Movies for grown-ups are in short supply. ‘Ford v Ferrari’ aims to prove they still work

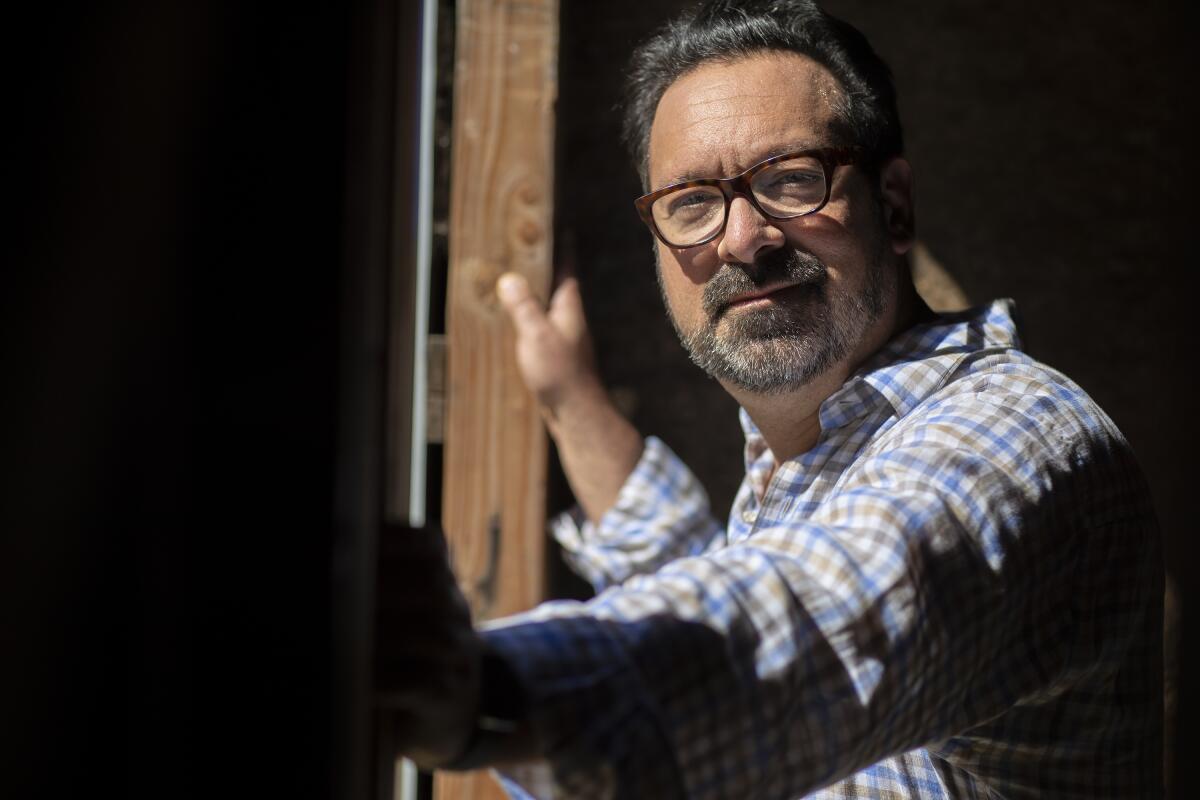

TELLURIDE, Colo. — As a filmmaker, James Mangold has been behind the wheel of almost every kind of movie you can name, from the crime drama “Cop Land” to the western “3:10 to Yuma” to the Johnny Cash biopic “Walk the Line” to the comic-book blockbuster “Logan.” Although the movies have been wildly different, in each one the basic challenge, as he sees it, has been the same.

“The real problem I try to solve across all these genre lines is: How do I hold you as an audience?” Mangold, 55, said on Saturday at the Telluride Film Festival, where his latest movie, “Ford v Ferrari,” made its world premiere. “And how can I take the genre and continue to expand it?”

Set in the high-octane world of car racing, “Ford v Ferrari,” in theaters Nov. 15, chronicles the real-life story of pioneering automotive designer Carroll Shelby (Matt Damon) and maverick British driver Ken Miles (Christian Bale), who were recruited by the staid Ford Motor Co. to try to unseat the perennially dominant Ferrari at the 1966 Le Mans auto race. Anchored by its two leads, the film — the type of old-fashioned, crowd-pleasing adult studio drama that is fast becoming an endangered species — will be closely watched as the very different kind of race that is Oscar season unfolds.

The day after the film’s well-received premiere, Mangold spoke to The Times about how film directors are like race-car drivers, the state of movies for grown-ups, and his genre-hopping journey through Hollywood.

How nervous were you before that first screening yesterday?

We had test-screened the movie, and it had done well, but I didn’t know how it was going to play for the film-festival scene. It’s not an essentially dark film, and there is in the postmodern age a kind of jaundice that people have where if you don’t have something [awful] to say about the world, then why are you saying it? But I think it’s gone well.

Some early reviews have used the phrase “old school” to describe this movie. Do you see it that way?

I love that. If I were a carpenter, I’d love it if you said the quality of my tables is old school. It would mean that there are beautiful joints and that things aren’t just tacked together. I live for that. It’s why I still make movies and have a harder time in television, because what I’m doing requires more time. I love the craft and I love trying to put things together in a way that feels resonant.

What appealed to you about this story from the start?

I’m not essentially a car obsessive, so my response to the story was really connecting to these characters. I had heard of Carroll Shelby, but I didn’t know anything of Ken Miles until I read the script for the first time. But I innately identified with him, and I instantly thought of Christian.

In a weird way, the racing scenes attract all the attention, but the real tough things are the in-between parts. In the race scenes, you’ve got the sound and the engines and the speed and the movement and the obvious stakes. That stuff I can do, and I love doing it in an inventive way. But it’s trying to hold the audience when the stakes are less driving, when you’re in a moment of intimacy and you aren’t being bounced along with music — that’s when I get really excited.

Though this movie is set in the world of auto racing, there’s also a way it could be seen as an allegory for the movie business, with the executives who want to play it safe trying to control the artists who are trying to push the boundaries. How much were you thinking about that while you were making it?

All the time. I saw a lot of parallels. I’ve had the come-to-Jesus meetings with the studio where they’re like, “This element of your movie must change or we’re not making it.” This was also a time in the ’60s when things were less tested. There was no computer modeling. You had to just on a hunch build a car and put a man in it and drive it and see if it works or explodes. Similarly, with movies, I miss a little bit those days when people went on their gut.

That said, this movie really brings home the insanity of driving at such high speeds over hours and hours on a hunch, particularly with the technology they had back then.

It’s crazy. They didn’t even have a roll bar. There was no thought applied to making the [driver’s] cabin safe. That all came later with computers and an understanding of crush patterns and stuff that just didn’t exist at that point.

But is it any more crazy than making movies? Like, what are we all doing? All these endeavors are kind of crazy, but they’re things we’re compelled to do.

Well, when you’re making a movie, you’re less likely to die in a giant fireball.

No, but you die other deaths making movies. [Laughs] There is a kind of body count in movies that is different. It’s competitive and frightening, and the pressure is intense. Whether it’s our own anxieties and neuroses, you do perceive it as a life-or-death struggle. This is what I love about Ken: To do your job well, you have to push all that awareness of the stakes out of your mind. Otherwise you get paralyzed.

This is the kind of big, entertaining drama for grown-ups that used to be a mainstay of the studios and is now becoming more and more rare. I read that an agent told you, “You’d better enjoy this one because it’s the last one you’re going to get to make.” Do you feel that way?

That was said in jest, but they were serious in the sense that the whole business is in a moment of contraction, and it’s very hard to get movies made that don’t have some kind of built-in audience. Movies have kind of gotten segregated into “stupid and fun” or “intense and I’ll wait until home video.” That means that all of the dramas have almost no life theatrically because the audience is waiting to watch them at home. And the only things that are thriving are tentpoles with built-in sell-through or very bouncy, light, frothy things — and even those sometimes have a hard time if they’re too adult-themed.

Modern genre movies have become like a ride at a theme park. You never get close to anything. It’s just intoxicating spectacle. I’m always thinking, what if we can deliver the spectacle and deliver the quality human moments in the same experience? Because if you don’t hold a movie with your characters, you have to keep getting louder and noisier and flying the camera around more just to hold the audience from detaching. When I see those kind of sensory-overload movies, I have a kind of narcoleptic response where I start to spontaneously fall asleep. It’s too much.

I am aware that there’s more at stake now, that if these don’t work they’re not going to make them again. And I think it’s really important that we keep alive the ability to tell original stories.

You’ve had such an eclectic career, bouncing constantly between genres. Do you see a consistent through-line?

I try not to see a through-line because I think it wouldn’t be healthy for me. I think I’m attracted to character. We now get boxed in so quickly, whether it’s by the press or the business itself. We get put in the disco or rock ’n’ roll or rap or country slots in the record store. But so many of the filmmakers I admire moved from genre to genre.

My example always is that Billy Wilder didn’t make a funny film until his 16th film. So how can we even know what we’re good at? Or maybe what we’re good at is different things and carrying these energies back and forth.

We’re at a point now where speculation about a movie’s awards potential starts the second its first festival screening ends. Is it hard to tune that out?

You have to tune it out. That horse race stuff — obviously you guys have to report on it, but essentially every moment you’re talking about who’s ahead and who’s behind, you’re not talking about the movies. You have to get in a bubble and push it all away.

I think I’ve gotten better at that over the years. I’ve had movies that play well, and I’ve had movies that play less well. I’ve had movies that they think are not going to play well and they surprise you, and I’ve had movies that they think it’s going to be a home run and then it isn’t. And once you’ve lived through every one of these scenarios and you’re still here making movies, it makes you a little less frightened. You think, I’ll probably be here tomorrow.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.