Hollywood is changing fast. The people running it are not

This is the June 7, 2022, edition of the Wide Shot newsletter about the business of entertainment. If this was forwarded to you, sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Last week’s shakeup at Warner Bros. Pictures in Burbank prompted the usual metaphors involving musical chairs (including in my write-up) to describe the ongoing cycle of familiar faces atop the Hollywood studios.

Indeed, during the last few years, executive intrigue at the major studios has been best characterized by a sense of monotony, with familiar names always popping up for whatever big jobs become available. The more the film industry changes, the more the people running it stay the same.

The prime example is Michael De Luca’s ascension to the top of Warner Bros. Pictures. Or sort of the top. He and his former MGM partner Pamela Abdy will serve as co-chairpersons of the studio, but the job formerly held by Toby Emmerich will eventually be split into three divisions reporting to Warner Bros. Discovery Chief Executive David Zaslav. Separate executives to-be-determined will shepherd the DC superhero films and Warner Bros. Feature Animation.

Those caveats aside, it’s the ultimate full-circle move for De Luca, who as a young up-and-coming executive ran production for New Line Cinema under Bob Shaye and Michael Lynne until his ouster in 2001 when he was replaced by Emmerich. De Luca and Abdy will now oversee both Warner Bros. and the New Line label. And round and round they go.

This is an extreme version of a common quirk of the movie business, where the names put forth for the top studio roles have long been the same people who ran the dream factory one or two decades ago. The New York Times described the shuffle as the latest continuation of a “longtime game of rearranging executive deck chairs,” only leaving out the phrase “on the Titanic.”

Tom Rothman, who once presided over Fox Filmed Entertainment for more than a decade, has led Sony Pictures’ film group since replacing Amy Pascal in 2015. His fellow Fox co-chair Jim Gianopulos guided Paramount Pictures until being replaced by Nickelodeon’s Brian Robbins last year, representing a chink in the old guard’s armor. Alan Horn only just left Walt Disney Studios at the end of last year. Horn’s exit followed a distinguished run at the Mouse House, itself a late-career act after he was pushed out of Warner Bros for, ironically in retrospect, being too old-fashioned.

The business has been ripe for a broader generational changeover as the world of entertainment warps around the gravitational pull of streaming and the technology giants. We’ll see how that takes shape.

Zaslav still has to pick someone to run the DC universe, which will be a key perch within the newly combined company, though that person will inevitably suffer comparisons to Marvel Studios’ Kevin Feige. Amazon’s Prime Video head Mike Hopkins is considering new film leadership for MGM. Among the names always mentioned for such roles in various rounds of speculation is Emma Watts, a former Fox and Paramount film executive.

The repetition has started to abate somewhat, with the inclusion of less obvious-seeming choices.

Robbins comes from the world of kids television from his child acting role in “Head of the Class” to running Awesomeness TV and Nickelodeon. Abdy, the incoming Warner Bros. Pictures co-chair, has cut her teeth in the business of quasi-independent commercial movies, leading production at Arnon Milchan’s New Regency before producing movies like “Queen & Slim” as a partner with Brad Weston at Makeready and later joining MGM.

Still, a veteran media executive recently bemoaned to me the lack of a new generation of young hotshots to take the studio mantle, a frequent complaint in the often staid film business. There are several competing and not-mutually-exclusive theories for the slow churn.

- First, young would-be studio heads would rather run tech companies. An ambitious and smart aspiring businessperson looking to make a name for oneself might think twice before going into an industry that so many people think is in a state of managed decline. They might want to get into a growth industry instead. And for those seeking the stable, yuppie suit-and-tie lifestyle, law school might be a better bet than the talent agencies and entertainment companies at this point.

- There’s not much of a clear farm system for developing new talent. That role used to be filled by companies like New Line, where not only De Luca and Emmerich but also current Universal Pictures chief Donna Langley made their marks. De Luca and Emmerich were 30-somethings during their first do-si-do. Today’s business has few shingles, if any, like the old New Line, which bridged a gap between independent and mainstream commercial cinema. The ones that do, like A24, are more powerful as independents and are totally different from the franchise-obsessed, conglomerate-owned studios. Those who run businesses with more autonomy and lucrative deals, like Legendary film head and “Dune” producer Mary Parent, tend to like it that way.

- Businesses in flux often want a “steady hand” to steer the ship. That often means going with someone who’s done it before. At Disney, Bob Iger needed a respected veteran like Alan Horn to serve as head-of-state at its studio business after flops like “John Carter.” He wanted someone with the gravitas to manage the increasingly unwieldly empire of Marvel, Pixar, Disney Animation, live action, Lucasfilm and the Fox assets. In Horn’s case, it worked. With the whole industry in flux, the tried and true bet sometimes looks attractive, even when an innovator would be the more forward-thinking choice.

- Despite the turmoil, these are high-profile, well-paid jobs. Studio chiefs tend not to surrender these roles willingly. Despite the total corporatization of the studios, there’s still some veneer of glamour to them. When people do step down, it’s often for a lucrative production deal with their former employer, like Emmerich’s new pact with Warner Bros. Discovery, which lasts for five years and covers movies and TV shows. It’s also a clubby business, where decisions are made based on established relationships.

All this to say that people in the film business love to stick with what works, especially in times of change. In a world in which 59-year-old Tom Cruise is still the world’s biggest movie star, and arguably bigger than ever, that shouldn’t be very surprising.

Stuff we wrote

— Counterintuitive? Perhaps. Netflix is cutting back, but not on L.A. productions, Wendy Lee reports. Despite recent layoffs, Netflix said it is doubling down on Los Angeles, filming at least 70 productions in the area this year as the streamer spends roughly $18 billion on content globally.

— 50 years after the Watergate break-in, John Dean relives the scandal that changed his life. The former Nixon White House counsel has become a go-to talking head on government corruption. A CNN documentary is his first on-camera look back at the event that resonates today, writes Stephen Battaglio.

— MoviePass died. But this movie theater subscription service hit a milestone. My conversation with Cinemark CEO Sean Gamble on the success of the company’s Movie Club program and the state of theatrical film.

— We can’t agree on the meaning of Depp versus Heard. Here’s how we move forward anyway. Mary McNamara and Meredith Blake debate takeaways from the celebrity defamation trial of the century

Number of the week

The typical blockbuster declines about 55% in its second weekend at the box office, compared with its three-day debut. The drop-off is often greater for movies that open with big sales. That’s called a “front-loaded” box office run. Right now, we’re seeing something unusual.

“Top Gun: Maverick” pulled off an extraordinary feat, grossing $90 million in weekend No. 2 for a mere 29% drop, the smallest second-week decline ever for a film that launched with more than $100 million in ticket sales. Yes, the lack of serious competition has something to do with the movie’s staying power, but the bigger factor is word-of-mouth praise.

What does this mean for the business of theatrical movies? The fate of the summer’s would-be blockbusters, including “Jurassic World: Dominion” and “Lightyear,” remains to be seen. It’s possible that “Top Gun: Maverick,” with its stellar reviews and audience reception, is an outlier rather than part of a trend.

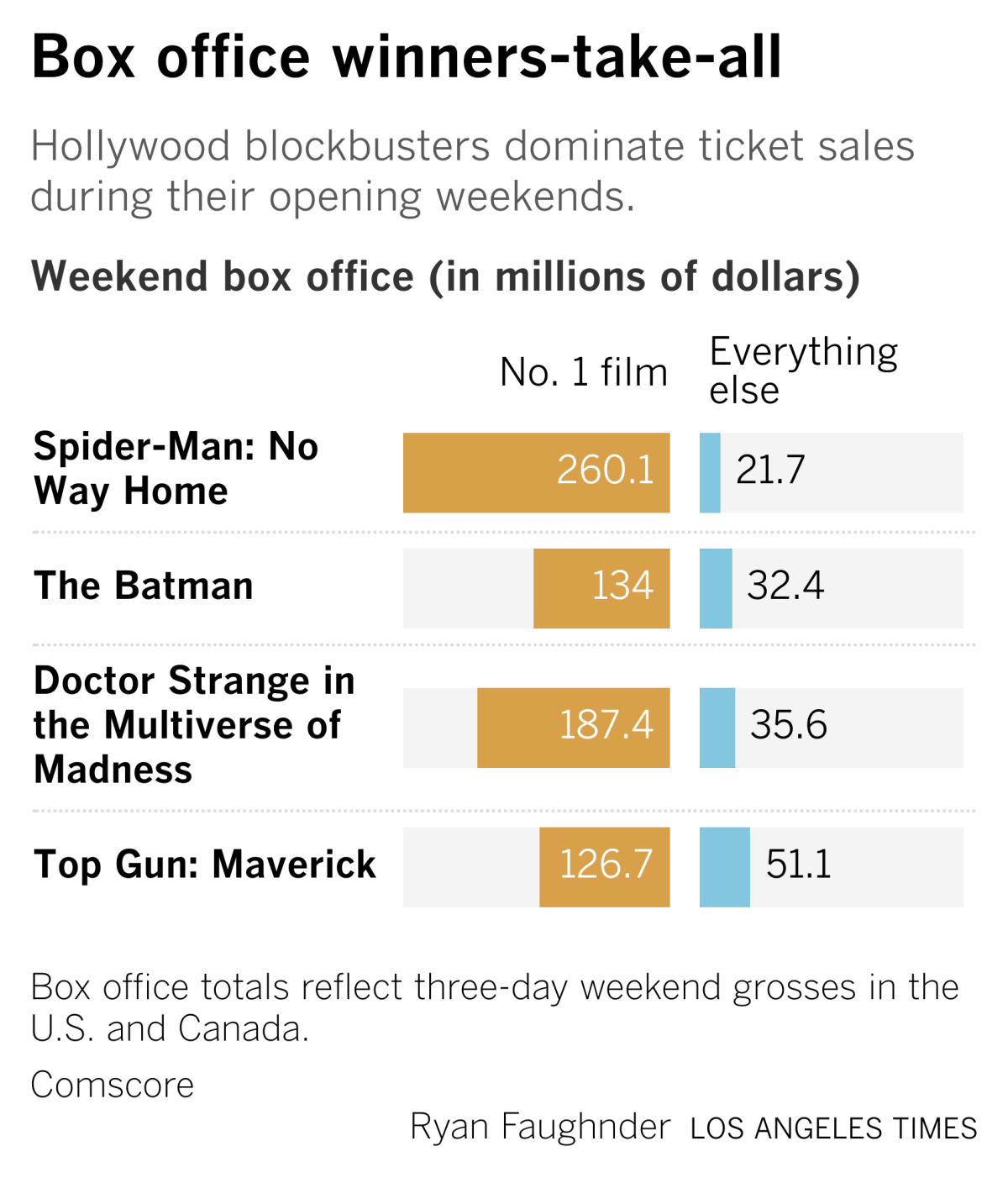

Exhibitors are ecstatic, of course. But there’s an extreme divide between the haves and have nots at the box office, where the winners-take-all dynamic is more pronounced than ever. The market share taken by the weekly No. 1 films, calculated on a trailing 52-week basis, crossed 50% for the first time, according to a report last week from Cowen & Co.’s Doug Creutz.

Quoteable

“We are in a golden age of content production and the dark age of creative profit sharing” — media investor Jeff Sagansky, speaking at the NATPE conference. (Deadline)

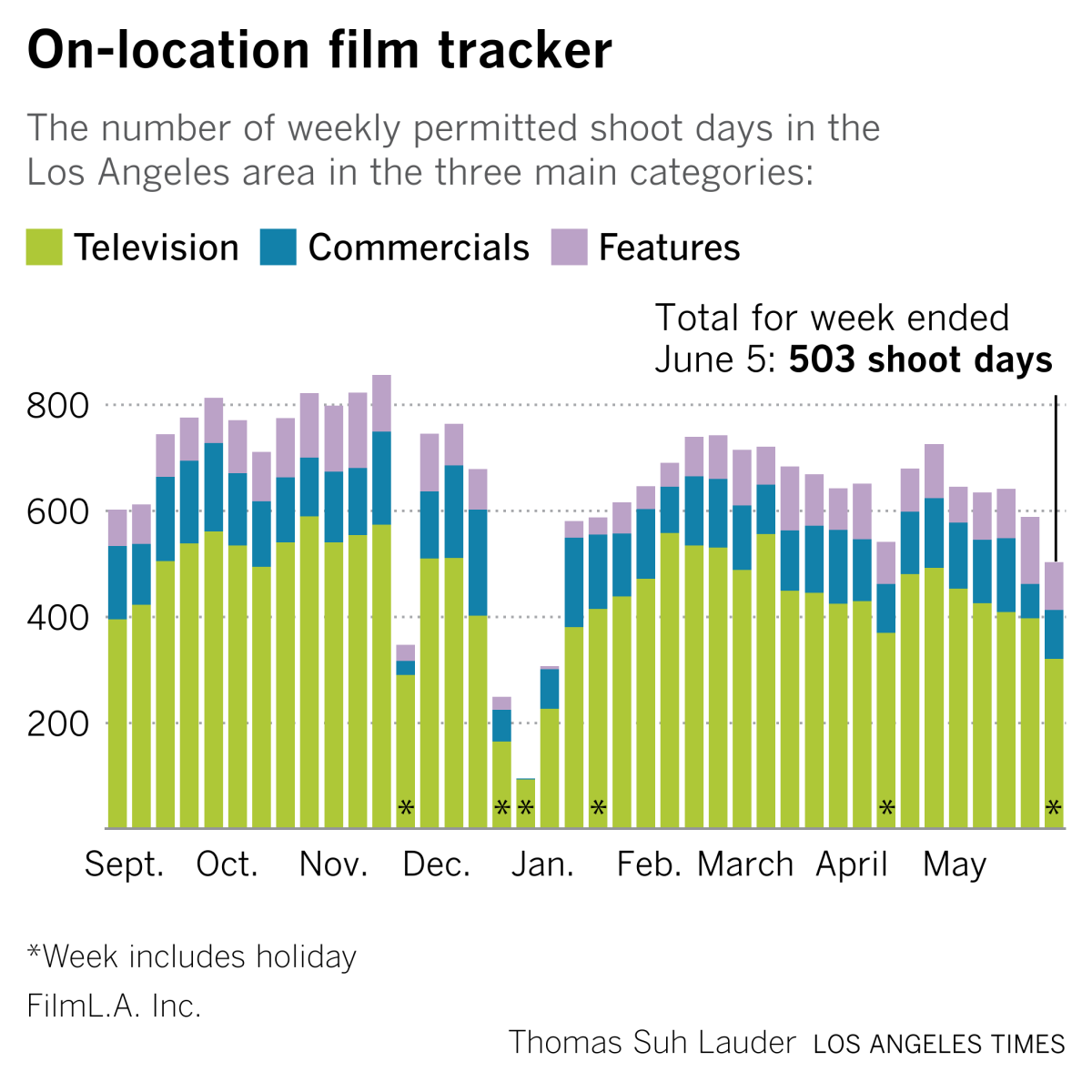

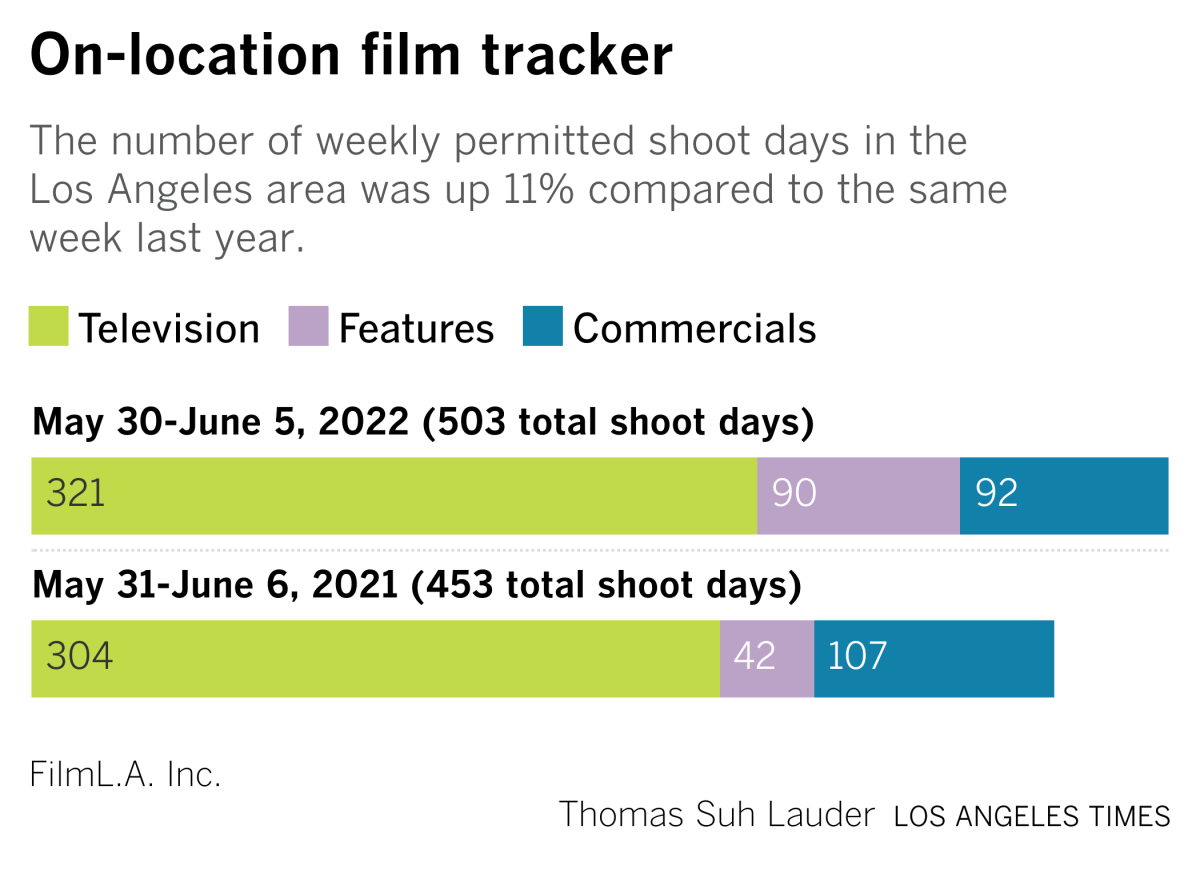

Hollywood production

On-location shoot days declined locally last week due to a drop in television production, according to data from FilmLA, but were still up 11% from the same period of time last year.

You should be reading...

— Tripp Mickle and Brian X. Chen on Apple’s next big thing, Jon Favreau and “products that blend the physical and virtual worlds.” (New York Times)

— Jimena Ledgard and Andrew Deck on Netflix’s messy password-sharing crackdown. (Rest of World)

— Wall Street Journal’s deep dive on Sheryl Sandberg’s Facebook exit.

— E. Alex Jung on the rise of comedian and “Fire Island” lead Joel Kim Booster. (Vulture)

Finally ... who framed IP?

“Chip ‘n’ Dale: Rescue Rangers,” streaming on Disney+, is not quite the contemporary equivalent of Robert Zemeckis’ landmark live action-animation hybrid “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?”

But it is a surprisingly sharp journey through the entertainment business’ obsession with established intellectual property, directed by Akiva Schaffer of the Lonely Island comedy troupe. It’s also a guide to the ever expanding variety of animation styles and an ode to the weird quirks of online pop culture. All hail Ugly Sonic!

The reality is, this release gave me an excuse to revisit the Lonely Island’s 2016 farce “Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping,” one of the best pure comedies of the last decade, despite being a box office bomb.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.