One year after Moonves’ exit, CBS TV stations also face harassment and misogyny claims

Jill Arrington was a star in TV sports. Then, four years ago, the former NFL sideline reporter traded national exposure for what she thought would be a more stable job at CBS’ television stations in Los Angeles.

Arrington loved chronicling the Rams and other pro teams, and eventually took on additional duties as the weekend sports anchor for KCBS-TV Channel 2 and KCAL-TV Channel 9. But one thing about her job galled her: She was earning nearly $60,000 less a year than the male anchor she replaced.

When her contract came up for renewal, Arrington told the station’s top managers that it was unacceptable to pay a woman so much less than a man.

“Oooh, isn’t she tough,” Arrington recalls the former general manager of CBS’ L.A. stations, Steve Mauldin, saying during a March 2018 meeting. She said Mauldin turned to his lieutenant and said: “This one talks more than my wife.”

The meeting ended with no assurance of a raise. But as Arrington started to leave, she said her boss told her: “Put on a tennis dress and meet me at the golf club. We’ll put you on tape, and you can make some extra money.”

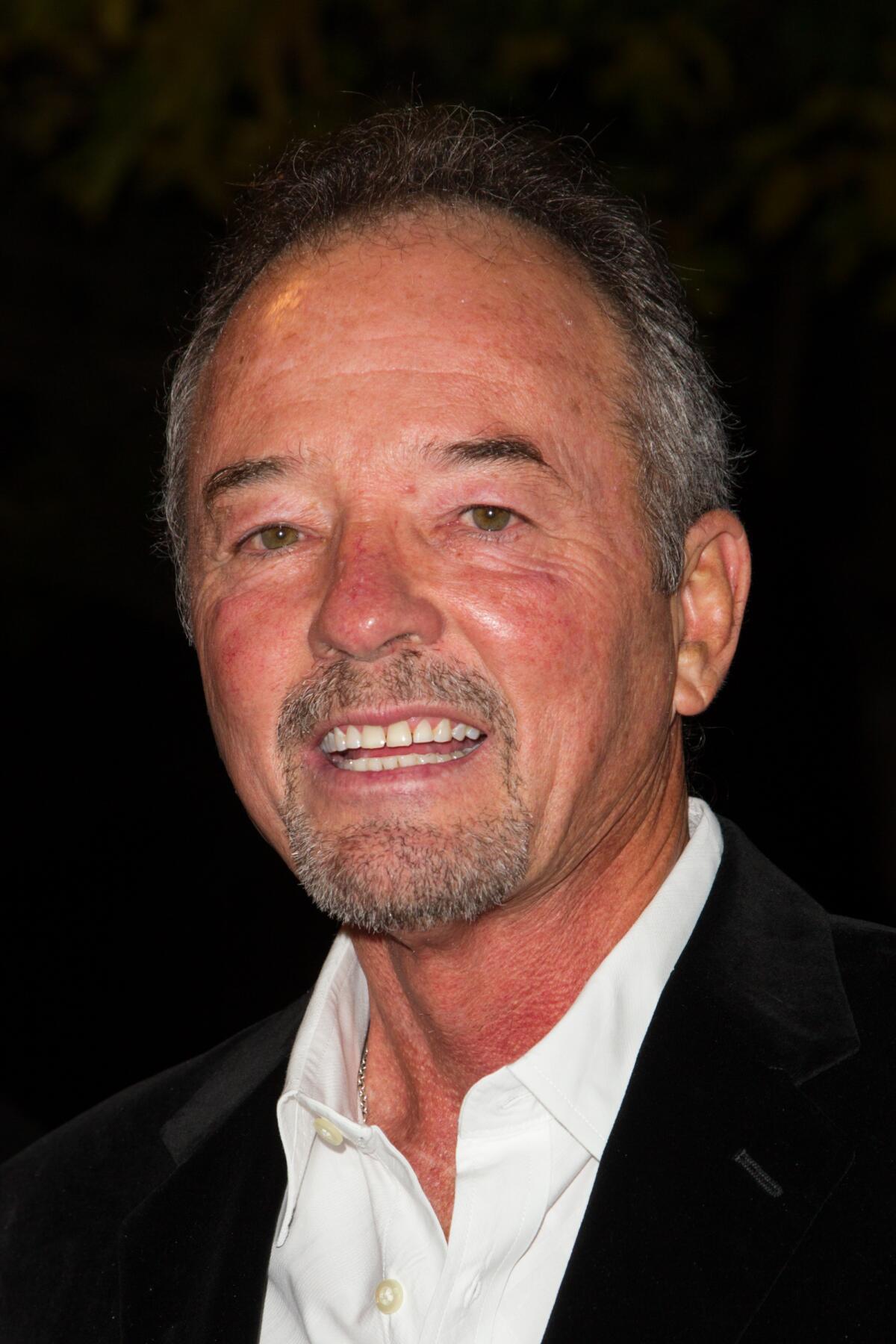

Leslie Moonves was a television great.

Arrington had experienced come-ons in her years covering sports, but nothing like this. She confided in a colleague, who recalled that Arrington was “frantic and scared” after the exchange. In an interview last week, Mauldin denied making the remarks. “That didn’t happen,” he said. “That’s the most absurd thing. I would not talk to women that way.”

Six months after that meeting, a bombshell detonated at the highest level of the company: CBS’ larger-than-life chief executive, Leslie Moonves, was ousted over claims he harassed and assaulted multiple women decades ago.

After a high-profile probe into Moonves’ conduct and the company’s workplace culture, independent law firms hired by CBS concluded that “harassment and retaliation are not pervasive at CBS.” But a Times investigation has uncovered claims of discrimination, retaliation and other forms of mistreatment in an overlooked but significant corner of the company: the chain of CBS-owned television stations.

More than two dozen current and former employees of KCBS and KCAL described a toxic environment where, they said, employees encountered age discrimination, misogyny, and sexual harassment — and retaliation if they complained.

Discrimination complaints have also surfaced at CBS-owned stations in Chicago, Dallas and Miami. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission filed a lawsuit against CBS after investigating allegations that station managers in Dallas denied a full-time position to a 42-year-old traffic reporter and instead hired a 24-year-old former NFL cheerleader who didn’t meet the job’s requirements. CBS denied that it engaged in discrimination.

In late November, shortly before a scheduled trial, CBS reached a tentative agreement to resolve an age discrimination and retaliation lawsuit brought by award-winning Miami-based journalist Michele Gillen, who sued CBS last year. The company admitted no liability in the agreement. In her court filings, Gillen called CBS a “good ole boys club” that “protects men despite bad behavior.”

Managing a nationwide television station group with thousands of employees is challenging, CBS Television Stations President Peter Dunn said in a statement. But, he added, “the vast majority enjoy where they work every day and take great pride in serving their local community. At the same time, I am very mindful that in a large company we have people who are unhappy at times. We respect all voices who express workplace concerns to us.”

The job has become even more challenging due to profound shifts in media. TV stations are no longer the profit centers they used to be. At some stations, including KCBS and KCAL, anchors have seen their salaries shaved to save money. Highly paid employees are booted, and station managers increasingly rely on part-time workers to deliver the news. But networks still haven’t attracted younger audiences.

“Like all local stations, we are competing for viewers in an evolving media world,” Dunn said. “This evolution has created natural tension with some employees and external constituents.”

Transforming the TV station business, which remains rooted in old-school economics and attitudes, is a key challenge for the newly created ViacomCBS Inc. media company. In many ways, TV stations are stuck in a bygone era where women are judged by their appearance, and subjected to overt and subtle discrimination. Skin-tight dresses remain the norm. Older workers watch as coveted assignments go to younger reporters as stations try to appeal to younger viewers.

CBS is not the only broadcaster struggling with business shifts and complaints of ageism. L.A. station KTLA-TV Channel 5, formerly owned by Tribune Media, as well as the cable giant Charter Communications and the Sinclair Broadcast Group have all faced discrimination claims.

But CBS has a history of complaints, particularly in its treatment of women. In 2000, the company paid $8 million to settle a lawsuit brought by the EEOC, the government agency that polices workplace law compliance. The agency found that women at seven CBS TV stations, including KCBS, endured a hostile work environment that included sexual harassment and retaliation for complaining. About 200 female technicians at CBS stations — camera operators and engineers — were paid less than men and passed over for promotions, the EEOC found.

Michele Gillen was a reporter for CBS’ WFOR-TV Channel 4 in Miami. She sued her former employer, alleging age and sex discrimination.

Today, the two CBS stations in Los Angeles produce 78 hours of newscasts each week, making it one of the city’s busiest local TV news operations. More than 120 people work at the two stations’ newsroom, which is wedged into CBS Studio Center, a busy TV production hub in Studio City where TV shows such as “Brooklyn Nine-Nine” and “Why Women Kill” are shot. Moonves maintained a stately office on the lot, a short distance from the stations’ broadcast center, which sits a few yards from the site of the lagoon in “Gilligan’s Island.”

Known as “CBS L.A.,” the stations share management and a ground-floor newsroom. They are part of the chain of 28 stations owned by CBS.

In each market, a general manager handles day-to-day operations but oversight of the group rests in New York. For the last decade, Dunn and David Friend, two executives in New York, have managed the group.

“CBS-owned stations get very little leeway in anything — it’s just the corporate mind-set,” said one veteran producer who was not authorized to comment.

The L.A. stations were managed by Mauldin until last June, when he retired at age 70 after 40 years in the TV station business. He was friendly with Moonves, according to two people with the matter. Mauldin had previously been GM of CBS’ stations in Dallas and Miami.

During the last seven years, multiple women at the Los Angeles stations complained that they were subject to harassment by their bosses or colleagues.

Early in 2018, prominent KCAL anchor Leyna Nguyen complained to KCBS management about inappropriate comments and unwanted touching by a male colleague, according to several people familiar with the matter. CBS spent months investigating the allegations but concluded there was insufficient evidence of wrongdoing, according to a person familiar with the situation who was not authorized to comment publicly and requested anonymity.

CBS reached a settlement with Nguyen in July 2018 — just days before the allegations about Moonves became big news. Nguyen, a 20-year employee who left KCBS following the incident, declined to comment on the matter. CBS also struck a separation agreement with the person who was accused of the misconduct, and he also left. CBS did not admit liability in the matter. The employee denied wrongdoing and did not respond to a request for comment placed through his attorney.

The station’s then-head of makeup, Gwendolyn Gatti, backed Nguyen’s allegations. Gatti said the same employee harassed her, too, and that he “propositioned her for sex, asked about her sex life,” “slapped her on the buttocks,” and used the N-word when referring to her, according to a lawsuit in a separate case. CBS settled the matter with Gatti on July 27, 2018, according to court records. In a court filing, a CBS attorney labeled Gatti’s sexual harassment allegations “frivolous.” CBS denied any liability, according to a partially redacted copy of Gatti’s settlement agreement.

A former KCBS employee told The Times that he recalled a separate episode several years ago when Gatti was near tears and shaking with anger after a different colleague, a cameraman, forcefully slapped her on the buttocks. A second person confirmed that CBS investigated the slapping incident and the cameraman was disciplined.

Gatti was fired in September 2018, two months after her settlement. The 64-year-old makeup artist sued CBS in Los Angeles Superior Court in February, alleging wrongful termination, discrimination and retaliation. CBS, in court documents, said Gatti was fired “after she brought illegal drugs onto CBS property, in violation of company policy.”

In her lawsuit, Gatti said she realized her wallet was missing on Sept. 18, 2018, and called CBS’ security office to see if it had been turned it in. Later that day, she said she was called to the security office and presented with what she said were two empty plastic bags that a security guard claimed were found in her wallet. Gatti denied the bags were hers and “stated that she does not use any illegal drugs,” according to the lawsuit. She was fired the next day.

Nguyen and Gatti complained to management about sexual harassment in March 2018, according to court records. This was the same month that Arrington, the weekend sports anchor, began inquiring about her contract renewal. A single mom, she had been at the station more than two years, her duties had increased, and she wanted a raise.

The Times independently confirmed that CBS was paying Arrington about $60,000 a year less than her male predecessor. Arrington said her goal simply was to extend her contract, which expired in April 2018, and get a bump in pay to an anchor’s salary because she was putting in long hours serving as both a reporter and an anchor — appearing in as many as seven telecasts on a weekend shift.

Arrington was far from the highest-paid employee at the station, according to a person familiar with KCBS’ finances. Her salary put her among the middle of the pack. She was told to discuss the situation with Mauldin, which led to the awkward exchange.

Arrington’s colleague, Elsa Ramon, a former KCBS and KCAL anchor, confirmed that Arrington shared details about the incident with her shortly after it occurred in early 2018.

“She was uncomfortable,” Ramon said. “Mauldin made a suggestion that she engage in some activity,” adding that she viewed it as a quid pro quo situation.

A second CBS executive who attended the meeting said he didn’t recall Mauldin making inappropriate comments. Arrington claims that executive left the meeting just before she did. The second executive and Mauldin said they felt that Arrington was out of line in asking for a substantial raise over her $135,000 annual salary at a time when the station was struggling to control costs. (Arrington said she made no specific salary demands, and merely asked to be paid what other anchors in L.A. were making.)

“I thought she was making a good salary,” Mauldin said. “She thought she was worth more.”

Arrington initially was reluctant to talk to The Times.

Before joining KCBS, the 47-year-old Georgia native worked at Fox Sports, ESPN and CBS Sports, where she was seen by millions of viewers on the sidelines of NFL games and hosting shows about college football and NASCAR. Playboy readers in a 2000 online poll voted her America’s “sexiest sportscaster.” She declined the $1-million offer to pose for the magazine.

She arrived at KCBS and KCAL in 2015 after being recruited by Bill Dallman, a popular station news director who was also a Fox Sports alum. Arrington said she accepted the CBS stations job even though it meant lower pay and less exposure than a position at a national network. She was then in her 40s and working in on-air roles, a corner of the industry that can be unforgiving to women as they age.

Arrington nonetheless said she “felt it could be a whole new career for me, and a place where I could work for the next 10 years.”

Dallman, who now is news director for an ABC affiliate in Seattle, told The Times: “Jill and I both worked diligently to improve the quality of the on-air product and the culture in the building.”

Arrington enjoyed her experience early on, particularly co-anchoring KCAL’s weekend “Sports Central” with Gary Miller, an ESPN veteran. Miller, who now works at a Cincinnati station owned by Sinclair, said in an interview that Arrington was capable and a team player. Another KCBS reporter said: “She was one of the best we’ve ever had.”

Miller said Arrington confided in him that she was uncomfortable with Mauldin’s comments. Miller said he encouraged Arrington to complain to the human relations department, but she felt her best option was to avoid Mauldin. “He would start talking about her appearance or ask about her private life,” Miller said. “It was so inappropriate.” Mauldin denied the claims, saying “there was never a time when I put her in an uncomfortable position.”

Miller was let go in January 2017 due to budget cuts, and Arrington’s workload increased.

There were other tensions, too, according to seven current and former station employees interviewed by The Times. Jim Hill, a former NFL player and a fixture in L.A. broadcasting, was the station’s main sports personality and its sports director. He seemed uninterested in sharing the limelight, these people said.

“Jim wanted to handle the big stuff,” Mauldin said, adding that Hill was one of his favorites. “He wanted to do the big interviews, and I think Jill had a problem with that. ... I don’t think people down there [in sports] were comfortable being around her because of where her head was at.”

Arrington’s feature stories rarely appeared in Hill’s shows, she and others familiar with the situation said. Even a powerful report on an NFL lineman battling depression didn’t make the cut. Instead, the station ran preseason baseball clips.

“She wasn’t allowed to do stories that she wanted to do,” Miller said.

Hill did not respond to a request for comment.

Arrington said she tried to persevere: “I was just hoping the quality of my work would speak for itself.”

In early August 2018, the high-profile investigation into CBS’ culture began. Arrington’s attorney, Bobby Hacker, said he reached out to lawyers conducting the review because of concerns about Arrington’s treatment. But Arrington didn’t get a chance to talk to the investigators.

She was blindsided a week later on Aug. 22, 2018. It was her first day back at work after spending the weekend covering a Rams-Oakland Raiders preseason game. She was summoned to a conference room, where Tara Finestone, the news director who had replaced Dallman in January 2018, told her it was her last day.

Arrington demanded an explanation. She recalls Finestone saying: “We’re not firing you. We are happy with the quality of your work.” Instead, Arrington was told her position was no longer being staffed.

“I thanked her for her contributions and we talked about budgetary reasons,” Finestone told The Times. “Hers was the position that we decided to eliminate.”

More than a year later, Arrington still hasn’t landed a new job and she fears for her future.

“My takeaway from my experience at KCBS is that they were more concerned with protecting political alignments rather than the quality of their on-air broadcasts,” she said.

Colleagues and others also were confused by her abrupt departure. “My dealings with Jill were always first rate,” said Steve Brener, Dodgers spokesman. “She was professional and easy to work with. Then one day, she wasn’t here any more.”

Other station staffers say management decisions can be capricious and punitive. In 2013, Emmy Award-winning KCBS reporter Joy Benedict, who had just become the union shop steward at the station, posted a photo on Facebook of herself playfully posing on a giant chess board while on vacation in Miami with the caption, “Who wants to play with me???” Executives in New York became upset when a TV industry blog reposted the picture. They ordered KCBS managers to fire Benedict over the picture, according to three people with knowledge of the incident. KCBS executives felt that was too harsh of a punishment but they nonetheless assigned Benedict to primarily work less desirable weekend shifts. CBS representatives pointed out that she has since been given additional on-air opportunities at KCBS and CBS News.

Nancy London, who worked at CBS for 34 years, found herself on the outs after years of favorable performance reviews.

Nearly a decade ago, London, who worked at KCBS in technical services, received a new assignment and a new boss. He “harassed and ridiculed” her, she claimed in a lawsuit, alleging age, race and sex discrimination. London is African American. When she complained to HR, she said the situation grew worse. In July 2011, she was confronted by her boss and three other men who “railed upon” her in a group setting, London alleged in court filings. She fainted, requiring medical attention, according to the lawsuit.

A week later, London was fired.

London sued CBS in 2012, alleging wrongful termination. CBS dismissed London’s account as baseless. CBS settled the case in 2013 and did not admit liability. London declined to comment.

Several older CBS workers in L.A. also have alleged that they have been subject to age discrimination. The company also has come under criticism for its use of so-called per diem reporters, some of whom have worked for CBS for decades. These employees refer to themselves as freelancers, but some have been there so long that they jokingly call themselves “perma-lancers.”

Los Angeles relies heavily on per diem talent, according to executives and agents. The system causes resentment because it results in two classes of staff members working side by side. Using more per diem, part-time workers allows the stations to save money on personnel costs.

“People want to work in L.A., so there is a bigger pool of talent,” said one veteran CBS executive. “It comes down to market conditions.”

In the last 18 months, the station hired several new part-time reporters in their 20s. Younger reporters tend to get marquee weekday slots, which has caused resentment among some veterans, according to interviews and a review of KCBS staffing schedules.

In the just-completed November sweeps, KCBS and KCAL tied for sixth place in Los Angeles in viewership to late local newscasts. Market leaders are Walt Disney Co.’s KABC-TV Channel 7 and Univision’s KMEX-TV Channel 34.

“They are trying to cut, cut, cut and it’s taking a toll,” said Ramon, the former anchor who left the station in spring 2018. Ramon, 48, left rather than return to the weekend shift after spending two years filling in on prominent weekday newscasts because she cherished that time with her kids. She said she did not experience sexual harassment, but she didn’t see any opportunity for advancement, particularly because the station was investing in younger workers. “I felt that I was just spinning my wheels,” she said.

Numerous people said the atmosphere at KCBS and KCAL deteriorated after Dallman left.

Six employees told the Times that what they perceived as a hostile atmosphere at the station contributed to their decision to leave it in recent years.

Earlier this year, KCBS employees brought their concerns about stagnant wages and reliance on long-term freelancers to their union, SAG-AFTRA. Nearly two dozen reporters and anchors signed a petition in May. A union representative declined to comment on pending negotiations.

Mauldin denied that women were treated poorly or underpaid and said that the highest-paid talent was 30-year anchor Pat Harvey, a woman.

“We didn’t pay women less than men because they were women,” he said. “We respect everyone. But when you cut back in business, it’s difficult on people.”

CBS has faced workplace complaints in other divisions. Scott Pelley, 62, the respected former anchor of the “CBS Evening News,” told CNN that he lost his job as chief anchor “because I wouldn’t stop complaining ... about the hostile work environment.” CBS also ousted two big names — morning news anchor Charlie Rose and former “60 Minutes” executive producer Jeff Fager — over allegations of inappropriate conduct.

CBS’ board a year ago acknowledged shortcomings. “Historical policies [and] practices ... have not reflected a high institutional priority on preventing harassment and retaliation,” the board said of the investigators’ findings.

At KCBS and KCAL, a new general manager, Jay Howell, arrived in July, after spending the previous year running CBS stations in Pittsburgh.

Some staff members said they doubt reforms will filter down to the local stations.

“I don’t think they care about us,” said one insider, who did not want to be identified out of fear of being punished.

Times staff writer Stacy Perman and staff researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.