Sly Stone lives to tell the tale of his lifelong journey to heaven, hell and back

Review

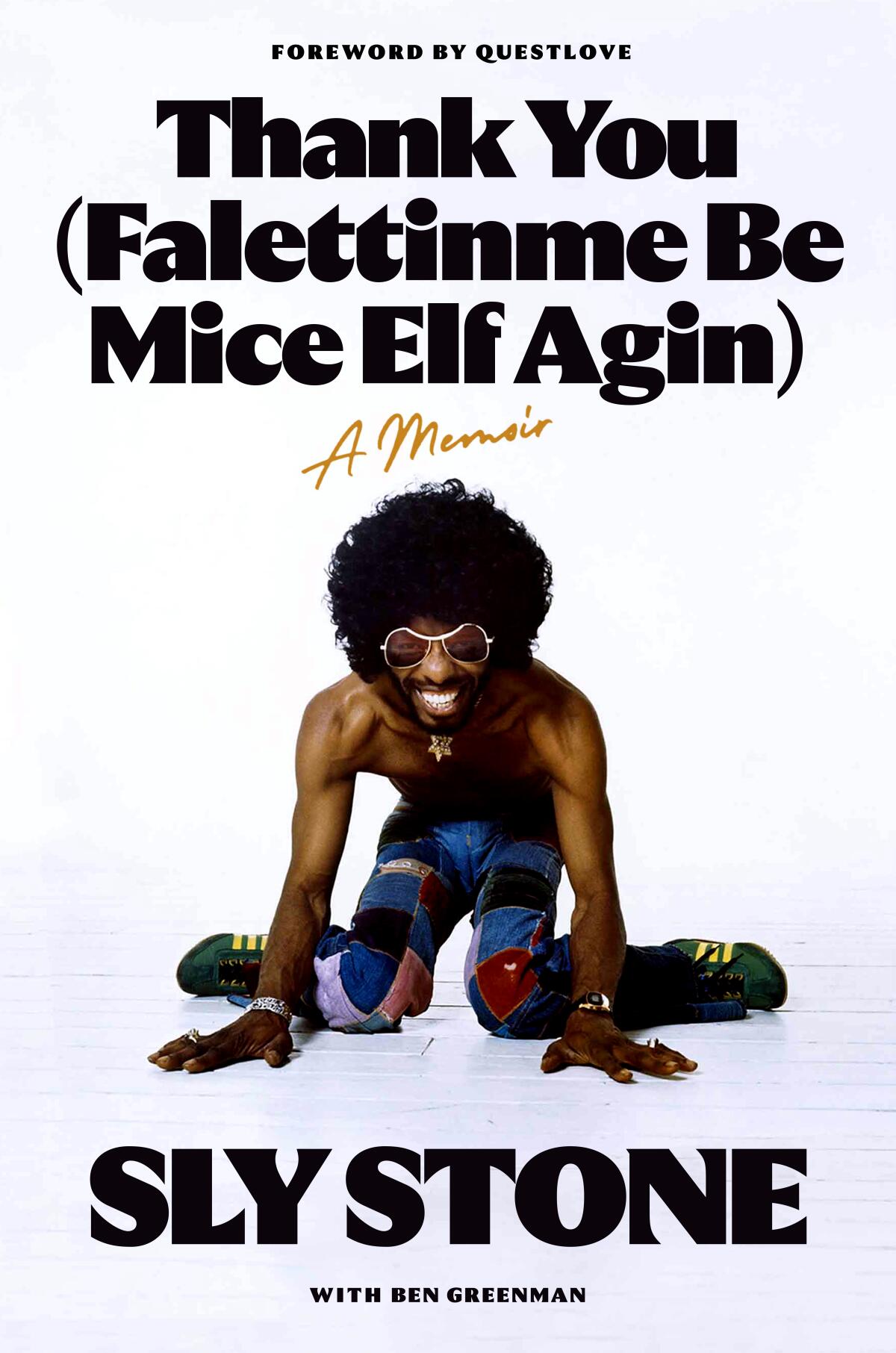

Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin): A Memoir

By Sly Stone and Ben Greenman

AUWA: 320 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

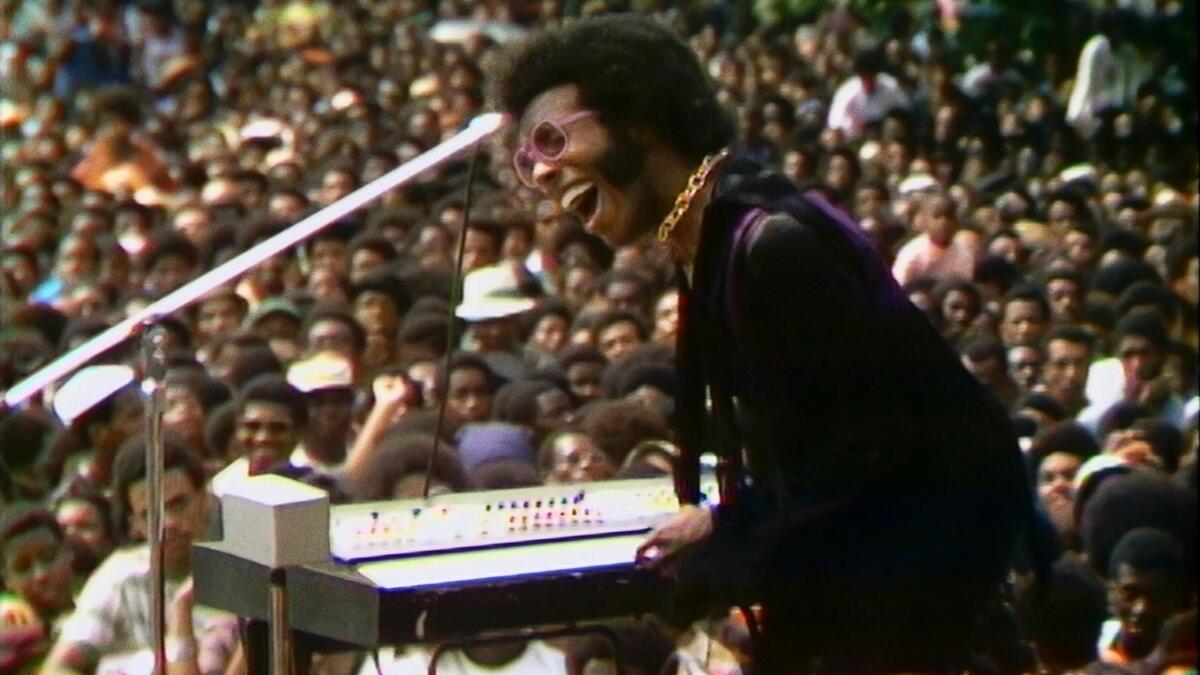

In November 1987, someone in Sly Stone’s camp thought it would be a grand idea to book a two-night stand at the Las Palmas Theatre in Hollywood. The erstwhile superstar, who had notched multiple No. 1 hits during his Nixon-era salad days with his band Sly and the Family Stone, was … well, no one really knew what or where he was. Living in an RV in Chatsworth? Hermetically sealed in a Mulholland mansion with a herd of capybara and king cobras? Or perhaps dead and now, somehow, revived for two nights in Hollywood?

I had to see for myself. I bought a ticket.

Stone booked four shows over those two nights but showed up for only one — many hours late, confused and, to all outward appearances, very high. It was hard to make out the songs, given the guitarist had gone MIA, and Stone’s once-majestic singing voice had lost its gruff amplitude. On the second night, Stone was arrested for nonpayment of child support before he even stepped into the venue. Sly had left the building.

Mary Gabriel’s biography, ‘Madonna: A Rebel Life,’ tracks the story of an artist well-deserving of deep analysis — even if the early years are far more interesting.

In his new memoir, “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin),” Stone places that Las Palmas debacle in its proper context. At the time, Sly writes, he was homeless, having vacated his apartment in the Oakwood complex (his diet: “Top Ramen with chicken franks and onions tossed in”), and looking for help from friends to find a new place to stay.

To read Stone’s memoir, co-written by Ben Greenman as the inaugural title of Questlove’s new book imprint, is to be pulled down into some inner circle of hell reserved for lapsed geniuses with impulse-control issues. Stone’s life has been a litany of violence, abuse, neglect and the financial boom-and-bust cycles that tend to accompany such behavior. All this from a musician and songwriter whose greatest records were spiritual, sexy and funky all at once, the most exuberant radio music in a very robust era for radio music.

He was born Sylvester Stewart in Vallejo, Calif., the son of amateur musicians. “Music was as much a part of our home as the walls or the floor,” Stone recalls. His family sang in the gospel church, and he paid close attention to vocal arrangements, the way the guitarist drove the band, the drama of dynamics. He studied music at junior college, mastered every instrument he could get his hands on, then hustled up gigs as a radio DJ and songwriter-for-hire.

In the process he meets a clutch of commanding musical personalities — saxophonist Jerry Martini, trumpeter-vocalist Cynthia Robinson, drummer Greg Errico, bassist Larry Graham. Together with his brother Freddie and sister Rose, he starts Sly and the Family Stone. Stone’s powerful, racially integrated band gets to work, recording four albums in as many years. Stone the songwriter finds his groove, writing a series of life-affirming hits: “Everyday People,” “Stand!” and “You Can Make It If You Try.”

Leon Russell wrote a handful of modern standards and worked with artists from Dylan to Clapton to Streisand to Elton. A new tribute LP heralds the Leonaissance.

In the memoir, Stone provides tantalizing crumbs of insight into his oeuvre. “I Want to Take You Higher” was a slight reworking of a song Stone had written for Billy Preston called “Advice.” The “na-na-na” breakdown of “Stand!” was added after Sly played the song live without it, only to discover it “wasn’t producing the necessary effect.” There are insider tidbits like this sprinkled throughout, but Stone never really digs too deep into his life or art; he’s content to skim over the surface.

By 1969, Stone had his creative stride. “I had so many ideas for songs that year,” he writes. “Simple songs, complicated ones, songs I thought could be standalone singles, experimental things.” He worked from the bottom up: “I’d get hold of a rhythm, get it down, and then listen to it again and again as the song grew around it. Words would come in, countermelodies, ideas for arrangements.” He was also ingesting a mega-pharmacy’s worth of drugs.

It was a period of both private bleakness and public greatness. His 1971 masterpiece “There’s a Riot Goin’ On” was written and recorded during Stone’s gonzo, decadent peak — holed up in a Bel-Air mansion with a pet baboon, endless lines of cocaine, strange men carrying firearms, a bank safe for his choicest pills. Drummer Errico had quit the band out of sheer disgust, so Sly pulled out a Maestro Rhythm King drum machine in the bedroom and started tinkering, then laid down guitar parts and vocals. From this emerges his masterpiece “There’s a Riot Goin’ On” — surely the strangest, most beautifully funked-up record of its era to go platinum. There’s also another No. 1 single, “Family Affair.”

Despite his erratic behavior, Stone can’t miss — at least for a while. In 1973 he has another Top 20 hit, “If You Want Me to Stay.” A few months later, he marries Kathy Silva in front of 20,000 screaming fans at Madison Square Garden.

This article was originally on a blog post platform and may be missing photos, graphics or links.

The drugs keep coming, but the hits don’t; by the mid-1970s, Stone is recording music that, in his former life, he might have rejected as beneath him. He shows up hours late for shows or not at all. By 1975, he can’t even sell out a third of the house at Radio City Music Hall. In what may be the strangest second act in a music memoir, Stone goes on at length about his career as a TV talk show guest sitting beside Dick Cavett, Geraldo Rivera, Mike Douglas — amiable anecdotes that have the unintended effect of illustrating just how quickly Stone the musical supernova had shrunk down to normal celebrity size, a seat filler for banal TV chat.

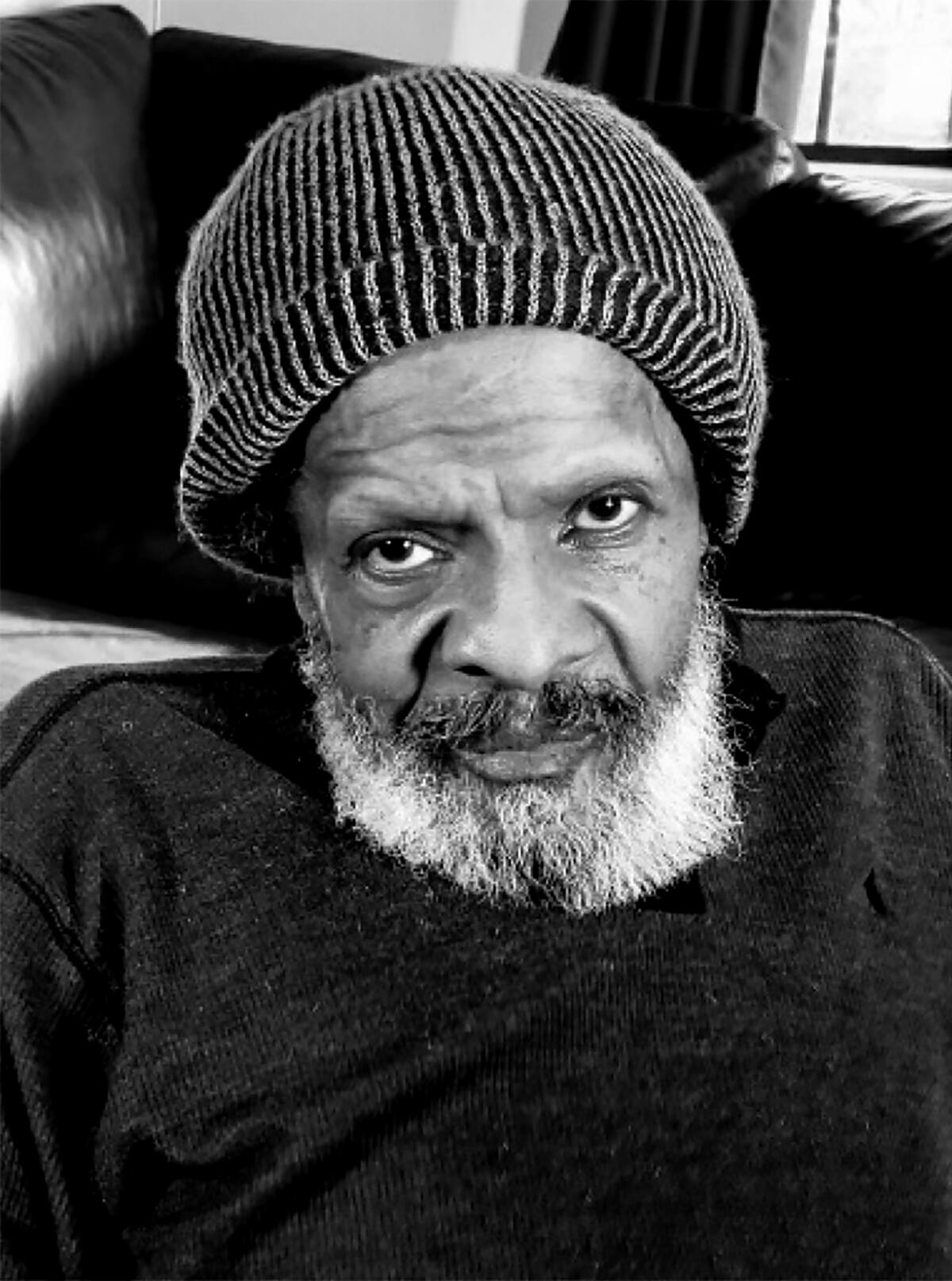

Many hospital visits and failed rehab stints later, Stone, now 80, is clean, living a quiet life in the San Fernando Valley. Of his drug habit, he writes, “I should have stopped sooner. Much sooner: less dust and powder, fewer rocks and pipes, enough days given back that might have added up to years.”

Amen. That Las Palmas show in 1987 wasn’t just weird, it was also deeply sad. But this bracing if somewhat superficial memoir is a reminder that even long, turbulent rides are capable of soft landings.

Weingarten is the author of “Thirsty: William Mulholland, California Water, and The Real Chinatown.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.