Meet the archivist who saved the historic footage that became ‘Summer of Soul’

In 2003, film archivist Joe Lauro took a trip to Copenhagen to see his longtime friend Karl Knudsen, owner of the jazz record label Storyville.

During the visit, Lauro helped Knudsen sift through the records and films he’d accumulated over a long career. They came across a 16-millimeter film print of a TV show titled “Harlem Festival” that was sold to foreign broadcasters in the early 1970s.

“I said, ‘Karl what the hell is this?’” Lauro recalled in a recent telephone interview from his home in Sag Harbor, N.Y. “We looked at it, and he told me the story, and I said, ‘Wow.’”

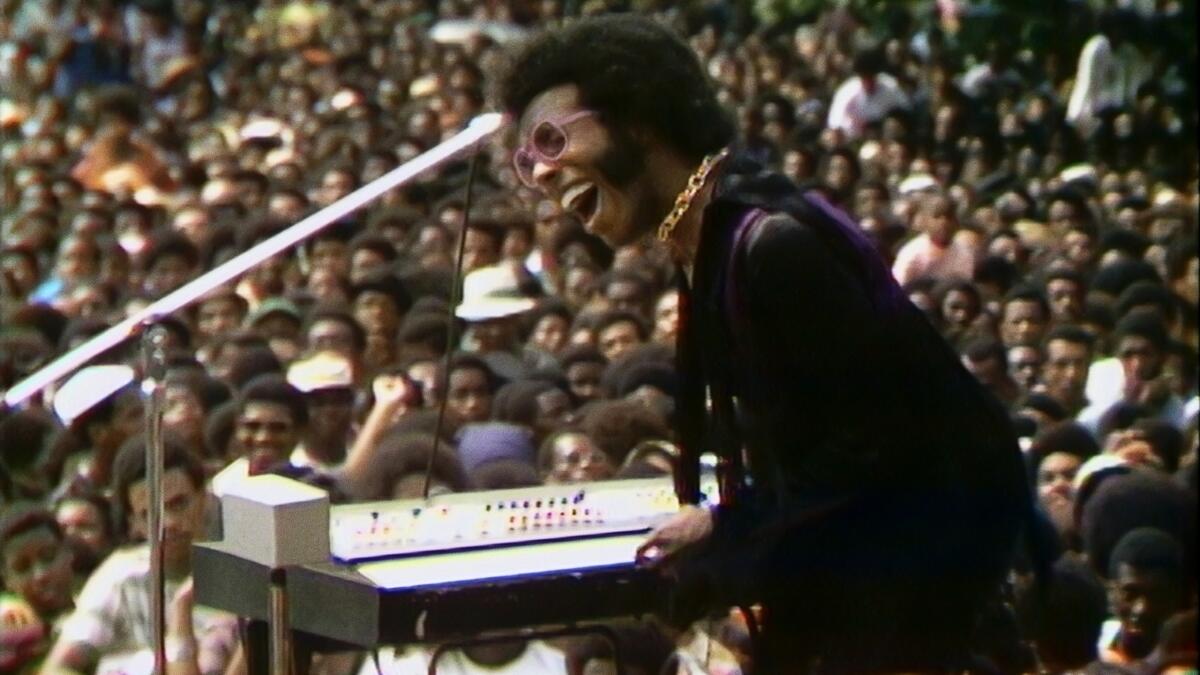

What they saw were performances of many of the top soul and gospel music acts of 1969 in front of large crowds at what is now known as Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem. They were highlights of the Harlem Cultural Festival, six summer-weekend open-air concerts that featured a staggering array of talent, including Stevie Wonder, the Staple Singers, Sly & the Family Stone, B.B. King, Mahalia Jackson, Max Roach, the 5th Dimension and Nina Simone.

At the time, the concert series was overshadowed by the massive gathering 100 miles north in Bethel, N.Y., where the three-day Woodstock rock music festival shut down the New York State Thruway. In the ensuing years, the remarkable festival was largely forgotten. That is, until this year, when Searchlight Pictures released “Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised).”

Directed by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, the documentary is a portal back to a turbulent era when racial tensions were high as the Black community was still raw over the 1968 assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. The movie won the audience prize at the Sundance Film Festival and is a potential Oscar nominee.

The shorthand used by the filmmakers to describe the surprising obscurity of the footage is that it sat for 50 years in the basement of the home of TV director Hal Tulchin, who’d videotaped the concerts and desperately wanted to get them in front of a wider audience.

But the Harlem Cultural Festival’s journey to the screen was far more circuitous and might not have transpired at all without Lauro, although you won’t see his name in the end credits of “Summer of Soul.”

“The film is great, and it needed to come out,” Lauro said. ”But the back story is really different than the way it has been presented.”

The Brooklyn-born Lauro, 66, is the head of Historic Films in Greenport, N.Y. His company is one of a handful of small independent archive houses that specialize in locating, licensing and managing music performances in vintage TV shows and films.

Although large studios and networks have their own archive facilities or hire large outfits such as Iron Mountain Entertainment Services to maintain their content libraries, Historic Films is a repository for the many TV shows and movies made independently and owned by the creators or their estates.

Business is brisk for the archival company as movies, TV and recording industries dig deeper into their past.

Lauro came of age in the 1960s, the musically rich decade when the country rocked to the Beatles, Bob Dylan and the soul sounds of legendary record labels Motown and Stax. He also developed an affinity for early jazz and blues, collecting 78 rpm records. He has 20,000 recorded before 1935, including rarities by Bessie Smith.

His passion and skill for hunting down rare records served him well in the business he launched in 1991. He built his company’s library by poring over old copies of TV Guide for information about music programs that proliferated in the 1960s and ’70s. He tracked down their owners, often pulling tapes and film reels out of storage facilities and ad agency closets.

Once the original films or tapes are restored and digitized, Historic Films licenses clips to documentary makers or TV producers, splitting the fees with the shows’ original owners. In some cases, it acquires the footage outright.

The company manages or owns 50,000 hours of material dating to 1895. The collection includes “Show Time at the Apollo,” a 1955 series that featured such artists as Sarah Vaughan and Dinah Washington, and “Rainbow Quest,” a 1960s program hosted by folk singer Pete Seeger. It also offers “The Red Skelton Show,” the long-running CBS variety hour where the Rolling Stones made their first U.S. TV appearance, and “The Ed Sullivan Show,” where The Beatles played before an audience of 73 million TV viewers in 1964.

Lauro also salvages locally produced music programs from cities around the country, including several that specialized in presenting Black artists and gospel music.

Clips from the Historic Films library have made their way into hundreds of TV specials and documentaries, including Ken Burns’ epic series on country music and jazz for PBS; “No Direction Home,” Martin Scorsese’s 2005 opus on Dylan’s career; and original exhibits at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland.

Lauro wanted to provide the Harlem Cultural Festival performances to filmmakers as well. “We keep the material alive,” he said. “When people don’t see this stuff, it gets forgotten forever.”

After Lauro found the Harlem Festival TV show in Copenhagen, he located Tulchin, whose name was on the film reel.

The two met for lunch near Tulchin’s home in Bronxville, N.Y. Lauro learned that the retired show business veteran, who made TV specials and commercials in the 1960s and ’70s, shot 40 hours of videotape at the Harlem Festival. None of it had been seen since some of the performances were shown on two hour-long network TV specials on ABC and CBS in 1969, and several programs offered to overseas broadcasters in the early 1970s.

“When I approached Hal, he was so happy that anyone cared,” Lauro said.

In 2004, Tulchin signed an agreement to have his footage represented by Historic Films. Lauro had copies of the tapes trucked out of Tulchin’s home to Historic Films, where they were digitized and cataloged. The company began licensing clips of performances, including five songs of Simone’s set for a DVD released by Sony.

Lauro also wanted to help Tulchin realize his decades-long dream of turning the festival footage into a feature film akin to the 1971 Oscar winner “Woodstock.” Lauro developed a “Harlem Festival” project with Robert Gordon, a Memphis, Tenn.-based writer and filmmaker whose credits include documentaries on Stax Records and blues great Muddy Waters, and director Morgan Neville, who would earn an Oscar for his 2013 documentary “20 Feet From Stardom.”

The trio put together a $450,000 budget and cut an 11-minute trailer. In 2007, they began pitching companies for a distribution deal. “We got press,” Lauro said. “We announced it to the world.”

Robert Fyvolent, then a lawyer working for Newmarket Films, recognized the quality and historic importance of the footage and was eager to make a deal for the company, according to Gordon. Lauro recalls they received a $1-million offer.

But according to Gordon, Tulchin began to make new demands during the negotiations.

“As we closed the deal on the feature film, Hal said, ‘I don’t just want it as a film. I want a DVD series,’” said Gordon. “He wanted it in the contract. To Fyvolent’s credit, he rolled with the punches and wrote it. But Hal kept on throwing axes at the deal.”

The contract was never signed. “I did not take it well at the time,” Gordon said.

Lauro’s impression was that Tulchin wanted more money. But Gordon believed his response was more complicated.

“I think Hal had a psychological attachment to the desire for getting the film made,” said Gordon. “Realizing that desire was less important. He was going to make a lot of money, and he was going to see his dream realized. In my opinion, I think it scared him.”

Tulchin split with Historic Films when his agreement with the company expired in September 2007. He later signed a deal with Fyvolent, who’d left Newmarket, to represent him.

It would take more than a dozen years to land a deal for a Harlem Cultural Festival film, which Tulchin would never see. When Tulchin died in 2017, his New York Times obituary detailed the seemingly quixotic effort to get his “Black Woodstock” made.

Earlier this year, Fyvolent and producer David Dinerstein sold the project to Searchlight, with Questlove attached as a first-time director. The drummer for the Roots is a passionate music expert, and his involvement brought attention to the film’s vintage performances.

In initial stories about how the footage found its way to screens in 2021, Lauro’s role was not mentioned. More recently, however, after a number of social media posts, blogs and newsletters noted the missing link in the Harlem Cultural Festival’s history, the filmmakers have begun to recognize Lauro’s role.

“There is no doubt of Joe Lauro’s previous involvement with the concert footage from the Harlem Cultural Festival,” a Searchlight representative said in a statement to The Times. “Hal Tulchin and others attempted to get this film made for many decades, but unfortunately never succeeded. The filmmakers of ‘Summer of Soul’ didn’t leave this history out of the film’s narrative to ignore their work with the concert footage. In fact, in recent interviews, the producers have acknowledged that anyone who recognized the value of the footage deserves credit for that.”

The response should give comfort to those who have devoted their careers to preserving pop culture history.

“If Joe had not done what he did on the Harlem Festival, it may have been eventually thrown out,” said David Peck, owner of the San Diego-based archive house Reelin’ in the Years Productions. “Sometimes tapes deteriorate beyond repair. Joe did the world a service, even if he’s not getting the fruits of that service.”

Lauro, who directed a 2014 film about New Orleans music legend Fats Domino, is now at work with Gordon on a documentary about the Newport Folk Festival, using 100 hours of archival footage from the mid-1960s. He does not expect the project to slip away.

“We own the footage,” Lauro said.

‘Summer of Soul’

Where: Hulu

When: Any time

Rating: PG-13 for some disturbing images, smoking and brief drug material.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.