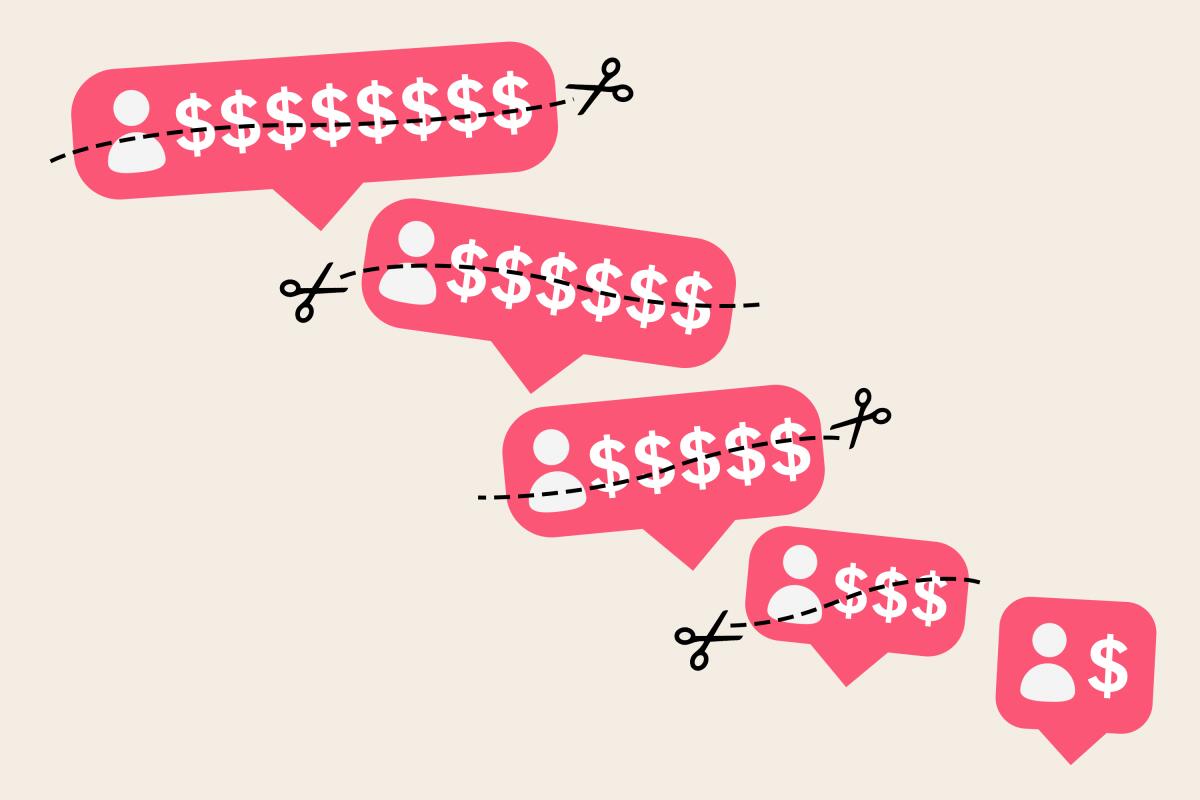

What happens to social media influencers when inflation hits?

At first glance, Jacquelyn Mengel’s TikTok looks like every other influencer video.

She stares directly into the camera, holds up name-brand makeup products and discusses how she feels about each one. It’s a familiar scene on social media: someone trying to sell you something.

Except this time, that’s not what’s going on. She’s telling you what not to buy.

“Another de-influencing video,” explains Mengel, 20, “so that we can all save some money.”

The web personality walks her viewers through a handful of different beauty products she doesn’t think are worth the price tag: an underwhelming shampoo and conditioner, a $20 makeup sponge. It’s hardly anti-consumerist — Mengel suggests a cheaper alternative to each overpriced item — but the talk of belt-tightening seems to have struck a nerve with fans. Her video sits at over 750,000 views.

It’s all part of a trend that’s taken TikTok by storm in recent weeks — “de-influencing” — that finds social media creators calling out trendy products that aren’t worth the cash amid a moment of economic turmoil. And viewers looking to save a little dough are eating it up: Videos tagged #deinfluencing have already been watched 125 million cumulative times.

This might not be what you’d expect from influencers, who — posing on the bow of a yacht or a posh rooftop deck, dripping with designer jewelry and haute couture — aren’t known as a typically frugal bunch.

Yet things may be changing as economic headwinds shift. America is in the midst of a financial slowdown, which some experts say could blossom into a recession, and the influencer economy is hardly exempt. The third-party brands that keep the sector liquid are drawing back their ad budgets. Social media companies have begun to cut staff. And the content people post online is shifting, too, as influencers tout designer brand knockoffs and tech employees document their own layoffs.

As tech giants lay off scores of workers amid a sector-wide downturn, employees who once considered the Silicon Valley companies a safe long-term bet are reconsidering their allegiances.

But the rise of de-influencing videos may be the most foreboding omen of all: a stark rejection of social media’s typically conspicuous consumption.

“It’s what people need to hear right now,” Mengel, who’s based in Salt Lake City, said in an email. She reports making $3,000 to $10,000 a month — about 70% of her income — on the app.

“I definitely think the ‘de-influencing’ trend has sparked due to the recession that seems to be coming,” she explained. “Changing my direction into ‘de-influencing’ or providing more affordable options has actually made my account grow tremendously in the past week.”

Mengel isn’t the only influencer who is pivoting her content in a more economical direction.

Lauren Rutherglen, a Calgary-based TikToker who reviews outfits and beauty products, recently posted a de-influencing video of her own in which she criticized overpriced makeup. She got 205,000 views.

“Consumers online … want to pay for products, especially in our economy right now, that work for them,” said Rutherglen.

In only a few years, the five young Latinos in the Familia Fuego TikTok collective have gone from working day jobs to mixing with Hollywood’s elite.

Influencers say the trend began sometime within the last few months and reached a critical mass in January, propelled by macroeconomic stress as well as a long-brewing backlash against pay-to-play product reviews. (A scandal in TikTok’s makeup community involving allegations of fake eyelashes added more fuel to the fire.)

“There’s a theme of over-consumption when it comes to social media, and I think people are starting to notice just how detrimental it is towards our wallets and the environment,” said Karen Wu, another de-influencer, in an email. “Add in the economic downturn and … consumers are starting to grow tired of the rhetoric that they NEED every viral product they see.”

If de-influencing is a sign of the times, it’s not the only one.

“Dupes,” or knockoff versions of designer fashion products, have become similarly popular during the last month. TikTok videos tagged #dupe have reached 2.7 billion total views, with creators recommending, say, $35 Amazon sweatpants to stand in for a $128 Lululemon equivalent.

“The whole ‘dupe’ trend … it’s just people giving options for higher-end items that not a lot of people can afford under the circumstances of the economy,” said Valeria Fridegotto, a TikToker who’s been posting both de-influencing and dupe videos.

Recent trends in online aesthetics, such as leaving your hair its natural color or rocking logo-less goods, are similarly recession-friendly, influencers say.

The rise in viral trends that cater to viewers with a little less spending money is in part a product of supply and demand. Influencers figure out what their fans want, then make it for them; those who don’t, fall behind.

But the market downturn could also force influencers to cut back in their own lives. Brand deals — the linchpin of for-profit social media — have started to dry up, according to some digital creators.

“It does feel that there was a shift somewhere in the last [12] months as paid opportunities seemingly slowed down,” Los Angeles-based TikTok comedian Leo González said in an email. “Having that in mind has shifted the way I plan financially.”

Scarlett Bloom, who until recently was a porn actor on the subscription-funded adult website OnlyFans, said she’s also noticed a sharp drop in her earnings since the summer.

“I’ve definitely had subscribers straight up tell me they were going to unsubscribe for a while due to them facing financial hardships,” Bloom said in a Twitter message.

Triller, the Century City company, plans to go public later this year even as it faces lawsuits over unpaid bills and breaches of contract.

Media industry experts are forecasting reduced growth in 2023 for the ad industry. Investment in creator-economy startups was, by one count, down 79% year-over-year last quarter. Social networks are, in the name of austerity, cutting back on creator programs. And layoffs at Snapchat, YouTube, Twitter, Pinterest and Meta (which owns Facebook and Instagram) paint a portrait of a struggling industry, even if some of that burn-off is the result of overeager hiring during the pandemic.

Alyssa Kromelis, owner of the boutique digital marketing agency XO Social, said that a lot of her clients are drawing back their influencer marketing campaigns. The pandemic was a boom-time for her, she explained, but conditions have worsened since the summer.

“When eggs are $8 a dozen, people can’t be spending $45 on a highlighter,” Kromelis said. “It doesn’t make economic sense.”

The marketing firm Social Currant, which focuses on connecting influencers with nonprofits and political advocacy brands, has also noticed a contraction.

“We’ve had a few clients [with] affected budgets around, like, ‘Hey, we’re pausing spend for Q1 and want to pick up in Q2,’” said Social Currant founder and chief executive Ashwath Narayanan. But other clients, he added, are embracing influencers as a way to diversify their marketing strategies during a period of heightened stakes.

Sam Pocker, known by his handle @FastFoodLegend, is a minor celebrity on TikTok for his avant-garde gross-out videos. But chasing social media stardom comes at a cost.

Representatives from several influencer management firms said reports of a downturn in the sector are exaggerated, and suggested that even if ad budgets get cut elsewhere, social media marketing can offer a higher return-on-investment than more traditional ad buys.

“Our creators are busier than ever,” said Brian Nelson — co-founder of the Network Effect, which works with short-form video creators on TikTok, Instagram and elsewhere — in an email.

Some creators are optimistic, too. Mariale Marrero and Stephanie Ledda, two influencers who make content about makeup and beauty products, said business remains steady, thanks in part to recent products they’ve launched: a makeup collection from Marrero, a perfume from Ledda.

Kimberly Duman, a managing director at Marrero and Ledda’s management firm TalentX, said that she hasn’t seen the price tag on brand deals shrink — but there has been a decrease in how many influencers a given brand works with.

“Even when the economy is bad, people are home playing more video games; they’re cooking for themselves more; they’re doing more for themselves; they’re streaming more entertainment,” Duman said. “We encourage clients to think about those things … and how they can incorporate that into their content.”

Indeed, a recession could present new opportunities for some influencers.

Julia Belkin, who runs an account called “Freebies and More” on TikTok and Instagram, is about as well-situated for that eventuality as a content creator can be.

Her niche? Deal-hunting videos.

“Since, I’d say, the beginning of January, my viewership shot through the roof,” said Belkin, who currently has 63,000 followers on Instagram and 1 million followers on TikTok. “People love free stuff right now.”

Starting off as an extreme couponer, Belkin has now been posting on social media about free and discounted products for eight years. In that time, she’s seen two periods of sharp growth: once at the start of the pandemic and now as viewers seek DIY homesteading hacks, gig-economy side hustles and, of course, free merch.

“In times of uncertainty, pretty much no matter what that uncertainty is, people tend to really gravitate toward deal-finding,” Belkin said.

“I’m in a relatively recession-proof, quote unquote, industry.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.