Page to Screen: John Cameron Mitchell brings the spark to ‘City on Fire’ on Apple TV+

By the time it came out in 2015, Garth Risk Hallberg’s novel “City on Fire” was notorious for its scope of ambition, unheard-of advance and early acquisition by Scott Rudin. Upon release it sold well but received middling reviews. Predictably, it landed in development purgatory.

The text was set in the New York City of 1976-77, a well-trod milieu in TV and film. For their Apple TV+ miniseries concluding Friday, Josh Schwartz and Stephanie Savage adapted the story to take place in 2002-03 — or a muted, blurry version thereof. The book, more than 900 pages, was an exhaustive inventory of its ensemble’s lives, each in some way an emblem of its time. It was also a Dead White Girl thriller.

Predictably, the showrunners resolve the book’s ambivalence by closing in on the crime story, sacrificing much of its idiosyncrasy. (They’re best known for “Gossip Girl” and “The O.C.”) The new series’ quicker pace tightens the main narrative thread and builds momentum the book sometimes lost. But the mise-en-scene suffers inexplicably and lacks resonance with our more recent era.

The plot centers on the shooting of an NYU freshman, Samantha, the night of a downtown rock show and an uptown penthouse soiree. When Sam leaves the show to see someone at the party, an unidentified acquaintance pursues her into Central Park, fires twice and leaves her for dead. As Sam lies in a coma over the following weeks, investigations home in on ties between the downtown musicians, led by a self-styled militant, and the Hamilton-Sweeney tycoon clan hosting the party that night.

The book opens at the holidays, with its critical action on New Year’s Eve, then revisits the summer that led there. The show does the inverse: The shooting takes place on the Fourth of July, then we return to the previous winter. The series’ final installment invokes the regional blackout of August 2003, echoing that of the book’s late chapters set in July 1977.

The band playing downtown on the fateful night once featured William Hamilton-Sweeney, junkie painter son of the family. His replacement is Nicky Chaos, a pyromaniacal Svengali ruling a cadre known as the Phalanx. Sam’s friend Charlie joins their ranks to seek the truth about her shooting. William’s earnest boyfriend, Mercer, and dutiful sister, Regan, figure into the picture uptown. Amory Gould is the “demon brother” of William and Regan’s stepmom, busy conducting a coup of his own. He hires Nicky to advance his development plans by setting fires in the Bronx and blackmails Regan’s ethically challenged husband, Keith, into handling the payments. Thus Keith encounters Sam and gets involved with her, never mind that she’s in college. When Nicky’s volatile alliance with Amory breaks down, he plots revenge with stolen explosives, and Sam risks exposing the Phalanx.

The series changes the story’s backdrop from punk to indie rock, from NYC’s bankruptcy crisis to post-9/11 concerns. Popular New York bands like the Rapture and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs form the soundtrack, with a helping of then-resurgent downtown acts from the story’s original period (Bush Tetras, Television, et al.). Charlie’s dad died in the World Trade Center, and we briefly see the kids walk past Ground Zero. “See something? Say something” flits through the zine-style opening sequence. The heroic cop, who survived polio in the book, is an Arab American disabled by a hate crime in the show’s backstory.

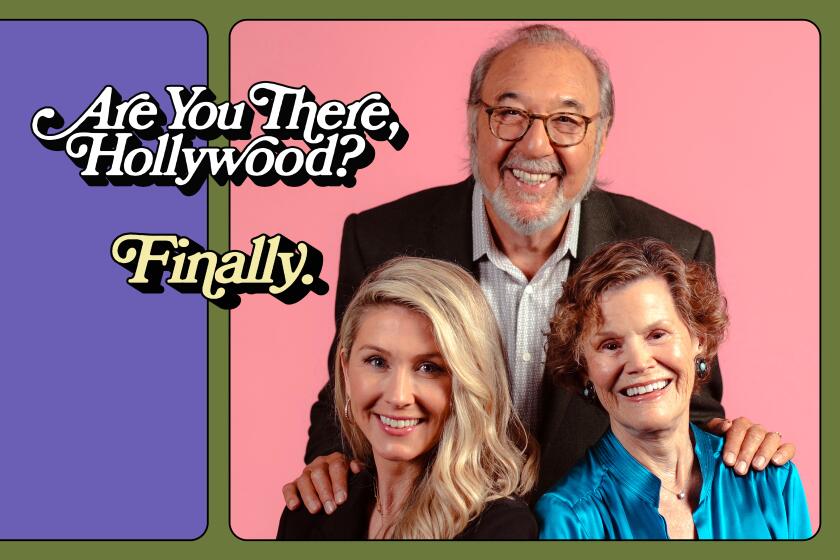

Judy Blume, James L. Brooks and Kelly Fremon Craig hash out — and argue over — how they finally came to adapt “Are Your There God? It’s Me, Margaret.”

While the book’s enchantment with its setting could feel fetishistic, the show’s use of a memorable era feels strangely amnesiac. The time frame coincides with the invasion of Iraq that triggered major protests in Manhattan. The freshly militarized NYPD put snipers on rooftops for peace marches, raided convergence spaces and conducted mass arrests (I had the personal pleasure). It was the time of the government mantra, “If you’re not with us, you’re against us,” and those who ran afoul of the Patriot Act faced FISA warrants and “no-fly” lists. That there’s no acknowledgment of any of this, in a show dealing with cops and a group like the Phalanx, is ahistorical and downright bizarre.

Like Sam, I was a college music journalist and zine author who joined a radical collective and moved into an industrial squat. It was a potent time for both activism and underground music, but you wouldn’t know it watching the show. Actor-musician Max Milner plays Nicky with enough sex appeal and actual musicality that perhaps his credo needn’t exert the same pull it does in the book, where it’s better developed. Still, it’s hard to imagine that Sam followed him for over six months on a platform of “Burn It Down” and something vague about gentrification. Charlie sees through him in less than six weeks.

Yet one thing carries the series. In a surprise turn, John Cameron Mitchell plays Amory, with Cruella de Vil hair and nearly visible fangs. For queer kids of the show’s era, Mitchell’s “Hedwig and the Angry Inch” and “Shortbus” are such cherished cultural touchstones, it’s initially hard to see him as other than a sort of theatrical gay Santa Claus. (In fact, he workshopped “Hedwig” at the club where some of the series’ scenes are set.) But he clearly delights in his newfound malevolence, and his performance as a bespoke, camp Machiavelli supplies the humor the book sorely lacked.

In Hallberg’s text, Richard, an alcoholic journalist and buddy of the virtuous cop, takes an interest in Sam’s story. After discovering the arrangement behind the fires, he winds up in the harbor. His Californian neighbor, Jenny, is assistant to William’s gallerist. She’s a character with depth in the book but a peripheral art groupie in the show, where William takes over the Nancy Drew beat.

In the original story, Regan’s past rape led to a difficult pre-Roe abortion. In the series, it leads to an incredible adoption coincidence. It’s a ground-brushing piece of narrative fruit that Hallberg — not a paragon of restraint — managed to resist in his doorstop tome. Mercer, who shares none of William’s privilege, is one of the book’s main protagonists, but the show spends sadly little time in Mercer’s world. Without more access to his life and Regan’s, it’s hard to understand why they’re with chronic dissemblers like William and Keith.

Yet the series preserves at least a dozen minor characters and several tangential storylines — like the cop’s fertility crisis, and his colleagues, who are no longer racist thugs — adding or expanding several more, like a pointless red herring involving Regan’s son. We get every confirmation, confrontation and confession that Hallberg withheld, and the dead don’t stay dead in the series. We even see Amory lose his cool in a gratifying tantrum by Mitchell, who chews up a limo interior before going full-on Scooby Doo villain.

To the extent that the book was a disguised genre thriller, the show does a serviceable job of taming Hallberg’s story to the small screen. Mitchell’s mischief helps distract from the deficit of war-on-terror verisimilitude. Ideally, someone will compress his appearances into a highlight reel, NoHo Hank-style, for curious fans who haven’t eight hours to burn on the couch in the middle of Pride month.

'City on Fire'

Rated: TV-MA

Playing: Apple TV+

Johnson writes The Times’ Page to Screen column. Her work has appeared in the Guardian, the New York Times, Los Angeles Review of Books, the Believer and elsewhere.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.