True Mexican stories become legends in Fernanda Melchor’s genre-defying nonfiction

Review

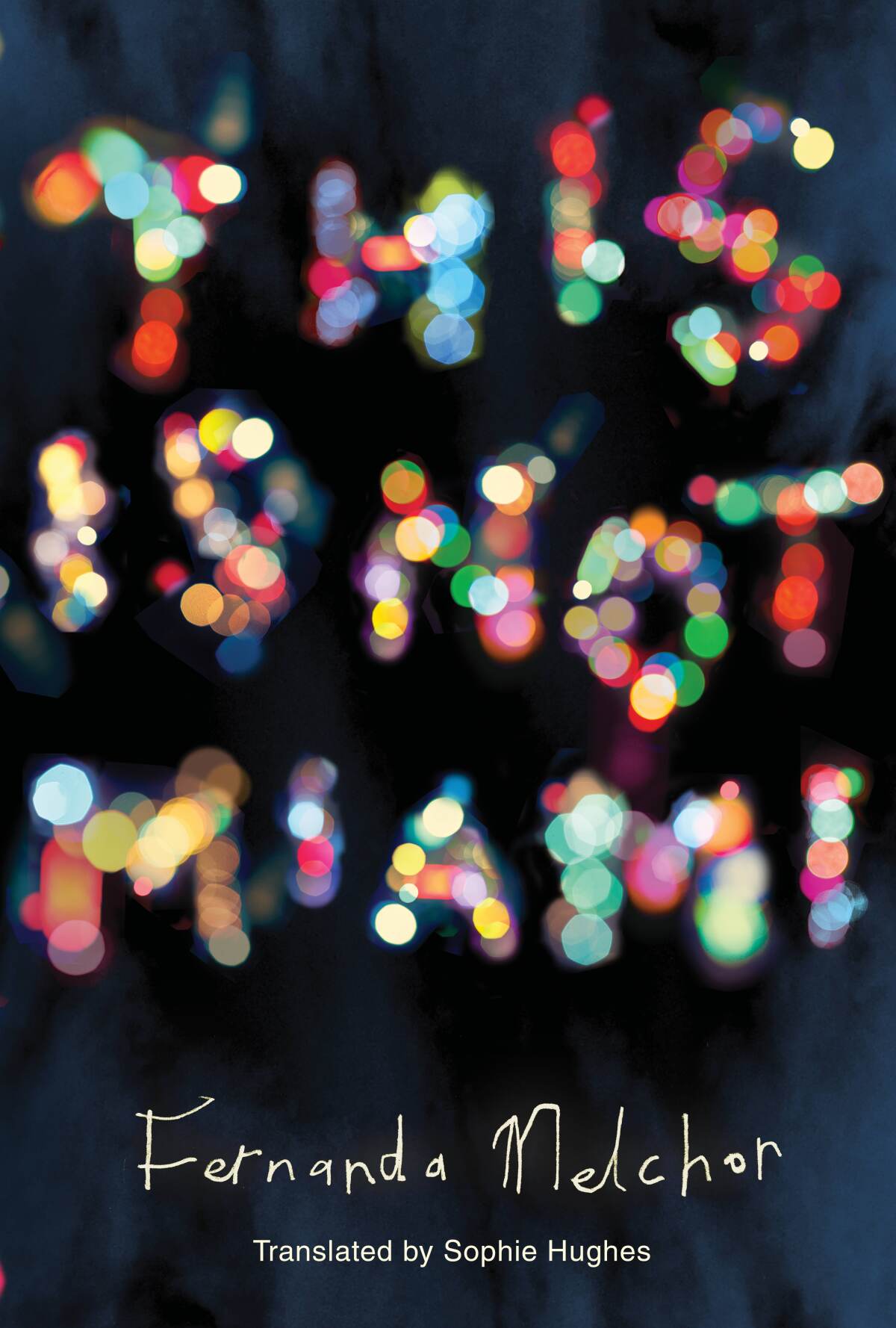

This Is Not Miami

By Fernanda Melchor

New Directions: 160 pages, $16

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In “This Is Not Miami,” her new book of not-quite-nonfiction, Fernanda Melchor tells the true story of a lynching in her home of Veracruz, a state on the Gulf Coast of Mexico. In 1996, a man named Rodolfo Soler stood accused of rape and murder, and Melchor relates the townspeople’s vengeance — torturing him and burning him alive — in prose as cool as the events were grotesque. “Once he’d fallen to the floor they cut off his left foot with a machete to see if he was still alive,” she writes, “and since he continued groaning, they poured another can of fuel over him.”

Steely resolve in the face of violence has been a hallmark of Melchor’s remarkable and still-nascent career. “Hurricane Season,” her first novel translated into English and a finalist for the 2020 International Booker Prize, explores the demise of a Veracruz “witch” in a milieu of drugs, violence, porn and other assorted vices. Last year’s follow-up, “Paradais,” was a slim but potent novel about a sexual assault, from its cold-hearted planning to agonizing execution.

We asked four book critics to pick their favorites books published in 2022. Here are Mark Athitakis’ top 5 novels of the year.

In short order, Melchor has established a few clear themes in her work: The way misogyny, violence and the drug trade are braided; how fear forces bystanders to watch their words; and how the resulting euphemisms and silences create a kind of folklore around a place. “Hurricane Season” is constructed of run-on stories, thick with rumor, about the witch at its center; “Paradais” features a supposedly haunted house that serves as a sin eater for its characters.

Consistent with her interest in mythology, the line between truth and fiction gets fuzzy in “Miami.” Presented as “narrative nonfiction” but formally loose, it’s deliberately disorienting. Melchor’s pushing the reader to reassess the premises around which we make judgments about people, countries or entire regions.

Melchor is up-front about her intentions. In an introductory author’s note, she says her goal is “to tell stories in what I regard as the most honest way possible: by accepting language’s inherent obliqueness and using it to the story’s advantage.”

The people and incidents she writes about are real, she writes, but she wants to acknowledge the subjectivity that’s inherent in even the most objective writing, “the fiction inherent in every construct of language.”

This is a tricky business: One journalist’s “I am thoughtfully exploring the inherent shortcomings of language” is another’s “I’m going to dance around facts that are inconvenient to me.” American literary journalism is littered with problematic cases: Truman Capote’s true-crime “nonfiction novel” “In Cold Blood” had factual errors and invented scenes; Joe McGinniss’ “Fatal Vision” had its investigative shortcomings autopsied by Janet Malcolm and Errol Morris; John D’Agata’s reportage on Las Vegas, published as “About a Mountain,” sparked a battle between the author and his fact-checker so heated and wide-ranging that they wound up collaborating on an entire book about it, “The Lifespan of a Fact.”

In all these cases, the central concern was what’s gained and sacrificed when you try to turn fact into art. What this means for Melchor, it seems, isn’t so much an urge to fabricate as an effort to trace how these grim stories become legends, how our imaginations reshape bleak realities.

From a bestselling migration memoir to an acclaimed novel of suburbia, political poetry and essays and on and on, Salvadoran writers are having a big moment.

Sometimes the reshaping is musical: Soler’s tragic tale, for instance, is titled “Ballad of the Burned Man” and introduced through a song about him. Sometimes it’s metaphorical: In the opening personal essay, titled “Lights in the Sky,” Melchor recalls watching strings of lights in the night sky with romantic notions of imagining space aliens “searching for a more hospitable planet.” Only later does she realize that the lights are most likely narco planes.

Melchor’s stories intensify from that relatively innocent opening: The refugees in the title story were hoping to make it to America as stowaways but departed one port too early, “covered in welts that looked like whip marks.” Melchor recalls that, on a date, a man told her about a haunted house and an exorcism, a story she bounces off her own love of William Peter Blatty’s “The Exorcist,” which she’s read “about ten times.” Another man tells her about how the Los Zetas cartel struck such fear in locals that “you called them ‘the last letter guys,’ as in zee for Zeta.”

That piece is written in second person, which both distances it from conventional reportage and demonstrates the urge to avoid ownership of the crisis: The problem is “yours,” not mine or ours. (Sophie Hughes, Melchor’s English translator for three books, captures the deadpan, unflinching voice Melchor strives for, regardless of her stylistic or structural shifts.)

Melchor’s talent for exposing storytelling tropes is clearest in the collection’s strongest piece, “Queen, Slave, Woman,” which determinedly scours off the simplistic tropes and assumptions that get attached to true-crime stories. Melchor relates the case of Evangelina Tejera Bosada, a Veracruz woman who in 1989 was convicted of killing her two sons, ages 2 and 3. The tale of the “Carnival Queen” brought low by drugs made her a magnet for all sorts of social anxieties, Melchor writes: fear of the cartels, desire for female victims, hunger for ghost stories. Melchor isn’t relitigating Bosada’s case so much as looking at why we can’t let go of it. What she finds is “a society that professes to be an enclave of tropical sensualism but deep down is profoundly conservative, classist, and misogynist.”

Novelist Silvia Moreno-Garcia brings ‘The Daughter of Doctor Moreau’ to the L.A. Times Book Club Sept. 27

Melchor isn’t inventing anything in broad strokes. Cartel violence has long been a fact of life in Veracruz. Soler’s lynching has been well documented. So has Bosada’s trial and conviction. She’s not playing with facts so much as how facts are delivered — oral history, first person, second person, ghost story, legend. A lesser journalist massages details to more perfectly fit a narrative. Melchor is doing something more like the opposite: playing with form to expose the lies, hypocrisies, hatreds and oversights that soften or avoid the reality of human evil. Melchor isn’t claiming to know the whole story. But what she means to say is that we should think twice before we do as well.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.