Netflix to put a new spin on L.A.’s classic Egyptian Theatre

Like other movie houses in Los Angeles, the Egyptian Theatre remains closed indefinitely because of the conoravirus outbreak. But Rick Nicita, the chairman of the theater’s longtime owner American Cinematheque, says the future is bright.

Credit his optimism to, of all things, Netflix.

On Thursday, the Los Gatos, Calif., streaming giant said it had closed its long-in-the works deal to buy the Egyptian Theatre for an undisclosed sum from American Cinematheque, a Los Angeles nonprofit that has owned the venue since 1996.

After more than a year of negotiations with the organization and state and local officials, the acquisition marks the beginning of a new era for one of Los Angeles’ oldest cinema treasures.

“Love for film is inseparable from L.A.’s history and identity,” Mayor Eric Garcetti said. “We are working toward the day when audiences can return to theaters — and this extraordinary partnership will preserve an important piece of our cultural heritage that can be shared for years to come.”

On the surface, it’s an odd marriage. One is the world’s biggest video streaming service, representing the entertainment industry’s future. The other is a nearly century-old symbol of the bricks-and-mortar past, having held the 1922 premiere of “Robin Hood,” starring Douglas Fairbanks.

After the talks emerged in April 2019, some local cinephiles scratched their heads. Dues-paying members of American Cinematheque and filmmakers such as Michael Mann and Jon Favreau contacted the nonprofit to learn what the deal meant for the Egyptian. Would the sale compromise the theater’s mission to provide the greatest cinematic art on the big screen?

Netflix is poised to buy the historic Egyptian theater from the nonprofit American Cinematheque. Some local cinephiles are worried

Quite the contrary, said Nicita, 74. American Cinematheque will continue to program its screenings at the Egyptian on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays, by far its busiest days, while Netflix will use it to hold premieres and filmmaker events for its growing movie business on weekdays.

Netflix and American Cinematheque declined to disclose financial terms, but Nicita said the purchase will provide the organization with a much-needed influx of cash to fund a renovation of the venue and put on more of its signature programming, including filmmaker Q&As and film festivals. The nonprofit may even be able to fly in filmmakers for events, rather than trying to catch them while they happen to be in town.

“We get improved programming at a renovated theater,” he said. “Programming doesn’t suffer, the programming only gets better. The theater doesn’t suffer, the theater gets better.”

The closing of the deal, said to be worth tens of millions of dollars, including improvements, marks a significant milestone in Netflix’s efforts to become an increasingly powerful force in the film business.

Preserving and restoring the Egyptian is an opportunity for the company to make further inroads with established filmmakers and up-and-coming talent by giving them a high-profile venue to showcase their work, said Scott Stuber, head of Netflix Films. The company last year signed a lease to save New York’s Paris Theater, one of the city’s oldest art houses.

“It was kind of a perfect opportunity,” said Stuber, 51. “It gives us a chance to have a premiere venue where filmmakers and artists enjoy the experience.... It was a nice fit for everything we’re trying to achieve as a company.”

It remains unclear when Netflix will be able to start its renovations.

Los Angeles officials have yet to give theaters the go-ahead to reopen, and Stuber said the company is waiting for clear public health guidance before moving ahead to assess improvements. Commercial theater chains are hoping to be up and running by early July, nationwide. Some projects will probably include theater technology and seating, Stuber said.

“We’re going to wait until we’re given the green light,” said Stuber, who has fond memories of seeing movies including “Apocalypse Now” at the Egyptian. “We would need to go in with teams to figure out what needs to be done.”

Negotiations started roughly a year and a half ago, when Netflix Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos, who’s served on the American Cinematheque’s board for years, floated the idea with Nicita.

American Cinematheque, which also leases the Aero Theatre in Santa Monica, was struggling financially. Like many nonprofits, the organization, established in 1984, was cash-strapped and needed an influx of funds to make necessary repairs to the Egyptian and continue its mission.

“It was going to become essential,” Nicita said. “We were going to approach a crisis point in the not unforeseeable future.”

Sarandos recused himself from negotiations, Nicita said.

But the proposed deal still raised hackles among local preservationists who wanted more assurances that American Cinematheque would honor its commitment to the city to maintain the venue as a showcase for the best of cinematic art. The group bought the theater from the Los Angeles Community Redevelopment Agency for $1 in 1996 and pledged to restore it to its former status.

Some locals fretted about what would happen after the classic theater was handed from the American Cinematheque to a for-profit business.

Traditionalists in the film business have long held suspicions about Netflix because of its practice of releasing movies for streaming at, or near, the same time that they’re released in theaters. Los Angeles preservationists Richard Schave and Kim Cooper, who run a tour company, circulated a petition last year calling for greater transparency into the deal.

State and local officials also wanted assurances that the deal was in the best interests of the community. Although negotiations between Netflix and American Cinematheque were smooth, it took longer than expected to get the blessing of civic leaders, Nicita said.

“We were the ones under the microscope,” he said.

Officials eventually signed off. Los Angeles Councilman Mitch O’Farrell, who represents the 13th District, praised it as a win for “film, historic preservation and the arts.”

“The collaboration ensures the cultural destination remains in the heart of Hollywood for decades to come,” O’Farrell said in a statement.

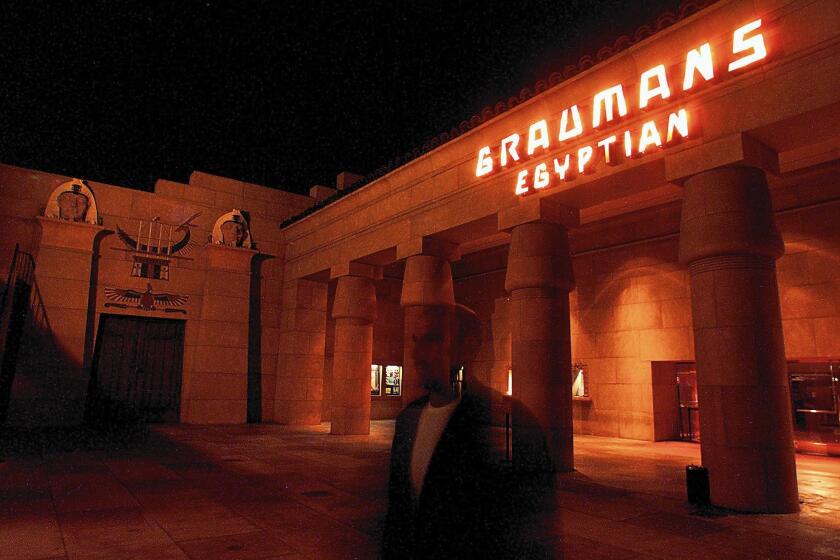

The Egyptian Theatre has survived multiple ownership changes since it opened nearly a century ago. Sid Grauman built the theater five years before the opening of his more famous Chinese Theatre nearby. Besides “Robin Hood,” the Egyptian also held the premiere of Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 silent film “The Ten Commandments.”

The theater closed in 1992, having fallen from its former glory under the ownership of United Artists Theatres. The Los Angeles Community Redevelopment Agency bought the theater and the property for $1.7 million, as part of its mission to revitalize the surrounding area.

After American Cinematheque took over, the venue, which suffered damage in the 1994 Northridge earthquake, underwent a $15-million renovation with the help of a CRA grant, and reopened in 1998. The former 1,100-seat theater now houses a 616-seat auditorium and a 78-seat screening room named for Steven Spielberg.

Netflix is enjoying a surge in online viewing because of people sequestered at home with few entertainment options during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For theaters, the pandemic could portend a more treacherous future as moviegoers weigh when to return to the cinema. Even traditional movie studios, such as Universal Pictures and Warner Bros., are making more films that will be viewed primarily online.

However, Nicita and Stuber both dismissed the notion that Americans may not return to theaters in large numbers.

“I have no doubts about the theatrical experience,” Nicita said. “As soon as we can pack a house, I believe it will be packed.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.