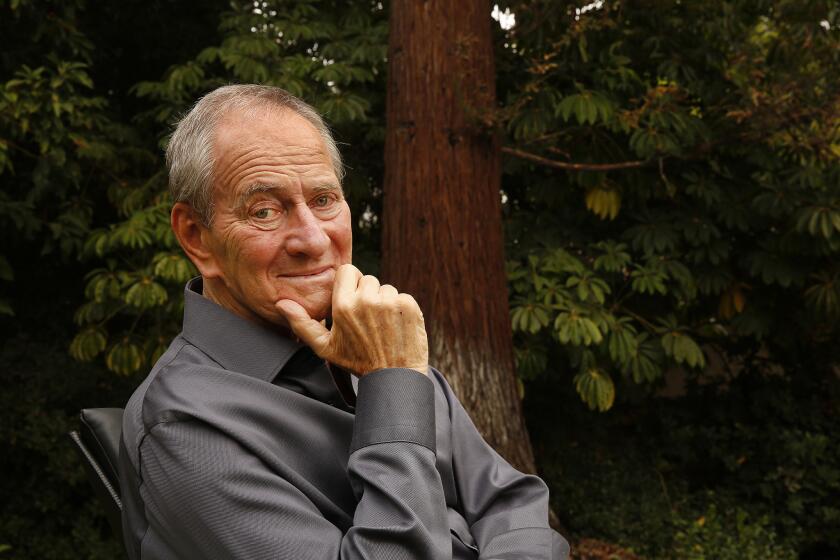

Owen Roizman, ‘French Connection’ and ‘Exorcist’ cinematographer, dies at 86

Five-time Oscar nominated cinematographer Owen Roizman, who shot landmark films including “The French Connection,” “The Exorcist,” “Network” and “Tootsie,” has died. He was 86.

The American Society of Cinematographers confirmed Saturday that Roizman had died after a long illness.

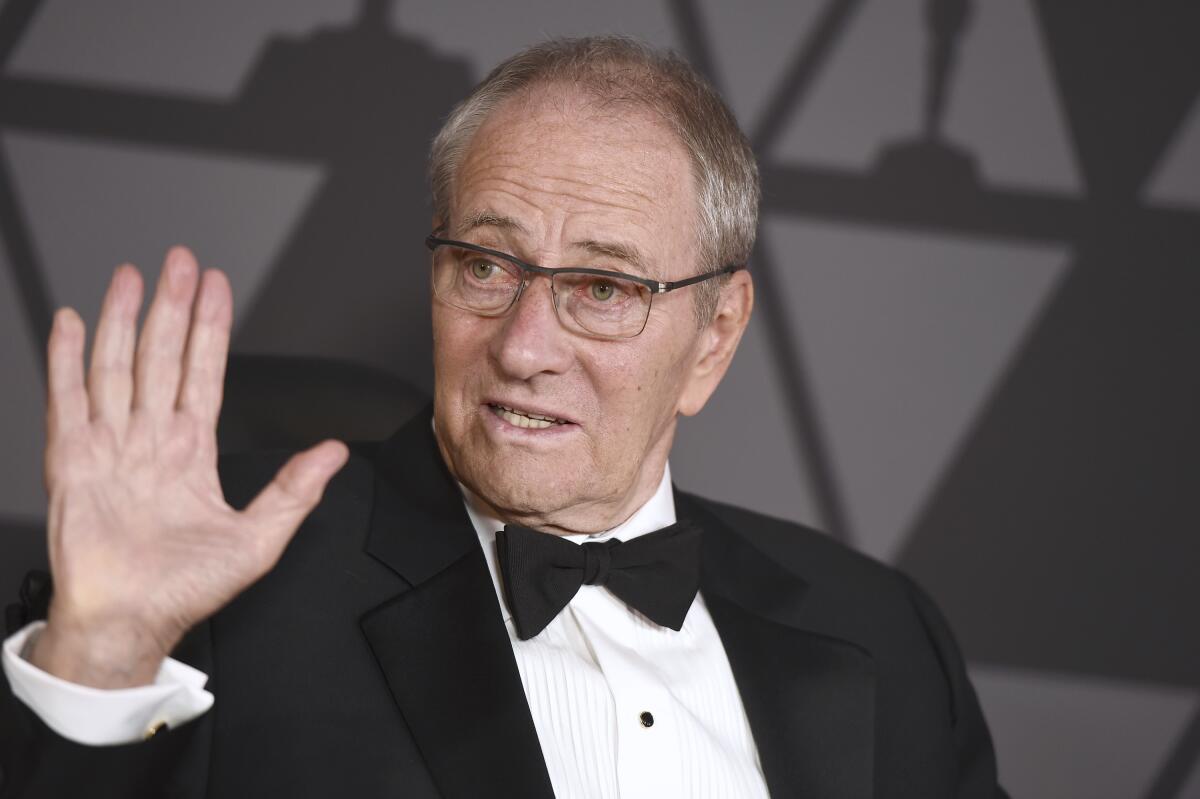

New York-born Roizman, who died at his home in Los Angeles, was given an honorary Oscar for his career achievements in 2017, having retired from the film business in the 1990s without yet taking home one of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences gold statuettes, despite the multiple nominations.

Roizman was known for his collaborations with Sydney Pollack and William Friedkin. His film work included “Play It Again, Sam,” “The Heartbreak Kid,” “Three Days of the Condor” and “Wyatt Earp.”

He received his first Oscar nomination for 1971’s “The French Connection” — his second film — which starred Gene Hackman as a violent police detective. After filming the influential Friedkin-directed neo-noir crime thriller, including its famed car chase sequence, Roizman became known for his “gritty” documentary style, a designation he found amusing, given the wide variety of genres in which he excelled.

“Immediately after ‘The French Connection,’ I got labeled as a gritty New York street photographer, which I thought was very funny because I had never shot anything like ‘The French Connection’ before that,” Roizman told the Los Angeles Times in a 2017 interview. “I got a kick out of that. My primary goal was always just to serve the story and to tell the story visually the best way I knew how.”

Roizman, born in Brooklyn on Sept. 22, 1936, grew up with camerawork in his blood.

His father, Sol, was a cinematographer for Fox Movietone News. His uncle Morrie was a film editor. After graduating from Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania, he began his career as an assistant cameraman in commercials and worked his way up to cinematographer.

He got his break in a low-budget 1970 film, “Stop,” that was seen by almost no one — except for some key people — Friedkin and “The French Connection’s” producer Phil D’Antoni, who liked his work.

“The French Connection” was notable for its use of available outdoor light, giving it its real-life feel. The seminal chase scene veers through the mean streets of New York as hard-nosed Det. Popeye Doyle (an Oscar-winning Hackman) commandeers a civilian car and tries to keep up with the hit man who is attempting an escape on an elevated train.

“It was done in two different ways,” Roizman told The Times in 2011. “Three cameras were used inside the car, including a camera on the dashboard that would look out through the windshield and one over the driver’s shoulder. From the outside, we had five cameras. We broke it down to five stunts, and the rest of it was just bits and pieces. For each of the stunts we had five cameras set up at different angles to cover it all.”

Roizman told American Cinematographer that “the biggest problem there was trying to match because the light was changing constantly. As we’d run along the track, another train would pass and block out the light. Or we’d go between tall buildings and that would cut down the light in the middle of a scene.”

His work on Friedkin’s 1973 film, “The Exorcist,” is remembered for bringing a lived-in realism to the supernatural horror genre.

One of the challenges of filming the climatic exorcism scene was to convey the freezing temperature of the child’s bedroom by getting the actors’ breath to show onscreen, he said to American Cinematographer.

To get the believable effect, the filmmakers created a replica of the room and refrigerated it.

“A system was developed that could refrigerate the room quickly to any temperature from zero to 20 below,” Roizman said. “The breath showed up fine at zero, but Friedkin wanted the actors to really feel the cold because he felt that would help their acting. An actor on his knees for 15 minutes at 20 below zero is really going to feel cold. It worked out very well.”

The film earned Roizman his second Oscar nod.

He moved from New York to Los Angeles in 1976, later establishing his own TV commercial production company, Roizman & Associates.

His other Oscar-nominated work spanned several decades, including Sidney Lumet’s TV news satire “Network” (1976), Pollack’s Dustin Hoffman comedy “Tootsie” (1982) and Lawrence Kasdan’s western “Wyatt Earp” (1994). “The French Connection,” “The Exorcist,” “Network” and “Tootsie” were all nominated for best picture as well. “The French Connection” won.

In 1997, he received a lifetime achievement award from the American Society of Cinematographers.

He said he never regretted turning down any film — even “Jaws,” the industry-changing Steven Spielberg summer blockbuster from 1975.

“We spoke for maybe three hours on the phone, and I really liked him — and I still to this day love the guy,” Roizman said. “But what he didn’t know is that I was thinking to myself the whole time, as he was describing the story to me, ‘Jesus, a shark terrorizing a town on Long Island — that means going on a boat a lot.’ I get seasick. So that didn’t sound too inviting to me. So I turned it down really for that reason.”

He is survived by his wife, Mona Lindholm and his son, Eric Roizman, who pursued his own career behind the camera, working on “Wyatt Earp” with his father, in addition to other pictures.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.