How the gay rights showdown threatens Disney’s unprecedented self-rule in Florida

For more than half a century, Walt Disney World has effectively operated as it own municipal government in central Florida.

A 1967 state law established the Reedy Creek Improvement District, giving Walt Disney Co. extraordinary powers in an area encompassing 25,000 acres near Orlando where the sprawling themed resort now sits. The law grants Disney a wide range of abilities, including the power to issue bonds and provide its own utilities and emergency services, such as fire protection.

The law is partly what convinced Disney to come to Florida in the first place and allowed it to flourish and become the state’s largest private employer, with nearly 80,000 jobs.

Now, though, that special designation is under serious threat as Gov. Ron DeSantis and Republican legislators wage an escalating culture war against Disney over the Burbank-based entertainment giant’s opposition to legislation that it considers to be anti-gay.

Current conflict is the latest to reveal underlying tensions that have existed between Disney and religious conservatives for decades as it has embraced the LGBTQ community.

The Florida House of Representatives on Thursday approved a bill that would dissolve Walt Disney World’s private government. The action came a day after the Florida Senate passed the bill that would dissolve all independent special districts established before 1968, including Reedy Creek. State senators voted 23 to 16 in favor of the bill during a special session of the state Legislature.

“Disney is a guest in Florida,” Republican Rep. Randy Fine, who sponsored the bill, tweeted on Tuesday before the vote. “Today, we remind them.”

DeSantis, who had previously backed legislative efforts to revoke Disney’s special privileges, on Tuesday expanded the special session to consider the elimination of the district. The bombshell announcement dropped just hours before the special session that was originally intended to focus on congressional redistricting, which has also been controversial. The lawmakers also approved DeSantis’ redistricting map that favors Republicans.

A Disney representative did not respond to a request for comment.

DeSantis and conservative commentators have spent weeks blasting Disney for its opposition to Florida’s Parental Rights in Education law, which the governor signed last month. Disney has said its “goal as a company is for this law to be repealed by the legislature or struck down in the courts.” The company also pledged to “pause” all political donations in the state as it reevaluates its approach to advocacy.

Disney’s Chief Executive Bob Chapek first voiced opposition to the bill, nicknamed “Don’t Say Gay” by its opponents, after receiving blowback from employees. Chapek, who initially resisted getting involved to avoid Disney becoming a political football, spoke out only after the bill passed the state Legislature.

The Parental Rights law bans classroom instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity in kindergarten through Grade 3 “or in a manner that is not age appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.” LGBTQ activists say the law amounts to a homophobic attack on queer youth.

The speed at which the legislature has acted against Disney reflects the growing tension between the company’s outwardly progressive stance on social issues and Florida’s conservatives, particularly DeSantis, who many observers believe will mount a presidential run in 2024.

Some observers had seen the rhetoric as mere grandstanding. But proving a point against Disney may matter more now to DeSantis’ base than the traditional business-friendly aims of economic conservatives, analysts told The Times.

“I thought that this was an effort to shoot across the bow and cause Disney to steer in a slightly different direction, and that wiser minds would prevail,” said Richard Foglesong, author of “Married to the Mouse: Walt Disney World and Orlando.” “That could still happen. But what’s really behind this is the culture war. Things have changed. This is not the Republican Party of the Bushes.”

But aspects of how the dissolution of the Reedy Creek Improvement District would work are still unclear. So is the expected impact on Disney itself and the counties where it operates.

Why does Disney have these special powers?

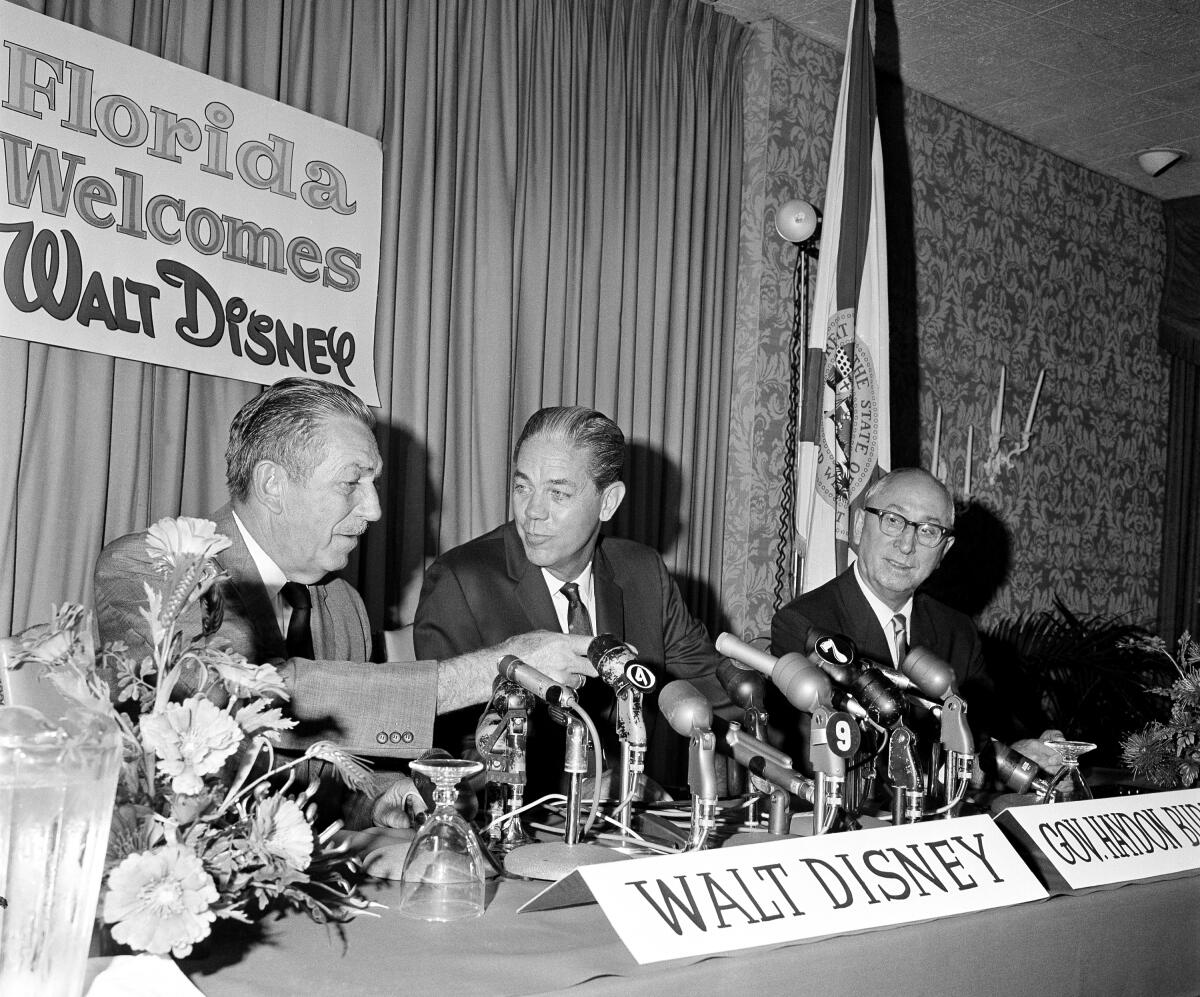

When brothers Walt and Roy Disney were looking to create another theme park on the East Coast, they took with them lessons from operating Disneyland in Anaheim, where it opened in 1955. Dealing with local regulations and government building inspections was a hassle. Disney wanted a way to achieve its sprawling ambitions without being so encumbered by municipal bureaucracy. The original idea for Epcot, in fact, was that it would essentially function as its own city.

And so the company worked with lawmakers to establish the Reedy Creek Improvement District. Walt Disney died in 1966, the year before the Reedy Creek law passed and a few years before Walt Disney World Resort opened in 1971.

The district, spanning roughly 40 square miles in both Orange and Osceola counties, provides everything from fire protection and emergency medical services to water systems, flood control and electric power generation. Its boundaries include four theme parks, two water parks, a sports complex, 175 miles of roadway, the cities of Bay Lake and Lake Buena Vista, utility centers, more than 40,000 hotel rooms and hundreds of restaurants and retail stores, according to its website. A five-member board of supervisors, elected by landowners, governs the district.

Its creation allowed Disney to transform acres of uninhabited pasture and wetland into a massive driver of tourism.

The powers granted were broad, making it much easier to move forward on building something like, say, the 183-feet tall Cinderella Castle, experts said. The district’s charter left open the possibility of Disney building its own airport or nuclear power plant if it wanted to. This was done to anticipate whatever needs might come up.

“They knew they were going to have one shot at these powers, because Florida needed Disney more than Disney needed Florida,” Foglesong said. “They could get these powers at the opening, but they weren’t confident that they could add to their powers down the road. And so it was understandable that attorneys, I have no doubt, said, ‘Let’s get all we can now.’”

How would Reedy Creek be dissolved?

Though the Florida Legislature is moving rapidly, the end of Reedy Creek wouldn’t happen immediately. Its dismantling would take effect June 1, 2023, along with that of a few other districts, giving Disney and the state about a year to resolve their issues. It also leaves the door open for special districts affected by the legislation to be reestablished.

Some lawmakers who oppose the move against Disney question whether the Legislature has the authority to unilaterally eliminate the company’s powers. Florida House Rep. Carlos Smith, who opposes the bill targeting Reedy Creek, tweeted an image of a section of a Florida statute indicating that dissolving an active special district would require the votes of landowners in the area. Disney holds the vast bulk of the voting power in Reedy Creek.

“The knee-jerk, vindictive, un-researched and reckless GOP plan to ABOLISH Disney’s #ReedyCreek district also appears to be ILLEGAL,” Smith said in a Twitter post accompanying the photo.

Disney’s money has controlled Florida politics for more than 50 years. Now the politicians are showing their ingratitude.

Florida journalist Mary Ellen Klas, of the Miami Herald, reported that state Sen. Linda Stewart, whose district includes Walt Disney World, told her she’d had discussions with Disney executives who concluded that the Legislature can’t dissolve the district without the approval of voters.

Aubrey Jewett, political science professor at the University of Central Florida, said the pace of legislative action — in a special rather than regular session — has created tremendous uncertainty over what lawmakers can actually do and what happens next.

“If this was really about good public policy, then it would have been done through the regular legislative process,” Jewett said. “But that clearly was not their intent. And so they’ve acted so quickly that we don’t really know a lot about the legalities.”

How would this affect Floridians and Disney?

Some lawmakers say the decision, if it takes effect, could create a significant financial hit for the counties affected by the Reedy Creek district. Disney finances the services the district provides, which would normally be paid for by local municipalities. Disney effectively charges itself property taxes to finance these services. For law enforcement, Disney pays the Orange County Sheriff’s Office.

If the district is dismantled, those responsibilities could fall to local municipalities and taxpayers, experts said. So could the district’s debt-load. The district’s long-term bonded debt totaled more than $977 million as of September, according to Reedy Creek’s annual financial report. State Sen. Stewart tweeted that removing the district “could transfer $2 Billion debt from Disney to taxpayers” and could have “an enormous impact on Orange & Osceola residents.”

Yet the ultimate effect on taxpayers remains unclear, as the government in its haste has not produced a thorough review of the financial impact. Rep. Fine speculated to Insider that taxes could go down as a result of “eliminating a layer of government.” The state Senate’s analysis of the bill simply says it would have an “indeterminate fiscal impact” on local governments that “will assume the assets and indebtedness of an independent special district dissolved by the bill.”

The fallout for Disney is also uncertain. While Disney pays for its own services in the district, it does get some benefits. It can issue municipal bonds, which get a lower interest rate than corporate debt. Disney is also exempt from certain fees and may save money by contracting local sheriff’s deputies, according to Foglesong. But the main benefit over the decades has been the flexibility the designation affords Disney.

“They’d rather have it their way, where they can do things for themselves, rather than have to depend upon government,” Foglesong said.

Disney will probably fight back. It can’t pick up Walt Disney World and move it to a friendlier state, the way it can threaten to take the production of Marvel movies out of Georgia.

However, the company has announced that it is moving some 2,000 jobs, including theme park attraction designers known as Imagineers, to central Florida — a decision it could renege on. Then there’s Disney’s history of financial contributions to local politicians, which totaled roughly $50 million from 1996 through 2021, according to official campaign disclosures.

Those combined factors could give the company some leverage. But that may not stop a political movement that wants to punish Disney for being a “woke” corporation. “Even though there might be really good reasons why we shouldn’t have Disney control three local governments, the process that’s being used to dismantle it is a shambles,” Jewett said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.