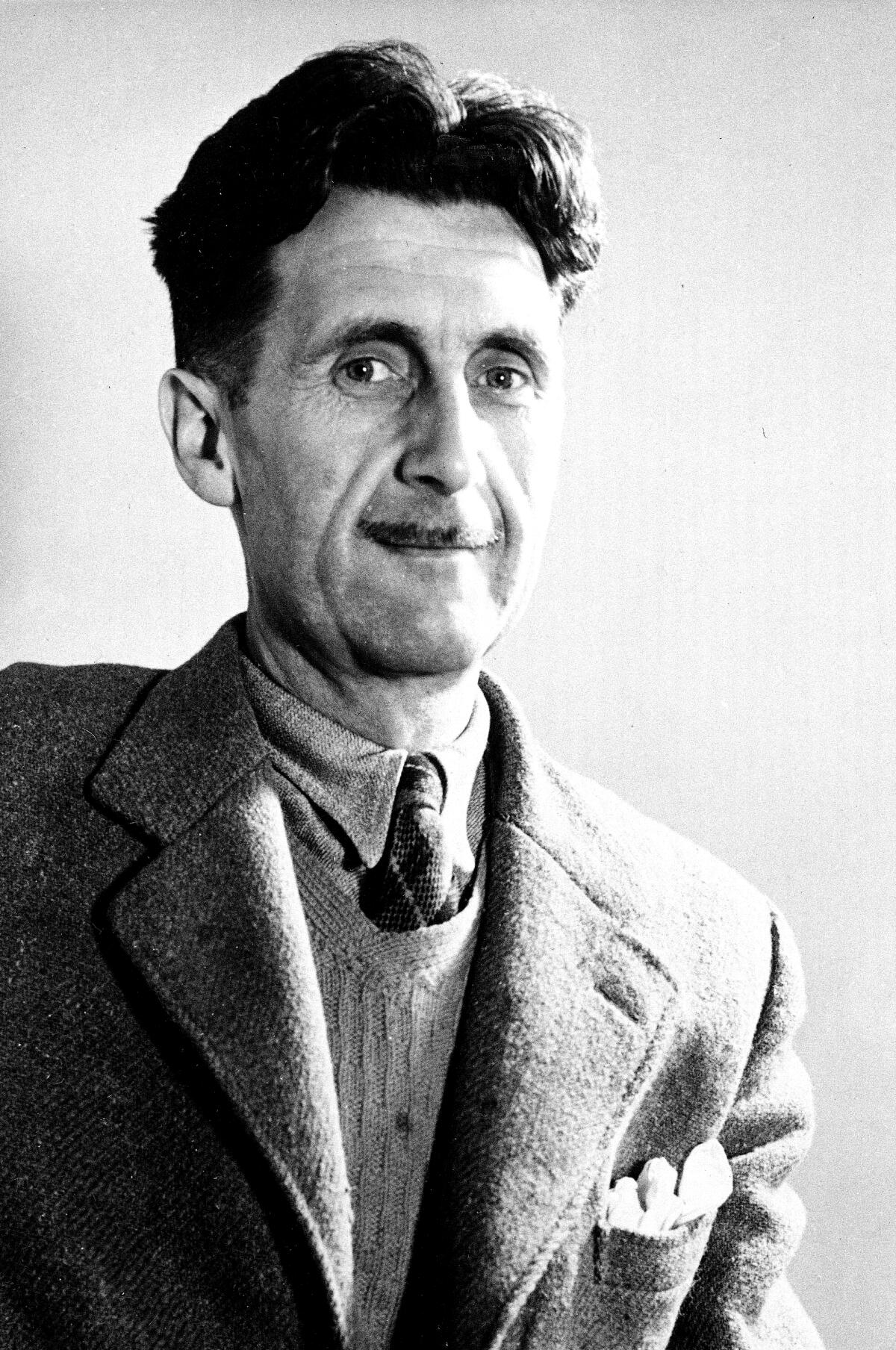

Was George Orwell’s monstrous behavior responsible for his wife’s death?

Review

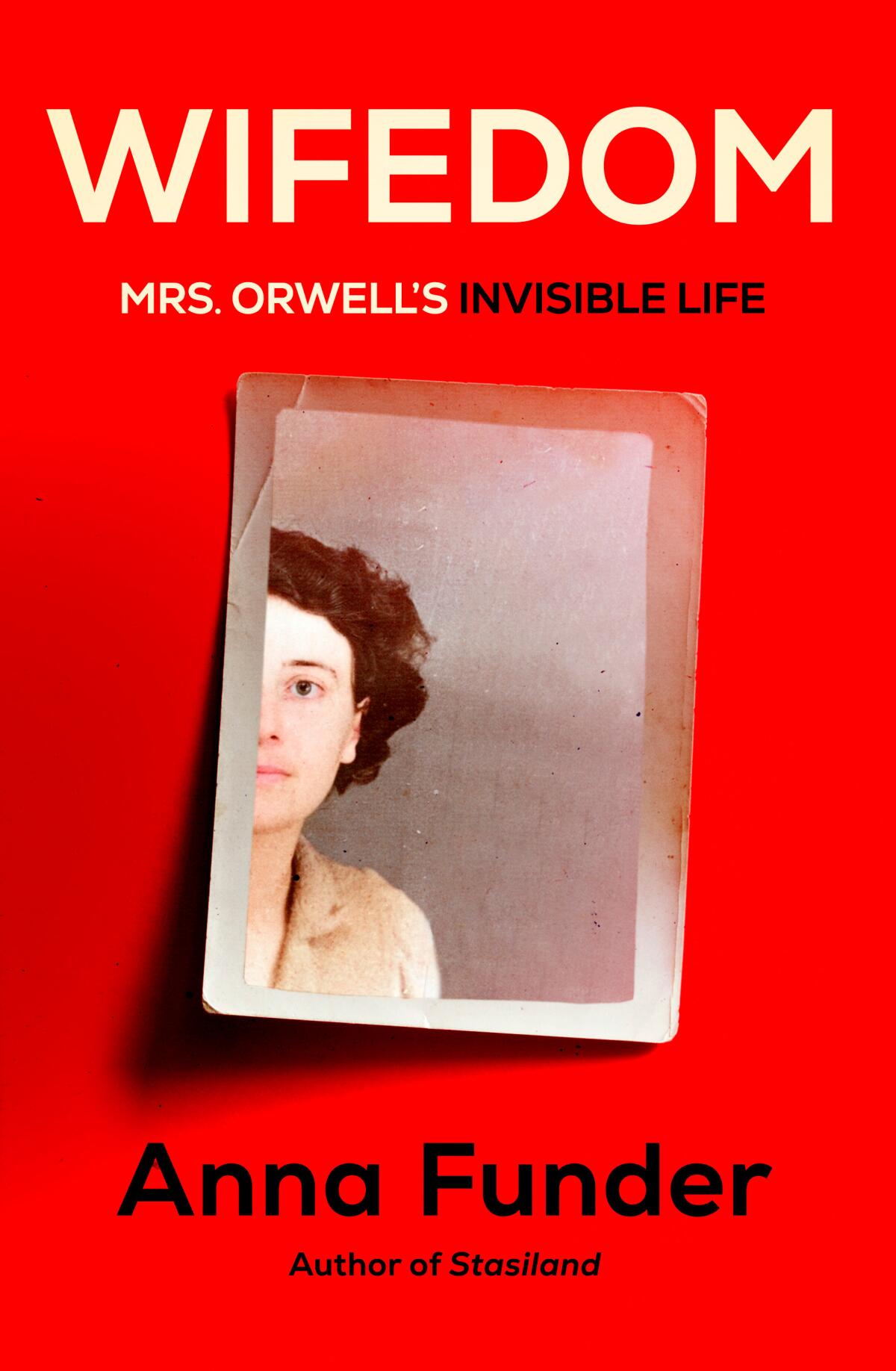

Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell's Invisible Life

By Anna Funder

Knopf: 464 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Recently, there has been much discussion of the artist “in her own right.” The obituaries for Françoise Gilot describe an artist “in her own right,” as well as a lover to Picasso. A new book on painter Gwen John focuses on her work even as she is remembered as a lover of Rodin. Painter Celia Paul’s two books, “Self-Portrait” and “Letters to Gwen John,” grapple with her identity as a painter in addition to being the lover of Lucian Freud. Gilot, John and Paul are all artists, full stop. They are also survivors; they continued to work and live when many female artists either stopped working or died.

Eileen O’Shaughnessy Blair did not survive. She died at the age of 39, under the knife for a total hysterectomy after years of excruciating pelvic pain and bleeding. Her infant son was with relatives, her husband off in Paris visiting Ernest Hemingway. Letters sent to her spouse — on the cost of the surgery, whether or not her life “was worth the money” — went unanswered. While her family begged her to wait for a more experienced surgeon, she went with a cheaper doctor and died alone. She is buried under the epitaph “Wife of Eric Arthur Blair.” Eric Arthur Blair — better known as George Orwell.

Of course Big Brother isn’t just watching us anymore — he’s listening to our cell phone and FaceTime conversations, friending us on Facebook, following us on Instagram (just as we are often following Him).

Anna Funder’s “Wifedom” examines this and other deadly erasures. A writer and historian as well as a wife and mother, she knows it well. She obviously loves Orwell’s writing. But in her research, Funder uncovers his invisible wife, Eileen, whose story is as necessary for Funder to tell as it is instructive to her personally. “I would look under the motherload of wifedom I had taken on,” she writes, “and see who was left.”

With the precision of a historian, Funder cobbles together scant details to reconstruct a life. And with the imaginative force of a novelist, she speculates in clearly sign-posted moments on what that life was like. Some of the horrors she uncovers are known in vague outline, but much has been willfully evaded by Orwell’s biographers or explained away in compounding acts of misogyny. Eileen’s letters to her friend Norah Symes Myles were discovered in 2005. For the first time, in this book, Eileen is given a voice — her voice.

Eileen was educated (she went to Oxford), and politically motivated. She worked for the British Independent Labor Party while Orwell was soaking up the action at the front during the Spanish Civil War.

The painter known to many as Lucian Freud’s one-time muse writes of her own muse, her mother, and provers herself a masterful writer as well.

In a lengthy section of the book, Funder describes Eileen’s dangerous work during that war and her essential help to Orwell. If you read “Homage to Catalonia,” Orwell’s book about the war, you would barely register that Eileen was there, despite the fact that she typed the manuscript and provided many of its anecdotes. Orwell was shot through the neck standing in a trench, and Eileen was nearly captured and executed as a spy. “Orwell spends over 2,500 words telling us of his hospital treatment without mentioning that Eileen was there,” Funder writes. “I wonder what she felt, later, as she typed them.”

For the record:

10:53 a.m. Aug. 21, 2023An earlier version of this article included an incorrect photograph of George Orwell’s wife Eileen O’Shaughnessy Blair. The woman pictured was his second wife, Sonia Orwell.

Funder gives us Eileen’s actual writing — a description of their life in Africa, where they stayed for a while in hopes that the warm climate would be good for his health. Orwell used her description in his essay, “Marrakesh.” Funder puts both versions side by side and describes hers as “pithily alive.” In other words, Eileen’s writing is better.

Orwell, like D.H. Lawrence, had a violent, sadistic relationship with women. Overtones of repressed homosexuality appear in both men’s work and biographies. Readers will find multiple allegations of sexual assault on Orwell’s part, as well as disturbing betrayals like sleeping with Eileen’s good friends. He didn’t tell his wife he was sterile until well after they were married; he also kept his diagnosis of tuberculosis a secret, despite frequent hemorrhages that endangered the health of anyone around him, including his young adopted son.

He tried to join the war effort in 1939 but was rejected for health reasons. Through her full-time job at the Ministry of Food, Eileen supported both of them despite her own rapidly declining health. When her beloved brother was killed in action, Eileen suffered cruelly. Orwell started writing “Animal Farm,” based on an idea of Eileen’s, and embarked on several sexual affairs. On the scheduled date of their adoption court hearing, Orwell was in France. “Eileen has to drag herself, bleeding, in pain and alone, into court to appear before the judge,” Funder writes.

A prolific painter, Gilot was likely more famous for her turbulent relationship with Pablo Picasso — and for leaving him.

Eileen did not appear to have writerly aspirations, though she did act as Orwell’s note taker, first reader, editor, typist, agent and more. Funder’s aim is not to show how great a writer she was but to show how a human being can be utterly destroyed and then erased. And how a beloved author could have been a detestable human. “Any writer could fall into the gap between what a reader imagines of them, and who they think they are,” Funder writes. “And a woman might live there.”

Considering how little information Funder has to work with, “Wifedom” is a spectacular achievement of both scholarship and pure feeling. The sections of Eileen’s life that are imagined by Funder have a decidedly Woolfian flair. But even after Eileen’s death, she is continually being erased. If Eileen is nowhere in Orwell’s writing, then there is no Eileen.

Learning that Orwell didn’t show up to the inquest into Eileen’s death or even read the coroner’s report, Funder uses his words against him: “Totalitarianism demands the continuous alteration of the past, and in the long run probably demands a disbelief in the very existence of objective truth.”

She goes on: “If he doesn’t read the inquest report, he can alter the past with a story. … His fear was perhaps not that he would find fault with the surgeon, but that he would find it with himself.”

“Wifedom” doesn’t ask if a woman has a right to be an artist “in her own right” but rather if the art created by men is worth the suffocating domestic violence and killing anonymity often suffered by their wives. Not the right of the woman artist to exist but the right of a woman to live.

Ferri is the owner of Womb House Books and the author, most recently, of “Silent Cities San Francisco.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.