Film roles for women have seen old tropes fall away and full-fledged human beings emerge

These are interesting times to play a woman in a Hollywood movie. On the one hand, the numbers still aren’t great: The Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film study “It’s a Man’s (Celluloid) World” noted that in 2018 females comprised 35% of all speaking characters — up just one percentage point from 2017.

On the other hand, the last two lead actress Oscar winners were for very nontraditional portrayals: Olivia Colman in “The Favourite” and Frances McDormand in “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri.” Comme ci comme ça?

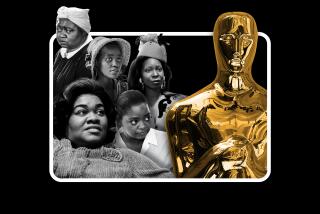

Now, take a closer look at this year’s offerings. Yes, there may still be room for a greater quantity of female roles, but what’s clear this awards season is that the quality of them has skyrocketed. Consider: a historic hero (“Harriet”), a prison warden (“Clemency”), an astronaut (“Lucy in the Sky”), journalists facing off with their creepy boss (“Bombshell”), an actress turned civil rights crusader (“Seberg”) and even a few more traditional, but nuanced, women (“The Farewell,” “Gloria Bell,” “Laundromat,” “Little Women”) are all vying for berths at ceremonies next year.

That’s a welcome change, however you slice it.

“My frustration has been that we haven’t let women play the full gamut of characters,” says “Bombshell” writer-producer Charles Randolph. “We’re in a moment now where a woman going through an intense internal conflict that is not necessarily ennobling or touching traditional maternal touchstones is happening.”

“So many stories are told of ‘great men’ and their downfalls; so rarely do you get to see that story for women,” adds Brian C. Brown, co-screenwriter and producer of “Lucy” with Elliott DiGuiseppi. “It was important for us to have a female protagonist with the complexity and flaws we so often see in male protagonists.”

Women do play the complex, troubled or irredeemable from time to time. But female roles are often defined by gender first and character second, so much so that the clichés used to portray them sometimes have nicknames: Dead Wife, Manic Pixie Dream Girl.

“For so long, women have been appendages to men who do things,” says Amy Pascal, a producer on “Little Women.” “What matters to me is what happens when there are consequences to what women say and do. If there are consequences to your actions as a human being, then you matter — good or bad.”

Lack of nuanced representation can be doubly alienating for nonwhite female characters. “Clemency” writer-director Chinonye Chukwu says her film is “a narrative, emotional arc for a protagonist who’s a black woman not defined by her race and gender. She has an entire internal world that is not about race or gender. Those things inform her living but she doesn’t go into some monologue about being a black woman. That, to me, is so human.”

It took 10 years for Chukwu to get “Clemency” made, while writer-director Kasi Lemmons says her producers on “Harriet” were trying to get that film made for seven years. “To have a black woman protagonist in a historical adventure movie is incredible,” Lemmons says. “We’re now in a place where this kind of movie is seen as viable and essential.”

“The world is 50% women; the world is diverse and there are so many stories of women to tell,” says “Farewell” producer Daniele Tate Melia. She notes that her film is absent so many tropes of what is “expected” with a female lead — for example, there’s no romance. “Nothing in the story is from the lens of a male protagonist,” she adds. “It’s all about filial love for her grandmother.”

One thing that’s been holding back great roles for women may have been belief in now-discredited box office myths: namely that women, and black women in particular, don’t sell well overseas. “Box office has proven us wrong,” says Lemmons. “I always thought it was an excuse.”

“Men got more chances to be bigger stars,” says Pascal. “More men in the past have gotten shots for the parts that made them iconic to the world. And as women get those parts, that simply will not be true.”

Simultaneously, TV opened things up. “You’re entering a world where we have so many different platforms for content that there’s more room for slightly more unusual fare, and audiences are demanding more stories,” says “Seberg” producer Kate Garwood.

Randolph agrees. “TV has burned through all the easy low-hanging fruit for women’s roles, and it’s forcing writers and auteurs to think through what the real roles are out there.”

Not every role is meant to be a breakthrough, though. “Judy” shows Judy Garland struggling with identity, body image and drugs — but her most persistent problem is that the great singer can’t mother her children. Director Rupert Goold argues that this is not an issue.

“We have to be careful as storytellers that we don’t make strong, independent, forceful characterizations a new orthodoxy,” he says. “Life isn’t like that. It would be wrong to create empowerment all the time.”

Sebastián Lelio, “Gloria Bell” director and co-screenwriter (with Alice Johnson Boher), agrees; his lead is an ordinary woman letting herself learn to live. “One thing that appealed to me in the first place is making a film about a woman that says, ‘You deserve a film.’ It’s celebratory,” he says.

And in the long run, what we see onscreen has a way of seeping into the culture at large. “We’ve been drip-fed images of masculinity and femininity that reflect the culture of the time, but they also reflect back the culture of the time,” says Joe Shrapnel, “Seberg” co-writer (with Anna Waterhouse). “It feels like there’s been a turning point in the last year.”

“What’s happening in this moment is great,” says Scott Z. Burns, writer of “The Laundromat” and director of “The Report.” “We’re dimensionalizing women, and there are so many female writers helping with this — Margaret Atwood, Phoebe Waller-Bridge. They are fully-fledged, confident women being put on the page … and that’s the best news ever.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.