Alfre Woodard needed just one take to nail the toughest scene in ‘Clemency’

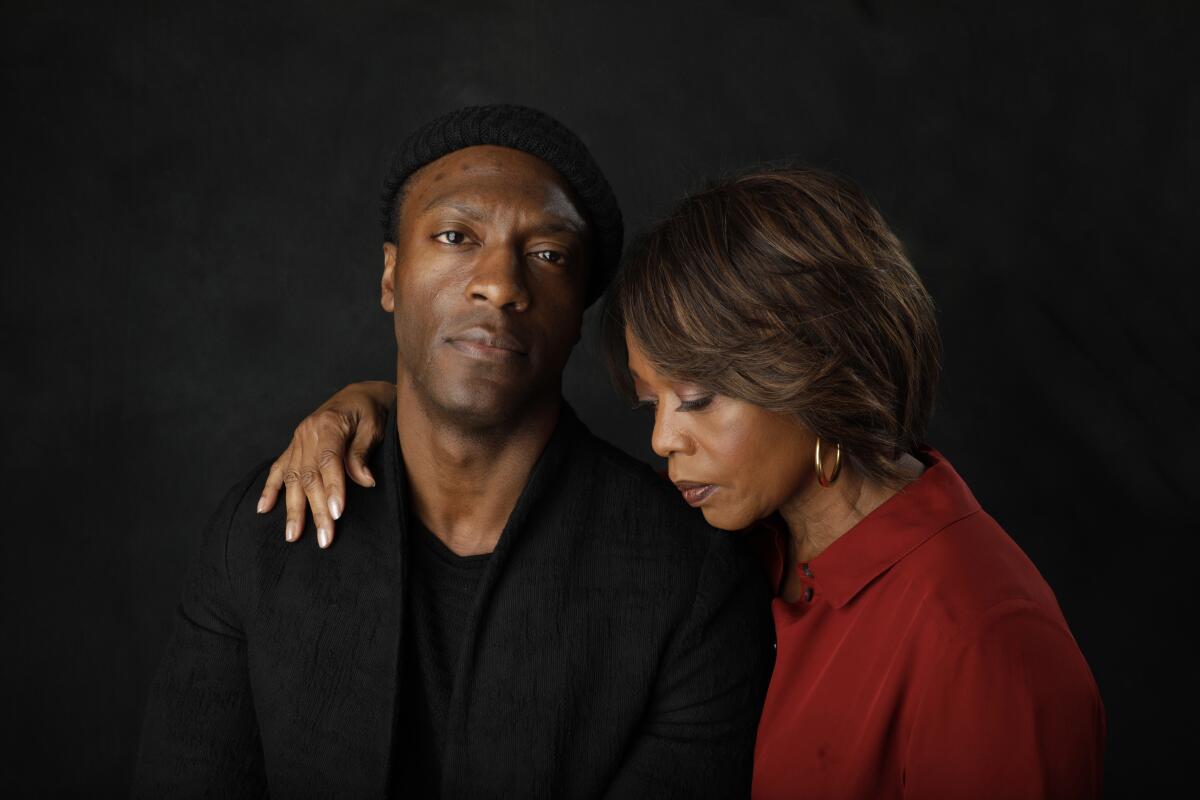

Time was of the essence on the 17-day shoot for “Clemency,” short even by indie film standards, so writer-director Chinonye Chukwu spent months prepping with actors Alfre Woodard and Aldis Hodge.

They didn’t rehearse so much as talk deeply about their characters — a prison warden in the midst of a moral crisis and one of her death row inmates, fighting for relief — so that the acting could live on its own, in the moment, once the camera rolled.

That work yielded two of the most heartrending performances of the year. Woodard and Hodge quietly bring enormous humanity to characters whose lives are irrevocably intertwined within the walls of death row, each delivering their own standout moments in scenes captured in a miraculously few number of takes.

Chinonye Chukwu’s “Clemency” is a gripping death-row drama that won the grand jury prize for American narratives at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival.

In one scene, Hodge’s condemned inmate silently crumbles while being described the menu of lethal injections that will soon kill him, the looming end to his life sinking in with shocking reality.

In another it’s Woodard’s character who strains to contain her own tormented conscience in a masterful three-and-a-half-minute take that lingers resolutely on her face, the camera refusing to let her go.

“People really came prepared,” Chukwu said at the tail end of a long journey with her second feature. (“Clemency” had its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in January, where it won the coveted grand prize for U.S. narratives and was acquired by Neon. It opened in limited release over the weekend.)

Hodge’s scene, she says, took only two takes to nail. Woodard’s stunning moment, also conveyed without dialogue and held within the immense power of her eyes and face alone, was filmed just once. “I knew as we were shooting. This is it. This is the moment,” said Chukwu.

Woodard, a former Oscar nominee, stars as Bernadine Williams, a by-the-book death-row warden who takes pride in her work. But presiding over nearly a dozen executions has taken its toll on her happiness and her marriage.

She drinks too much and doesn’t process nearly enough, and the cracks are beginning to widen. When her 12th execution, of inmate Victor Jimenez (Alex Castillo, in a brief but affecting performance), goes terribly wrong, Bernadine’s psychological fortress is further rattled ahead of her 13th: Anthony Woods (Hodge), a young African American man scheduled to die who may or may not be guilty of his crime.

“As the actor, my job always is to leave myself behind — my opinions, my history, any idiosyncrasies — and find that person, stand that person up to the point that she’s a human being,” said Woodard, joined by Hodge on a recent day in Los Angeles. “Every character I ever played, I had to learn to think the way they think. And this one took me to the other side, the absolute other side of the circle than I’d always inhabited.”

As the actor, my job always is to leave myself behind — my opinions, my history, any idiosyncrasies... and stand that person up to the point that she’s a human being.

— ‘Clemency’ star Alfre Woodard

State-sanctioned execution and the spiritual toll it exacts on those involved are explored in “Clemency,” which made history when Chukwu became the first black female director to win the Sundance Grand Jury Prize. It was a culmination, of sorts, for an eight-year journey that was inspired by the 2011 execution of Troy Davis, convicted of murdering a police officer.

Like many who followed the Davis case, Chukwu had seen the protests against his sentence, the media coverage, his claims of innocence until his death. She wondered about those tasked with carrying out his fate. “I was obsessed with the question of — ‘What must it be like for your livelihood to be tied to the taking of human life?’ Especially after there were a handful of wardens who were part of the group who were protesting against his execution,” she said.

In 2013, after making her directorial debut with “Alaskaland,” she decided to begin research on “Clemency.” She met with prison wardens, many of them women, and worked within Ohio prisons as a volunteer and teacher. Eventually those same prisons would allow her access to bring Woodard to meet with female wardens and men on death row. They sought to understand what life is like in a place built for those whom the legal system has ordered to die.

Some were forthcoming, others not; some confided the compartmentalization their work required, and what it takes to do it. Chukwu gave her characters added dimension through their relationships to others on the periphery: Bernadine wrangles a fractured home life with her husband (Wendell Pierce), and Anthony slowly begins to trust his lawyer (Richard Schiff), the only person in his world who offers a semblance of hope.

“There were some high-ranking corrections staff that got very choked up talking about the night of an execution,” Chukwu said. “I remember one person, who is part of the [execution] process, saying that she has a long drive home after every execution, and she’s so thankful for that drive because during that drive is when she just incrementally pushes it inside; by the time she gets home, she doesn’t talk about it. That was fascinating to me.”

Two years before filming “Clemency,” Chukwu sent Woodard the script. She described her vision for the film, which plays out in meticulous pacing and austere design, allowing emotion to spill out in discrete, cathartic bursts. “Only a few people could play this role, because it’s such a delicate, precise, subtle performance,” Chukwu said. “[Woodard] is one of the few people I think who could tell an entire story with just her eyes.”

It was a topic not far from Woodard’s mind. The actress, a longtime activist in political and social justice issues, thought of her childhood in Tulsa, Okla., and her own personal awakening to the realities of capital punishment.

“I grew up in a state, Oklahoma, that continues to put people to death by law,” she said. “I remember going to Sunday school and to Mass, being raised in ethics growing up. Suddenly out of nowhere they’d say, ‘So and so is being put to death,’ and I would feel sick — personally sick. ... It was, ‘He’s going to die. We’re going to do it.’ I didn’t know where to put that.

“We’re empaths, as actors and storytellers and artists,” she said. “By the time I was in my early teens, I was aware; ‘Well, why is this happening?’ And then you learn by the time you’re 17, ‘Oh — tax dollars. Damn. I’m somehow responsible.’ If you’re a thinking person and a person of heart, that’s when you start to make those steps in whatever capacity you can to try to say at least, ‘I’m standing against this.’”

“The question I kept asking with this script in particular was, ‘Do we as a society have the right to take the lives of those who have taken life?’”

— “Clemency” star Aldis Hodge

Hodge, 33, had broken through in film with 2015’s “Straight Outta Compton,” in which he played N.W.A member MC Ren. He’d landed supporting roles in the sequel “Jack Reacher: Never Go Back” and best picture-nominated “Hidden Figures” and starred in the lead role in this year’s fact-based drama “Brian Banks,” about an NFL hopeful freed from prison after an overturned rape conviction.

But it was the actor’s work on WGN’s antebellum-set drama series “Underground” that caught Chukwu’s attention, prompting her to offer him the role of Anthony Woods.

“I needed someone who could hold a scene without saying a word. I needed someone who could hold a scene with his eyes, similar to Bernadine,” she said. “I saw an episode of ‘Underground’ where he didn’t speak for like 10 minutes and he had to plan an escape without speaking. He was magnetic. I said, ‘Oh — this is Anthony. Done.’”

For Hodge, who filmed his scenes in just five days on location in a former Los Angeles prison, “Clemency” presented an opportunity to merge his personal activism with his acting work, and to reflect on his own ideals.

“It inspired me to look at the way I look at empathy and really have a conversation with myself about judgment: ‘Do I judge too harshly? Am I too quick to judge? Do I have a right to judge?‘” he said. “And the question I kept asking with this script in particular was, ‘Do we as a society have the right to take the lives of those who have taken life?’”

‘Clemency’ director Chinonye Chukwu and ‘Just Mercy’ director Destin Daniel Cretton want audiences watching their films to rethink capital punishment.

That question chips away at Bernadine at the helm of an operation that by necessity runs on procedure and routine. Administering preparations for the withdrawn Anthony as his lawyer fights for an eleventh-hour pardon, Bernadine arrives at his cell and soberly recites the day-of protocols that will end his life.

In the script, however, the drugs were not specifically named. Woodard suggested that instead of euphemistic language, Bernadine tell Anthony exactly the poisons that would be injected into his body, creating starker truths for the actors to mine.

“I knew that it would trigger me and trigger you as the actor, to hear that,” Woodard said, turning to Hodge. “Saying it is so specific; it’s like, ‘I’m going to tell you everything.’ And because they have a name, it feels like this is final. The very, very basis of acting is listening and responding, because that’s what we do in life. When you’re acting you’re re-creating a human situation.

“You don’t work on it at home and get in the mirror, the way all these people try to act now — even the ones that are celebrated and practice how they’re going to look while they’re saying it! And you can’t already know how you want to act and expect how they’re going to act until you get there. For Bernadine to be saying to Anthony what’s going to happen — and what Anthony’s giving back is, ‘I’m taking a trip right now. I am not even here’ — that pressures her. That’s what was hard.”

“My experience of that scene is that I’ve never had anyone tell me how I’m going to die before, and at this point I don’t think Anthony has, either, even though he’s been on death row for a number of years,” Hodge said of Anthony’s reaction, which sees him retreat emotionally even further, his back pressed against the wall of his prison cell.

It was one of the most difficult scenes for both actors to get through. Chukwu remembered the moment vividly. “I asked after that take, ‘Where the hell did you mentally go?’” she said. “He said, ‘I was thinking about all the things I would miss out on — me, Aldis Hodge — if someone were to take my life today. My hopes and my dreams, the children I would want to have, all of it.’”

Like Woodard, Hodge prepared for his role by talking to people who live the experience. He visited San Quentin, where he spent time with corrections staff and inmates and was allowed to observe those on death row, before California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a moratorium on capital punishment in the state in March.

“With prisoners, it’s more or less, what are their hopes and dreams? Because that’s really what they spoke about,” he said. “You’re sitting there talking to men, to human beings, who are far stretched from who they were when they first got there. ... With this film I hope that people learn to see the humanity in those that they otherwise don’t recognize, to see the human before the act.”

While its makers seem to have clear positions on the death penalty, “Clemency” offers no easy answers. Those involved hope it invites the public into the complex debate. That’s one reason why identity in the film is particularly interesting, says Woodard, pointing out that though race, age and gender are present they’re not the central issue.

“Chinonye smartly says she made Bernadine an African American woman because, ‘I see myself in my filmmaking — why not make her that?’” said Woodard, adding that many of the wardens Chukwu based her research around are women of color. “But I think it serves the film really well because we stay on the point of the morality and the ethics of this situation, to take the conversation forward, because everyone is of color.”

“We usually think of a woman as the nurturer and the protector of human life, so it gets us down to — ‘There’s no distractions, Americans! You don’t get to play any card there,’” she added.

With 2020 around the corner, can “Clemency” encourage moviegoers to take more of an active role in the social and political decisions that impact them, including and beyond the death penalty?

“This is it, and you are you, whatever color or gender, you are watching this,” Woodard said. “Where are you going to put your weight?”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.