Braving a blizzard to meet the most promising (and most offline) young writer in the West

On the Shelf

Thrillville, USA: Stories

By Taylor Koekkoek

Simon & Schuster: 208 pages, $17

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

I had just crossed the border from Washington to Oregon when the snow began to fall.

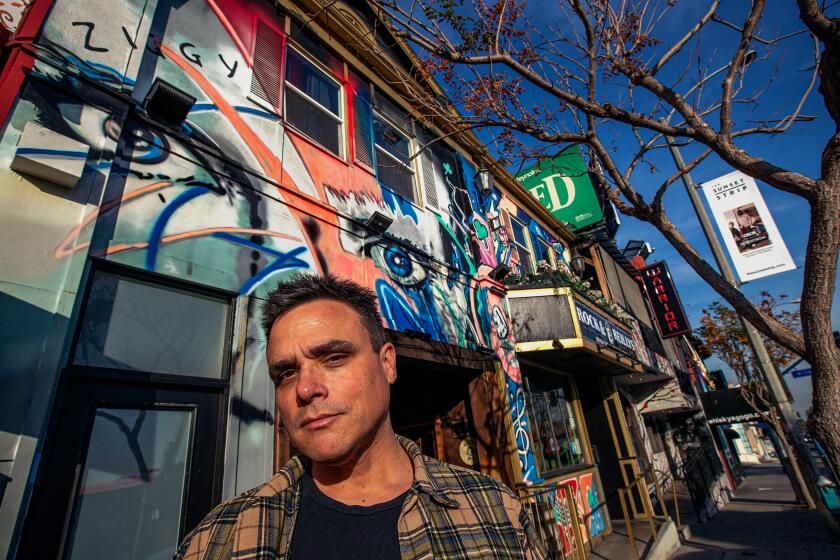

Renting a car in Seattle and driving down to interview Taylor Koekkoek, the author of the stunning debut short-story collection “Thrillville, USA,” seemed like a good idea back in sunny Southern California.

But by the time I reached Portland, the snowstorm was approaching blizzard conditions, swirling around the towering pine trees and blanketing the highway. The map on my iPhone lit up with traffic accidents. My mini-SUV shivered like a chihuahua when trucks roared through the storm. A prudent driver would pull over and scrap the interview; a reckless one would keep going.

It’s the kind of dilemma the characters in Koekkoek’s stories often face, where one bad decision cascades into an avalanche of regret: doing opiates while working at a sketchy roadside carnival, letting a complete stranger park a borrowed van, taking a group of pilots-in-training out for a night of drinking on the eve of an important test.

In his blurb for the book, legendary short-story writer Wells Tower praises Koekkoek’s “painful tales of calamity and waywardness” — a situation I now found relatable.

Muñoz’s stories are peopled by furtive figures who grapple with survival and loss. His most stunning depiction, however, is of the Central Valley itself

It was these stories that pushed me to seek out Koekkoek in the flesh. A Google search reveals very little about the writer: a few published stories, no social media trail, author bios at a handful of universities that feature the same photo of an amiable-looking young white man in a Hawaiian shirt. If one were to make up an identity for a fictitious writer, the results would resemble something like the sum total of Koekkoek’s online experience.

His publications, however, are legit. The Los Angeles Review, Ploughshares, the Paris Review. How was it that, in this age of relentless self-promotion and branding, someone who wrote stories of such uncommon brio operated almost completely under the radar?

I finally reached Koekkoek’s address several hours late. His name (pronounced Cook-cook) is Dutch, he explained after welcoming me into the home he recently bought with his wife, the writer Joselyn Takacs, but he has no idea what it means.

Although he lives about a mile from his childhood home, Koekkoek took a wayward path to becoming a published writer. After taking a single creative writing course at the University of Oregon in Eugene, he was torn between getting an MFA in creative writing and becoming a lawyer.

Much to his surprise, he was accepted into the highly competitive MFA program at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “I decided to go where the real money’s at,” Koekkoek joked. He conceded he would have been a terrible lawyer. “I would have hated it.”

At Hopkins, he studied with the writer Eric Puchner, who was impressed with Koekkoek’s mindset. “[H]e was willing to go back and just keep revising and revising and revising,” Puchner said over the phone. “The students … who have gone on to become writers and publish books aren’t necessarily the most blindingly talented; they’re just the most dogged and are able to steel themselves against rejection.”

After his ‘L.A. Confidential’ adaptation was canned, Jordan Harper decided to write his own L.A. thriller. ‘Everybody Knows’ is Hollywood noir made new.

Koekkoek’s writing steadily improved during his time at Hopkins, Puchner said, imbuing stories with his own experiences in Oregon. “I saw his work go from being hilariously satirical to something that actually could move somebody. It was kind of a dramatic transformation.”

Koekkoek was a bit more subdued about his development: “I think a lot of us have that stage where you’ve read a little too much Hemingway.”

Next, he moved to Bend, Ore., where he lived with his twin brother. “I didn’t have a real direction,” he recalled. “I was flailing about. I was making questionable decisions.” It was during this period that Koekkoek wrote the collection’s title story, “Thrillville, USA,” which is based on an actual amusement park in the town of Turner, Ore. He and his brothers had fond childhood memories of visiting Thrill-Ville, which shut down in 2008.

“It had a bunch of janky roller coasters and spinning things,” Koekkoek recollected. “We loved it because it felt dangerous.”

For as long as he could remember, there were rumors about kids flying off roller coasters and getting killed at Thrill-Ville, but he couldn’t find evidence of any fatalities. He became obsessed with accident reports from Disneyland and other major amusement parks. “Nobody ever dies in Disneyland — which doesn’t mean people don’t die there,” he explained — or alleged. “It just means they don’t declare them dead until they’ve moved their body off the grounds.”

The story is a compendium of amusement park horrors overseen by drugged-out carnies: “The previous season a heavy drunk managed to launch himself from the Magic Carpet Slide, then plummeted a floor and a half down to a concrete walkway. We didn’t think that was even possible, but then the guy came soaring overhead with his shirt off. Cracked his pelvis clean through. Messed his pants on impact, instantaneously.”

While Takacs was getting her PhD in creative writing at USC, Koekkoek would visit her. This resulted in the L.A. story “Dirtnap,” which anyone who has felt defeated by the city’s byzantine parking regulations will appreciate. While struggling to park his girlfriend’s roommate’s van, the protagonist accepts the aid of a passerby, who promptly drives off with the vehicle. The narrator makes the situation worse by lying about it, turning a clever plot element into an emotionally fraught moment — and a study in surprising consequences.

“I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness” is a novel torn from Watkins’ desert life — Charles Manson, addiction and the incessant pursuit of true freedom.

Koekkoek flirted with academia while living for a time in New Orleans and Virginia. But back in Portland, he has no plans to return to teaching. His path to publication was equally haphazard. While attending Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference as a waiter work-scholar — a program that was discontinued in 2019 — he attracted the attention of the agent Henry Dunow, who eventually took him on as a client.

After they developed the collection together and went out with it, Simon & Schuster editor Sean Manning was charmed by its stories of young men who find themselves in predicaments whose solution may be obvious to the reader but not to the protagonists.

“The overarching malaise that this collection gets at typifies contemporary America in the 2020s,” Manning said via telephone, “but no matter how grotesque or violent the situation these characters find themselves in, ultimately there’s a goodness that each one of them seems to possess.”

It’s true that Koekkoek’s stories are like a microcosm of our era: Old ways of understanding the world are pitilessly dismantled, challenging the characters to find new approaches to their problems — except none of it happens online. Was Manning leery of Koekkoek’s lack of engagement with social media?

“I thought that was really kind of refreshing,” Manning said. “The disparity between what one would expect a young writer to be — super online and overly self-promotional — and somebody who just doesn’t seem to be all that interested in that kind of thing.”

Cai Emmons discusses being diagnosed with ALS shortly after finishing the surrealist California novel “Unleashed,” one of two novels out this September.

After we completed the interview, Koekkoek checked the weather reports on his phone. The snow was piling up on his porch, burying my rental.

“I have a guest bedroom,” Koekkoek said ominously, “but if you want to get back to Seattle tonight, your window of opportunity is shrinking.”

I said my goodbyes, brushed the snow off my mini-SUV and cranked up the defroster. I barreled out of the bowl at the bottom of the street, passing cars that were sliding or stuck. For a while I followed a fool riding an electric scooter and I felt like a character in one of Koekkoek’s stories. When I finally made it to the relative safety of the highway, I thought of the end of his story “The Flight Instructor,” in which the narrator trudges through a blizzard on foot:

“The snow was up almost to my knees, and the icy top layer made it hell to get through, breaking through again and again each step. I felt it in my hip flexors and faintly in my conscience, because like anyone else, I always feel sad to ruin fresh snow.”

Ruland’s new novel, “Make It Stop,” will be published next month by Rare Bird Lit.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.