AI and other ghosts haunt Jeanette Winterson’s eerie new story collection

Review

Night Side of the River: Ghost Stories

By Jeanette Winterson

Atlantic Monthly: 306 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“You have no idea how dreary it is to be dead,” says Pamela, and she should know. She was thrown off a balcony by the scion (the “chinless wonder”) of a once-wealthy British family now making ends meet by hosting ghost tourism in their 17th-century pile … and she’s baaaack. She supposedly ran off with a car dealer from New Jersey — so the family is in for a few more shocks than they bargained for.

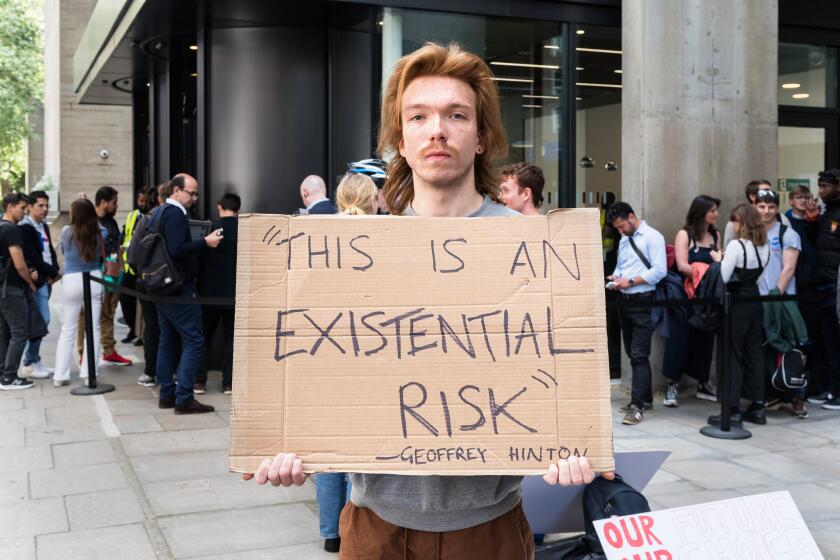

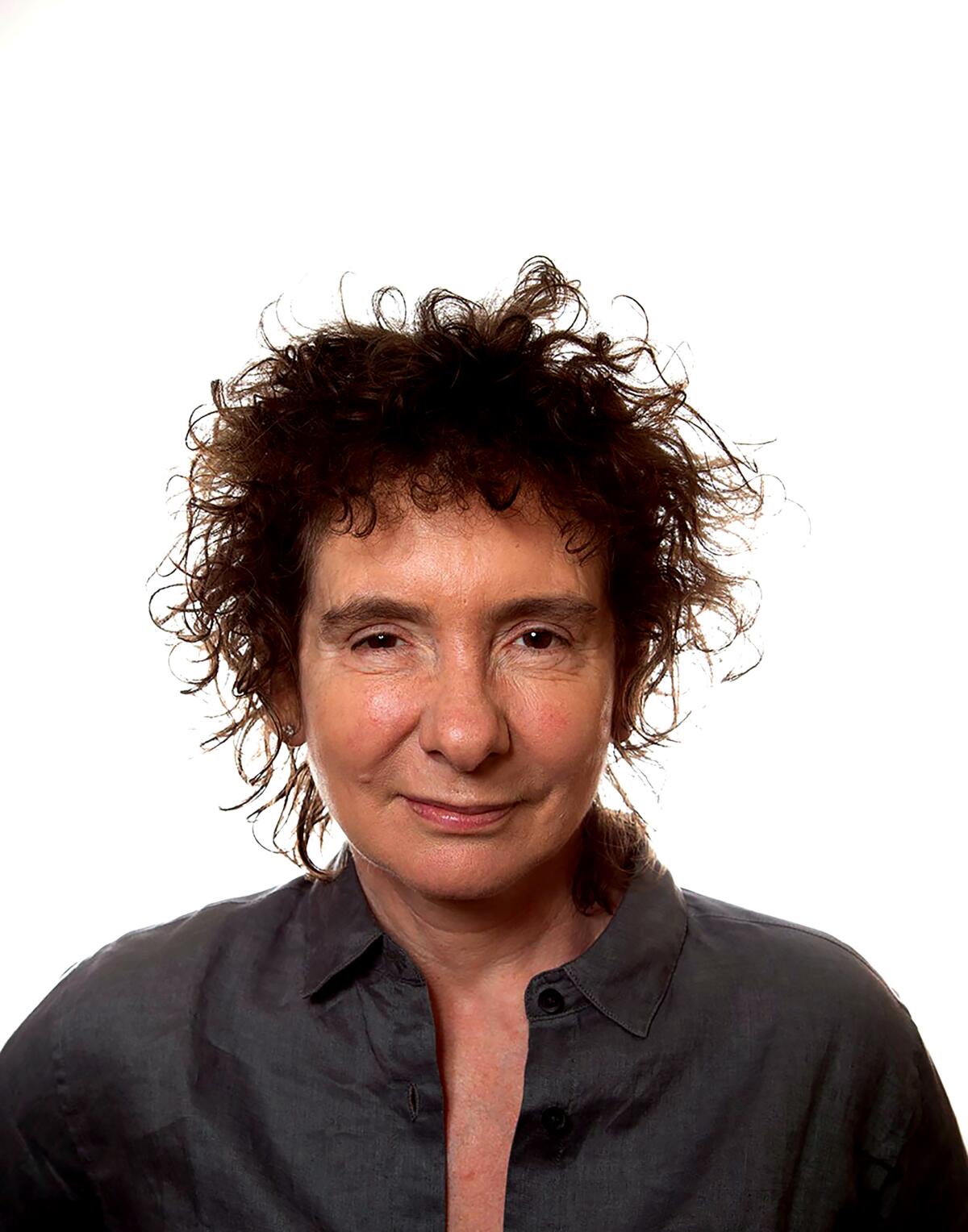

Pamela is one of the spunkier apparitions haunting the pages of Jeanette Winterson’s “Night Side of the River,” a collection of ghost stories that range from campfire-level spooks to speculative reflections on the meaning of life — or, rather, death. In between, there are curious explorations of artificial intelligence, consciousness and the machine dreams of modern life, interspersed with Winterson’s brief descriptions of her own otherworldly experiences. For instance: At 5, she saw her grandmother rise from her deathbed and walk through a window into her rose garden. More recently, she heard “clattering footsteps coming down the wooden stairs” into her room in the 18th-century house she’s been renovating.

In ‘Frankissstein,’ Jeanette Winterson revives the Frankenstein story with a high-tech twist.

Winterson — whose first novel, “Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit,” launched her to stardom in 1985 — wrote in her memoir, “Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?” (2013), about being subjected to an exorcism by her evangelical adoptive parents when she fell in love with another girl. So it’s not too surprising to find her wrestling with the spirit world. She’s also unfailingly interesting (witness her TED Talk), and well worth following into whatever philosophical corner she wants to explore. And in this corner, where the fantastic and the “real” meet as they often do in her fiction, we find the ghostly manifestations of all that haunts us — longing and dread, grief and memory, an empty life and a meaningless death.

There is the sad couple, one mourning and one mourned, each telling his version of the afterlife — the living half feeling (and doubting) the other’s presence, the dead one trying to make himself known. There is the grieving daughter who doesn’t understand why she keeps seeing her dead mother (though we do, having seen “The Sixth Sense”). There is a new widow whose loathsome husband is kept alive by an app installed by her supposedly well-meaning sister. There is an unhappy divorcée finding new love, and perhaps losing herself, in the metaverse. And there are the star-crossed lovers flung to their deaths from a castle, now haunting a happier union. (“You could invite them to your wedding,” the barman/storyteller suggests, and is met with the objection: “They’re dead!” That, the barman says, “never stopped anyone.”)

What animates most of these stories is the idea of free-floating consciousness. This might take the form of the ghost in the machine, whether an avatar unleashed from its human counterpart or an app with a mind of its own. Anyone who’s had perky birthday reminders about dead friends from Facebook will probably not find the JohnApp tormenting the not-really grieving widow much of a stretch. And the sad divorcée’s ever-deeper retreat into her virtual world will make sense to anyone familiar with immersive video games. Winterson just takes the conceit one step further, one step closer to the singularity.

High-profile authors such as Douglas Preston, George R.R. Martin and Michael Connelly are suing tech companies, saying that generative artificial intelligence software is ripping off their copyrighted work. But the legal issues may be complicated.

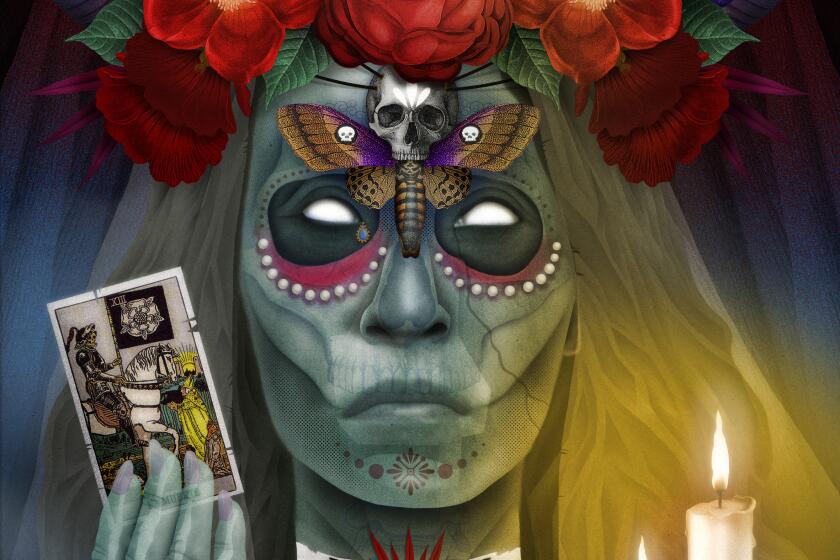

More typical, in these stories and in ghost stories generally, is the consciousness manifest in the lingering presence of the uneasy dead — or, as Winterson renders it, the Dead — a lost lover, a mother mourned, a victim seeking revenge or recognition, or those who simply won’t go away. There are also of course the malevolent ghosts, whose sole function, it seems, is to keep a story going, like a record on repeat: The vile gamekeeper keen on having temporary lodgers learn — and, better yet, reenact — his gruesome tale. The hanged smuggler determined to steer an unsuspecting partygoer to his own watery grave, the titular “night side of the river.”

Often these ghosts are the manifestations of grief, regret, dread or simply memory, and occasionally they bear the familiar trappings of ghost stories: the icy blue eyes (“He fixed me with his eyes like blue lasers.”), the chilling auras (“What is this cold fear that fills me?”), the “swirling fog.” But frequently, Winterson is after something more: the ghost as consciousness in and of itself. “Maybe, after all,” the lingering lover tells us, “consciousness isn’t an emergent property of mind/brain … Maybe consciousness exists, just as the light spectrum exists.”

Maybe. A person can always speculate. And if this means suspending our disbelief and, in some instances, judgment, a bit more strenuously than usual — well, doesn’t that come with the haunted territory?

Whether La Llorona is held up as a form of resistance against oppression, owning her power or reclaiming the monstrous bruja within, the narratives of the wailing woman have endured for centuries, reimagined into a radical icon.

Why ghosts? It’s reasonable to ask. Which might be an answer in itself, as reason can only take us so far when it comes to this thing that every human being comes up against. As Winterson described it in a recent interview, this is “Shakespeare’s undiscovered country, ‘from whose bourn no traveler has returned.’” The lure of ghosts, she says in her introduction, “remains what it has always been: a partial answer to the mystery of death.” Her own answer, playing out in these stories, might not be entirely convincing or all that enlightening — even as the venture manages to be as challenging and entertaining as anything undertaken by this endlessly ingenious writer.

Akins is a freelance editor and the author of five works of fiction.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.