For Karl Lieberman, chief creative officer at ad agency Wieden + Kennedy in New York, Super Bowl Sunday is not the football holiday it is for most Americans.

Lieberman’s shop will have five commercials running in the NBC telecast of Sunday’s game between the Los Angeles Rams and the Cincinnati Bengals at SoFi Stadium in Inglewood. His clients include Anheuser-Busch, Amazon Prime and TurboTax.

Instead of enjoying the contest while downing a few Bud Lights, he’ll be hearing from the war rooms and response teams set up to monitor real-time reaction online to the agency’s work that appears during the game.

“I wouldn’t compare us to doctors, but it’s like we’re on call as brand representatives 24 hours a day,” Lieberman said.

Such is life for today’s advertising executive in the shifting television landscape upended by the exodus of young viewers who prefer watching video entertainment online — preferably without commercial interruptions.

Thirty-second commercials — especially during the Super Bowl — have a tall order these days. They need to be conversation starters that can engage consumers who will spread advertisers’ messages on social media, garnering impressions on top of the massive audience watching the game.

“The TV commercial used to be the end of our process,” Lieberman said. “The process started with insight, research and production — months and months of work. And that thing went out into the world that was effectively the first and final chapter of the show. Now, it’s sort of reversed. The spot is now seen as a first chapter — a catalyst to sort of launch a whole ecosystem that people in the real world can then see and interact with.”

The Super Bowl has been an advertising showcase since Apple ran its famous “1984” commercial introducing the Macintosh personal computer 38 years ago. The full impact of “1984” wasn’t known until sales of the Macintosh far exceeded Apple’s expectations over a couple of months.

Now, the response to whether a commercial is working is immediate, especially when it goes out to an audience of nearly 100 million people, many of whom are on their smartphones.

“It’s really important to understand what your consumers and fans are saying,” said Karen Costello, chief creative officer for ad agency Deutsch LA. “The Super Bowl puts a finer lens on that.”

Despite the challenges facing advertisers, demand for TV spots during the Super Bowl shows the 30-second commercial still has plenty of juice. This year, advertisers spent as much as $7 million for a spot on NBC’s telecast — which sold out last week — up from the $5.5 million CBS commanded in 2021.

Last year, the Super Bowl was watched by 96.4 million viewers, according to Nielsen data, a 14-year low for what has been TV’s most watched annual event since its inception. The gridiron showdown still towers over every other program, as does the NFL in general.

Even with a decline in audience, however, the cost of Super Bowl ads keeps escalating. Emerging advertising categories and product introductions looking to create instant name recognition — this year its cryptocurrency companies and electric vehicles — drive up the price. NBC has said there are 30 first-time Super Bowl advertisers in this year’s game, compared to 26 last year and just seven in 2020.

The higher costs coincide with a greater creative challenge. Along with having to produce an engaging, entertaining commercial that will score well on USA Today’s “Ad Meter” and earn added exposure on network morning shows the following day, ad agencies now have to navigate the habits of TV viewers, which have changed dramatically with the advent of Netflix, Disney+ and other streaming services.

Live TV viewing, where viewers sit through commercials, has declined dramatically over the last decade as streaming siphons viewers away who want to watch shows on their own schedule. Nielsen data shows the number of adults under age 50 who watch live TV has dropped 45% over the last five years.

“Every time there is an extra layer of choice added, people are going to run in the opposite direction of advertising,” said Joe Glennon, an associate professor at the Klein College of Media and Communication at Temple University in Philadelphia.

The dynamic has led to a change in approach to creating commercials, especially those made for the Super Bowl, when the extraordinary price for airtime makes delivering results a must.

“The big mind shift is you have to come from the perspective that people are no longer OK with being advertised to,” Lieberman said.

NBC Sports chief Pete Bevacqua says parent Comcast achieved its goal of boosting its Peacock platform with the Olympics despite “curveballs.”

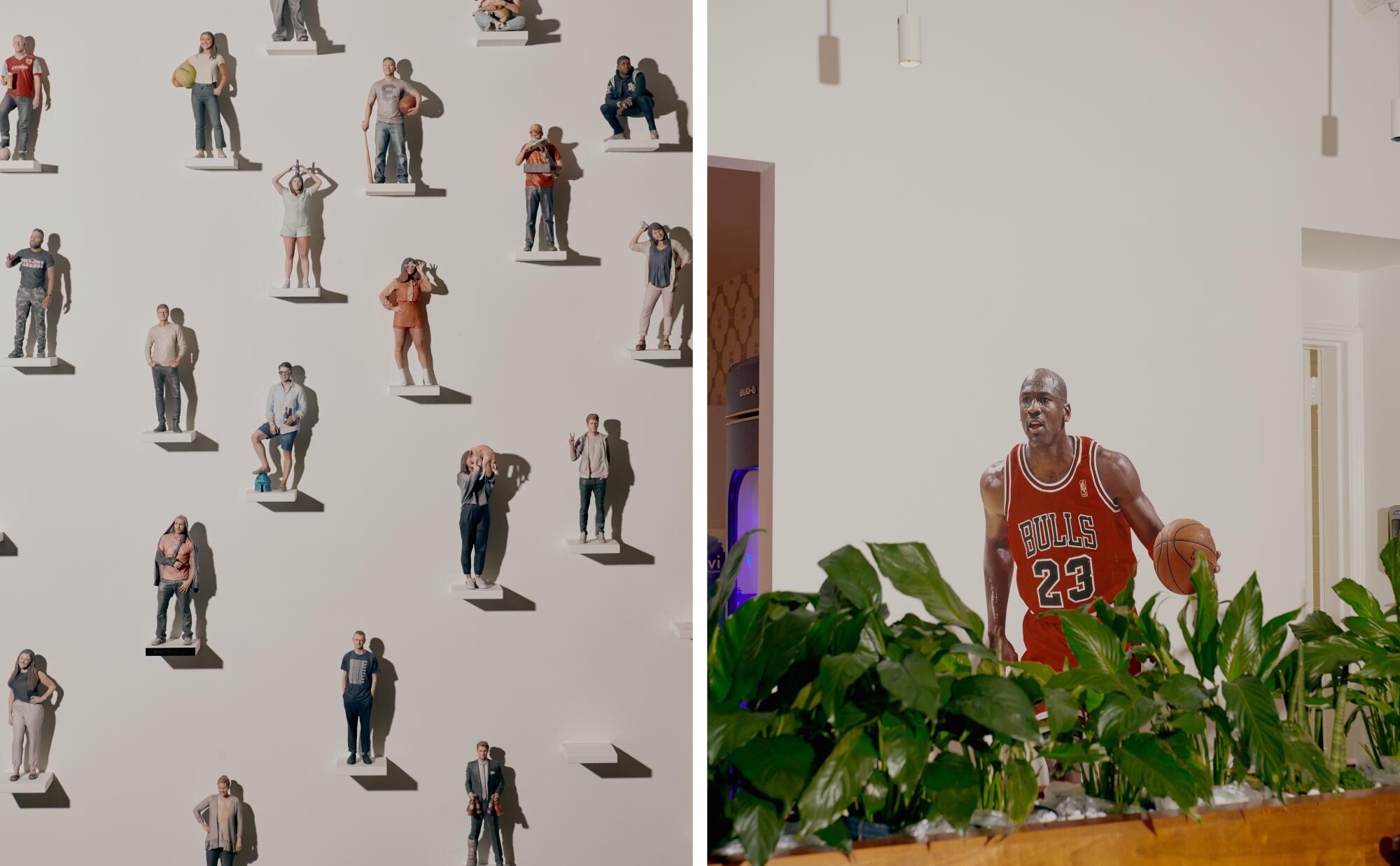

Getting consumers involved in an ad can help. Two years ago, Wieden + Kennedy produced a Super Bowl pregame commercial for McDonald’s that displayed trays showing the favorite fast-food orders of celebrities such as Kanye West, Millie Bobby Brown and Keith Urban.

When the ad aired, the agency solicited viewers on Twitter and other platforms to submit their own favorite orders. The social media team responded, posting images of the requested trays, using combinations prepared in advance or Photoshopped on the fly. The tactic gave consumers a direct personal connection to what they saw in the commercial that they then shared with friends.

Frito-Lay had one of the most popular commercials in last year’s game when it featured Mila Kunis, Ashton Kutcher and reggae singer Shaggy. It used Shaggy’s infectious 2000 hit, “It Wasn’t Me,” as Kunis tried to explain away an empty bag of Cheetos Crunch Pop Mix.

Frito-Lay’s ad agency, Goodby Silverstein & Partners of San Francisco, used shorter versions of the 60-second TV spot — some as short as six seconds — to run across streaming websites such as Hulu and Amazon Prime and social platforms Instagram and Facebook. Shaggy cut a version exclusively for Spotify.

Snapchat users were able to play with virtual reality Cheetos and use the app to get access to a free bag. Consumers were also invited to do their own “It Wasn’t Me” routines in a TikTok challenge.

“You’ve got your boomers and Gen X, who are definitely locked in and watching the commercials as they are running live on TV,” said Margaret Johnson, a partner at GS&P. “But then you’ve got millennials and Gen Z viewers, who are a little more distracted. They’re multitasking. They’re on their phones. So you need something for everyone.”

Kirsten Rutherford, executive creative director for TBWA\Chiat\Day LA, said many Super Bowl advertisers now expect the added value of social media buzz as part of the package of a Super Bowl investment.

“If you tell a great story, the consumer is going to amplify that story and absolutely share their brand love,” said Rutherford, whose agency will have a spot for QuickBooks running in this year’s game. (The preview features a cat learning to sing DJ Khaled’s “All I Do Is Win.”)

TBWA\Chiat\Day’s New York office scored with a spot in the 2021 telecast in which viewers were asked to go on Twitter and guess the number of Mountain Dew Major Melon bottles in a spot featuring actor and WWE star John Cena. The first to guess right, out of nearly 1 million entries, earned a $1 million prize. Cena popped up in GIFs with messages responding to contest entrants for the rest of the night.

Glennon said his advertising students respond especially well to the work they see on social media because they feel connected to it, as the power to create content with a smartphone is part of their daily lives.

“While nobody is excited by an emu selling insurance, the students are very excited by what influencers are doing on different platforms,” Glennon said.

Teasing Super Bowl ads on social media has become commonplace for advertisers looking to promote their spots ahead of the game.

Deutsch LA is credited with pioneering the practice in 2011, when it released its crowd-pleasing Volkswagen Passat spot, featuring a kid dressed up as Darth Vader, on YouTube days before showing it during the game.

This year, GS&P used Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Instagram account to promote a Super Bowl spot for automotive client BMW. The post looks like a poster for an upcoming Schwarzenegger film with the actor playing Zeus, the Greek god of lightning.

The Instagram post received 1.7 million likes and fueled speculation that there is a new Schwarzenegger movie in the works. But the action star and former California governor will be playing the role alongside Salma Hayek Pinault as Hera in a spot for BMW’s new electric vehicle.

The motivation to reach younger consumers on alternative screens has also affected commercial production.

“As you’re looking at [the shot] through the monitor, you have different frames marked out so you can kind of see what the cropping would look like on different social platforms,” Johnson said.

The need to create more content beyond the 30-second commercial is one reason Deutsch LA has an in-house production facility called Steelhead that can handle a range of projects, from full-scale film shoots to TikTok videos.

It seems like a lot of additional work to cater to young viewers who are resistant to advertising. But Costello believes the myriad of viewing choices has simply made the audience more discerning.

“They don’t hate commercials; they just hate bad ones and hate ones that aren’t entertaining or useful in some way,” Costello said. “I don’t think as a generation they reject the idea of brands messaging them. I just think their standards are quite high. They’re incredibly savvy as consumers of content.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.