Linda Ronstadt on the sound of her life

SAN FRANCISCO — Linda Ronstadt did not want a movie to be made about her life. She expressed that very clearly to any filmmaker who approached her, seeking permission to spotlight her music career.

“I’m bored to delirium talking about the past,” she replied to one such email inquiry in 2015. “Surely, you can find more worthy subjects.”

The singer, now 73, frequently insists that she didn’t know how to sing for the first decade of her career — a period during which she released the hit singles “You’re No Good,” “Blue Bayou” and “Heat Wave.” All she hears in those songs is a young woman who “did everything wrong,” belting her way up the scale instead of switching into her head voice past B flat.

“I sounded like a goat,” she says.

So a documentary about her life, no doubt filled with concert footage of her 1970s bleating? Pass.

But Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman were persistent. After her initial rejection letter (see above) she eventually agreed to have lunch with the directors. She thought their emails had been especially literate, and she was a fan of Epstein’s “The Times of Harvey Milk,” which won the feature documentary Oscar in 1985.

Over lunch, she acquiesced. But there were stipulations. She did not want to participate in a sit-down interview. (“The self-consciousness of it! Me, me me,” she groans.) And she did not want the film to focus on her progressive supranuclear palsy, a variant of Parkinson’s disease that has robbed her of her singing voice since its diagnosis in 2013.

“I think she didn’t want it to be ‘Let’s feel sorry for Linda’ and make a movie about a poor creature,” says James Keach, who produced “Linda Ronstadt: The Sound of My Voice,” which opens nationwide next weekend and will play on CNN in early 2020. “She doesn’t want to dwell on it. She says, ‘You know, I’m 73 years old. This is gravy.’”

Though she revealed her illness to the public five years ago — shortly after she sang her last concert in 2009 — Ronstadt does not like the idea of being a “Parkinson’s person.” She jokes that she has to talk about her condition with those they meet, lest they think she’s drunk when she walks.

“There’s nothing I can do about it. It’s going to get worse every day. That’s the way it is,” she says. “I feel frustrated with it. It’s hard to brush my teeth now and lift up jars, and I drop things all the time. Sometimes I fall down. But that’s the new normal. I just have to accept it. I had a long turn at the trough.”

Ronstadt is mostly housebound, spending her days inside the Sea Cliff home she bought 10 years ago. Her 27-year-old son, Carlos, works at Apple and lives on the third floor.

She likes the cottage, which is so close to the ocean that she can hear the waves at night. She moved to the Bay Area in 2005 after decades in Southern California, bouncing among Laurel Canyon, Malibu and Brentwood. She had grown tired of the “L.A. conversation,” like talking about where she bought her shoes, and wanted to be able to see the San Francisco ballet and symphony orchestra regularly.

She can no longer go to those performances because she cannot sit upright in a theater seat. Instead, she spends most of her time on a cushy white chaise, reading or talking to her friends on the phone. From this vantage, she can enjoy the view of her garden, where her cat, Tucker, roams among the hydrangea bushes.

In her living room, she is also surrounded by a wall of bookshelves piled high with stacks of diverse reads: “War and Peace,” biographies of Neil Young and Dolly Parton, a Deepak Chopra self-help guide on DNA, rows of the Encyclopedia Britannica. An original drawing from 1937’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” rests on the fireplace mantel. Her knickknacks are confined to a small tin at the center of her coffee table that houses some eye drops, a flashlight, a bottle of Advil and an amethyst crystal.

There is a piano in the room, but otherwise no evidence of her musical life. She keeps the National Medal of Arts she received in 2016 from President Obama under her bed. And her 10 Grammys? Gone. She has no idea where they are. For a long time, her manager kept the trophies in his office, and then she moved them to a storage unit. Somewhere along the way, they vanished.

“Even if I had the space, I wouldn’t give it to the Grammys. I’d hang a nice painting,” she says. “I’m happy that I got them. But it’s just a thing.”

Friedman, one of the film’s directors, admits he was initially taken aback by Ronstadt’s aversion to attention.

“It’s surprising in many ways that a performer of her stature, who had such success, remained completely unspoiled by it,” he says. “I think it’s hard to understand today, when there’s so much emphasis on celebrity and it’s all about followers and friends and influencers.”

After he and Epstein screened the documentary for Ronstadt, she told them they’d done a “good job” and said she had “no notes.” But in the privacy of her home, she describes watching the documentary as “excruciating.” Noticing how anxious she looked in front of early crowds, she says she kept thinking to herself: “Give that girl a Valium. She’s a nervous wreck.”

She even finds it difficult to appreciate her fashion sense, which has since been copycatted by many a Free People-loving millennial.

“I was just a geek standing around in Levi shorts trying to get as close to the music as I could,” she says with a shrug. “There was plenty of pressure to look sexy, but there wasn’t pressure to be dressed and styled. I never wore makeup until I was about 25. I wore a little bit of eyeliner and some mascara. But face makeup and blush and shading and everything like that? I didn’t know how to do any of that. I didn’t own any of that stuff.”

She says modeled her style off of the waitresses at the Sunset Strip club the Troubadour, particularly that iconic Betsey Johnson minidress that she wore to all her big performances. She kept the purple striped dress in her purse, washing it in the sink at night until it became so short that she gave it away to Goodwill.

But even now she maintains a bit of an edge. Although there are no more flowers pushed behind her ears, she has dyed her hair a barely noticeable shade of purple. She pushes some of her wispy bangs out of her eyes and tries to explain why she found watching the film so uncomfortable.

“It’s like your whole musical life goes by in a flash. It’s very disorienting,” she says. “I’m relieved that it isn’t something that made me look stupid. I do a good enough job of that myself.”

The movie is filled with glowing testimonials from her friends and collaborators, including Dolly Parton, Cameron Crowe, Bonnie Raitt and Peter Asher. She was most surprised that Ry Cooder — who is “like a God to all of us musicians” — agreed to be a talking head in the film because “he’s such a curmudgeon, bless his heart.”

Keach, who also produced this year’s “David Crosby: Remember My Name,” acknowledges it was far easier to find people willing to sing Ronstadt’s praises than Crosby’s.

“Doing the Crosby doc, a lot of his contemporaries felt like the experience he put them through was very rough on their relationships, so ultimately those folks didn’t really want to talk about how they felt,” Keach says. “Whereas with Linda, anyone you wanted to remotely interview was, like, ‘Sign me up!’”

That Ronstadt has maintained such goodwill in the music industry likely also has to do with the fact that she explored so many genres. Though she’s largely recognized as a pioneering female rock ’n’ roll star — she was often referred to as the highest-paid woman in rock, reportedly making $12 million in 1978 alone — she also found success as a Latin, country and opera singer.

Growing up in Tucson, she listened to a range of music: Her mother would sing Gilbert and Sullivan on the piano; her Mexican father played the music of his ancestors; her grandmother loved opera; and her sister was obsessed with Hank Williams. As a schoolgirl, she spent her days dreaming of rushing home and playing the records she’d stacked in order of preference.

“I never tried to do anything I hadn’t heard by the age of 10. I wouldn’t be able to do it authentically,” she says of her career choices. “It’s not a great idea, really, if you establish yourself singing one way and people like it and then you say I’m not going to sing anything like that now — not even in the same language. But it was interesting to me. The cliché about me is: She reinvented myself. I didn’t invent myself to start with. My parents invented me.”

Ronstadt’s childhood was formative, particularly because the Arizona community she was raised in was so close to the U.S.-Mexico border. Back then, she says, driving between the two countries was “as easy as driving to the [San Fernando] Valley — except it was easier, because there wasn’t so much traffic.”

“People came over all the time — we went to baptisms and birthday parties,” she recalls. “They were all customers of my dad, who had a big hardware business that sold pumps and farm equipment to the ranchers and farmers down there. It wasn’t hard to get across the border at all. It’s an outrage, what’s happening now. The Sonoran Desert, where I was born, goes on both sides of the border and there’s this damn fence through it now. But it doesn’t change the culture at all.”

Ronstadt — who has a red Trump-style hat that reads “Make America Mexico Again” in her entryway — feels a strong tie to her Mexican roots. She is a longtime supporter of a cultural arts program that teaches young people about traditional Mexican music and dance, and traveled to Mexico in March with Jackson Browne to support the group.

Rosa Armida Contreras and Rafael Vindiola stood to the side of a portable wood dance surface plopped down in the town square, the two high school students shyly eyeing each other after being invited to join members of a visiting music and dance group that had traveled nearly 1,100 miles south from the San Francisco Bay Area.

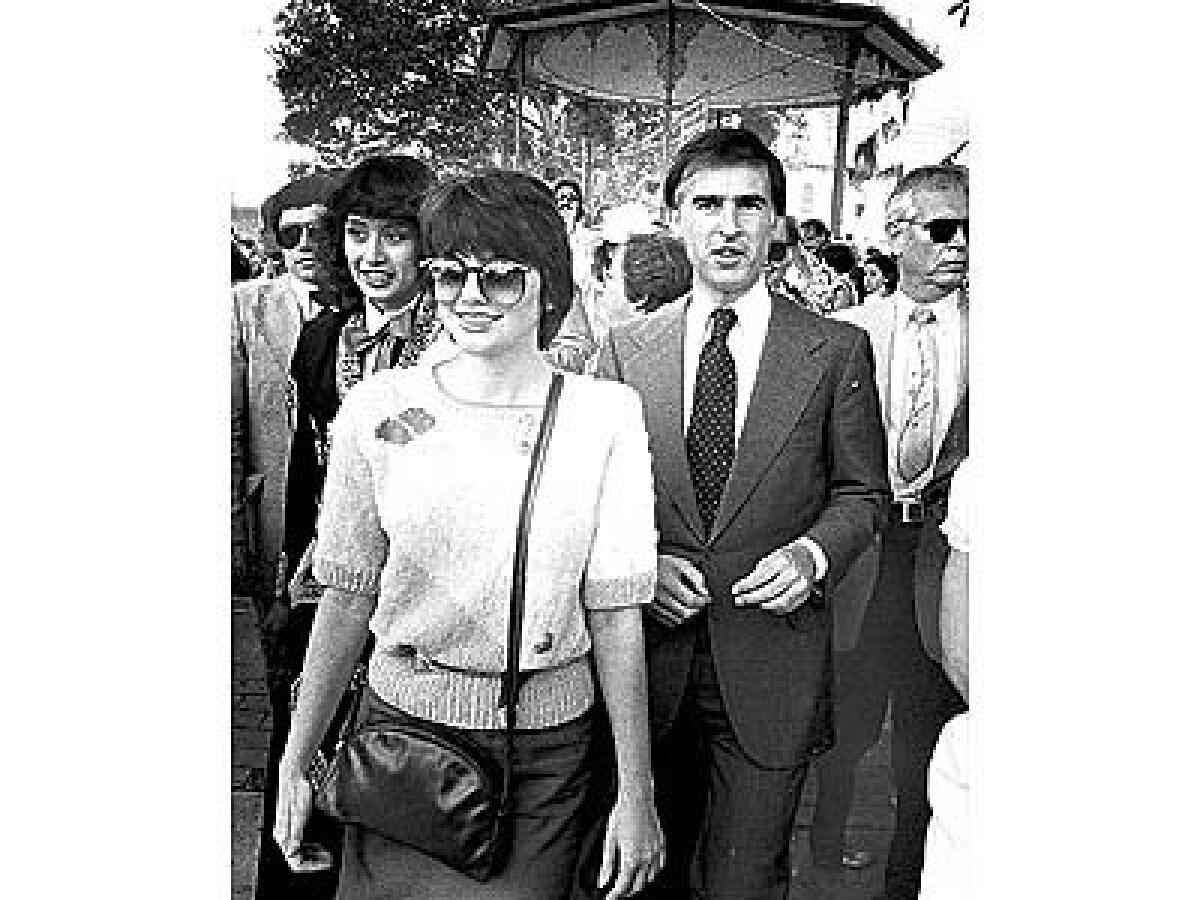

The singer, who famously dated former California Gov. Jerry Brown for years, has always been outspoken about her political beliefs. Her early views were shaped by the musicians she was fans of — Joan Baez and Peter, Paul and Mary, who she watched sing on TV during the civil rights march. When she became a celebrity, she used her platform to speak out against issues like nuclear power plants.

“I figured if people were that unenlightened, they didn’t need to buy the record,” she says when asked if she worried that her opinions might affect her popularity. “But we weren’t as polarized then. It was straights against hippies. I think it’s important for [musicians] to speak up. I don’t think anybody should, but I’m very happy when they do. I’m glad Taylor Swift is speaking up. I understand [why she was initially hesitant to]. When I’m watching somebody’s music and I really like it, and they start talking about Trump — it would spoil their music for me. I think we have a duty to protect that sacred thing. But this is too desperate.”

She gets her news from PBS and the BBC and subscribes to the Wall Street Journal and New York Times. She relies on the New Yorker for new music recommendations, and if a review intrigues her, she’ll look up the artist on YouTube.

“That’s my total involvement with mainstream music,” she says with a laugh. “I listen to a lot of opera on YouTube, recently this Czech soprano named Edita Adlerová. ... I like most of the mainstream female vocalists. I like Sia. They’re all good — Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, Katy Perry, they have plenty of talent and they can perform. And I like that little group called First Aid Kit.”

Ronstadt keeps in touch with many of her musical peers. Randy Newman and Paul Simon each paid her a visit recently. She loves having music in her home, often inviting her nephews to rehearse in her living room and singing along with them in her head. That’s what she misses most about not singing — harmonizing. “It’s like being able to see the city view through the eyes of an eagle,” she says.

If anything, that’s what she hopes people take away from the documentary — not to be afraid to sing, even if you’re not a professional.

“For me, there’s public music, private music and secret music. And secret music is what you do when you’re all by yourself, and everybody has it,” she says. “You should sing in the shower. You should sing in the car. You should sing at the dinner table.”

As for her self-criticism of her voice, Ronstadt insists she isn’t hard on herself — “just accurate.”

“I know there are some things I did that I’m pretty happy about,” she says. “I had a lot of formidable competition. Joni Mitchell and Carole King — I felt like the freshman class and they were the senior class. Fortunately, I’ve never felt that music is a competition, so it doesn’t matter if Joni Mitchell can sing better than I can, or Bonnie Raitt, who can sing rings around me anytime. I just did what I did and tried the best that I could.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.