Animation by Tomasz Czajka / For The Times

After being found guilty on 34 counts of falsifying business records in New York this May, former President Trump declared that what had happened to him was a “disgrace” — choosing a word that conveys the utmost disgust and outrage. Fraught and weighty, the term leaves a stain. It’s also the title of the South African author J.M. Coetzee’s eighth and perhaps most significant novel.

My most lasting memory of “Disgrace,” published on July 1, 1999, is its stark and relentless brutality. The plot is explosive to the point of implausibility, and since the mind can only hold onto so many awful incidents at once, it can be hard to recollect the novel’s many acts of violation and rupture. What lingers is a wound that won’t heal; Coetzee wants the reader to dwell in the aftermath of horror. But “Disgrace” has lasted long enough to connect with a reader immersed in the similarly profuse horrors of the contemporary news cycle because of his ability to reach beyond the moment of trauma. He not only asks the reader to live with moral uncertainty and the discomfort of violent change, but also to accept that trauma is an ongoing state.

The 1999 Project

All year we’ll be marking the 25th anniversary of pop culture milestones that remade the world as we knew it then and created the world we live in now. Welcome to The 1999 Project, from the Los Angeles Times.

Writing in the aftermath of South African apartheid, Coetzee could have penned a sprawling epic. Instead, against the backdrop of Nelson Mandela’s ascension to political power as president of the African National Congress (ANC), and the 1996 establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to help his countrymen grapple with the past, the author operates with utmost restraint. Rife with unspeakable violence and shocking impasses, every word of the book’s 220 pages is measured and necessary. There’s no filler or gloss.

The reader walks in intimate step with 52-year-old David Lurie, a twice-divorced literature and language professor living in Cape Town. The novel’s first rupture, nearly two decades before the reckoning of #MeToo, is his expulsion from the academy after a sexual relationship with a student — the transgression that readers tend to remember. And yet, though Coetzee captures the changing tide of propriety and sexual politics with this ugly interlude, it’s merely the first in a series of cascading traumas. In “Disgrace,” gender politics, nationalism, racism, sexual violence and the steep challenge of reconciliation through community building are all on the table.

David, finding himself unemployed and alienated thanks to his actions, retreats to South Africa’s Eastern Cape to lick his wounds. He arrives at his adult daughter Lucy’s farm where she labors alongside Petrus, a Black South African with a land grant. Unrepentantly grousing to Lucy that “These are puritanical times. Private life is public business,” disappointed by her rural existence, unsophisticated appearance and unspoken lesbianism, David nonetheless tries to make the most of his exile. He muddles along with a book project on Lord Byron’s later years, specifically his mistress in Italy, and lends a hand to the local animal welfare shelter, overrun by dogs without homes. You might even expect the novel to depict David discovering harmony, personal and pastoral, in this new environment.

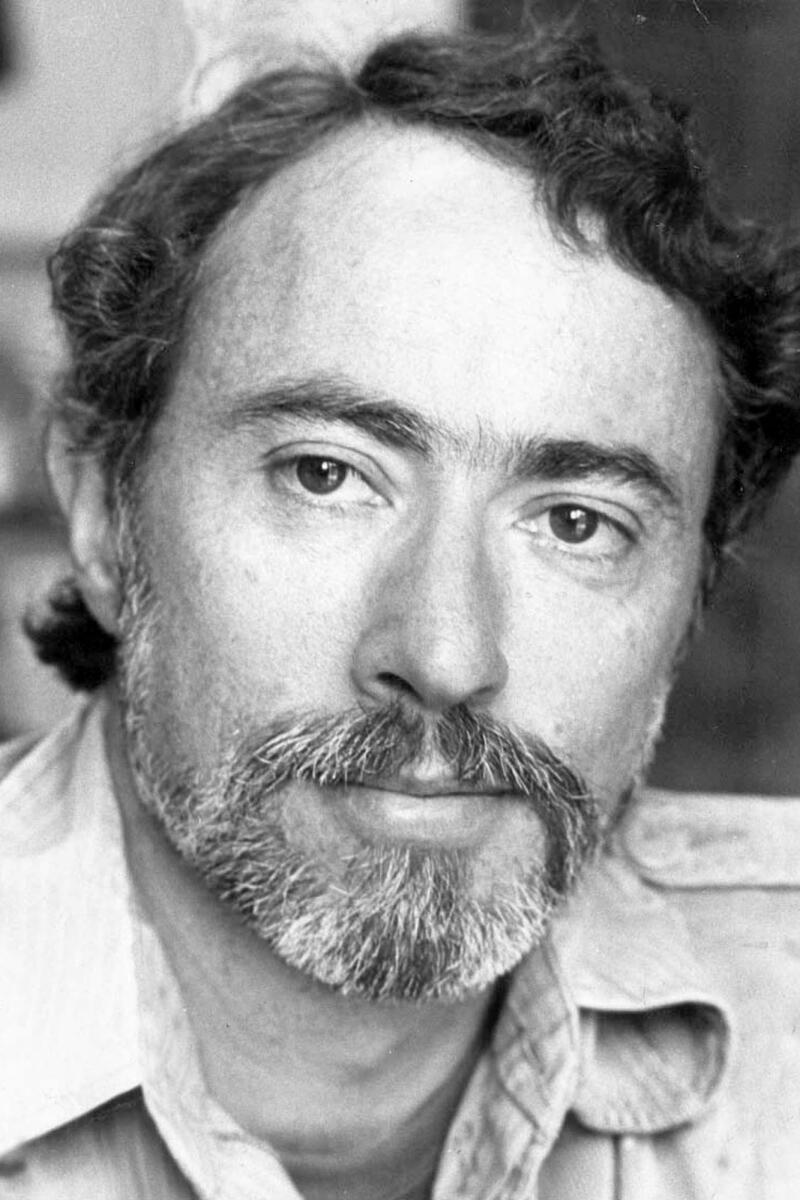

South African writer J.M. Coetzee. (Associated Press) (Michael Stephens / PA Images via Getty Images)

Instead, an act of violence shatters the precarious peace. With Petrus elsewhere, three men and a teenage boy arrive at Lucy’s door, loot the house, kill all but one of her dogs, attempt to set David on fire and then gang rape her. Confronted by her father about why she’s not pressing charges regarding her rape, Lucy, in an echo of her father’s earlier words, says, “what happened to me is a purely private matter. In another time, in another place it might be held to be a public matter. But in this place, at this time, it is not. It is my business, mine alone.”

“This place being what?” David asks.

“This place being South Africa,” she replies. What also remains a private matter is the result of the rape: Lucy’s pregnancy, which she intends to keep.

The novel’s denouement finds Lucy planning to stay on the farm to raise her child and David, humbled by an abortive attempt to return to Cape Town, working in the animal shelter near her property. Except that it won’t be her property much longer: Lucy has resigned herself to marrying Petrus and forfeiting her land from him in exchange for protection from her assaulter, who is also one of his kinsman. In the final scene, David must come to grips with the fact that he can no longer postpone the death of a suffering stray whom he’d hoped to save: Forgiveness becomes secondary to acceptance and adjustment.

“Disgrace” won the Booker Prize in 1999, and four years after its publication Coetzee was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. In this sense, the novel is hardly unsung. But its wholly unsentimental, achingly sympathetic depiction of a cascading series of traumas has not been recognized for presaging the series of destabilizing crises that has defined the 21st century, and in that it still lives up to its accolades 25 years later. Coetzee never ceases to paint his flawed, hopeless characters humanely, despite the world without responsibility in which they live — a reminder that no state program or political figure can simply sweep away generations of pain and anguish. The process of reconciliation, he understands, is nonlinear, requiring constant vigilance and adaptation. Despite all efforts and moral hand wringing, it may never come to pass. Such is the moral squalor of our geopolitical affairs. Coetzee recognized this a quarter of a century ago. Our politicians and activists are still reckoning with it now.

Lauren LeBlanc is a board member of the National Book Critics Circle.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.