendes has said, referring to the way he shot the film, which looks like one continuous take. “It needed to be visceral and immersive. What they are asked to do is almost impossibly difficult.”

Yet no matter whether World War I movies are about the micro or the macro, and despite the fact that the war occurred 100 years ago, the films about it speak to the contemporary world on two levels: the personal and the political.

“A lot of movies, like ‘Lawrence of Arabia,’ show how much difference the war made historically, like what happened in the Middle East, and the rise of Arab nationalism,” says Casey. “Or, in ‘Doctor Zhivago,’ the collapse of Russia and the rise of the Soviet Union. With movies like those, people can say, ‘I can better understand what’s going on now.’”

Adds Wilson-Cairns: “We can learn from World War I the colossal waste of life that war is. We can learn not to let small differences or politics divide us. And we can learn how to be better nations and better people.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.