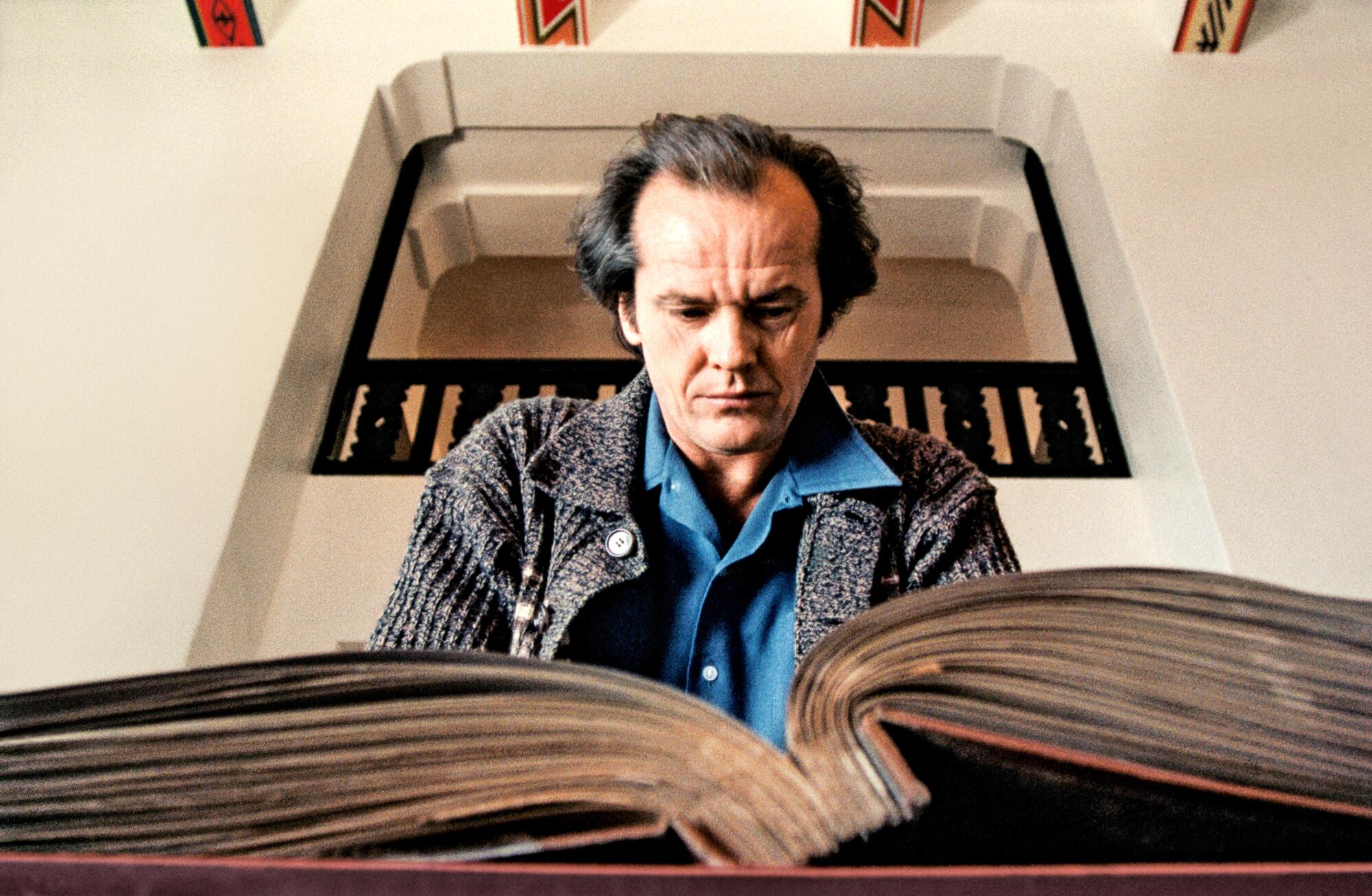

I can’t drive, so when I went to Oregon in 2016 I had to convince friends that borrowing a car to ascend Mt. Hood and see the Timberline Lodge would be “fun.” If the name’s unfamiliar, the hotel probably isn’t: The Timberline is the model for the facade of the Overlook in Stanley Kubrick’s horror classic “The Shining.” It’s where Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) takes a job as winter caretaker, accompanied by his wife (Shelley Duvall) and psychically gifted son (Danny Lloyd), and where, under the malevolent influence of the hotel, he tries to ax-murder his family. For me, if not for my friends, it was an exciting day.

Warner Bros. / Kathleen Dolan)

I’m not alone in my mania. Legion are the admirers of “The Shining,” bewitched by its mysteries, all of which seem to encourage obsessive attention. Rodney Ascher and Tim Kirk’s “Room 237” (2012) offered a glimpse into some of the more outré fan theories: Did Kubrick fake the moon landings? (No.) Is the film surreptitiously about the genocide of Native Americans? (Actually… maybe a bit.)

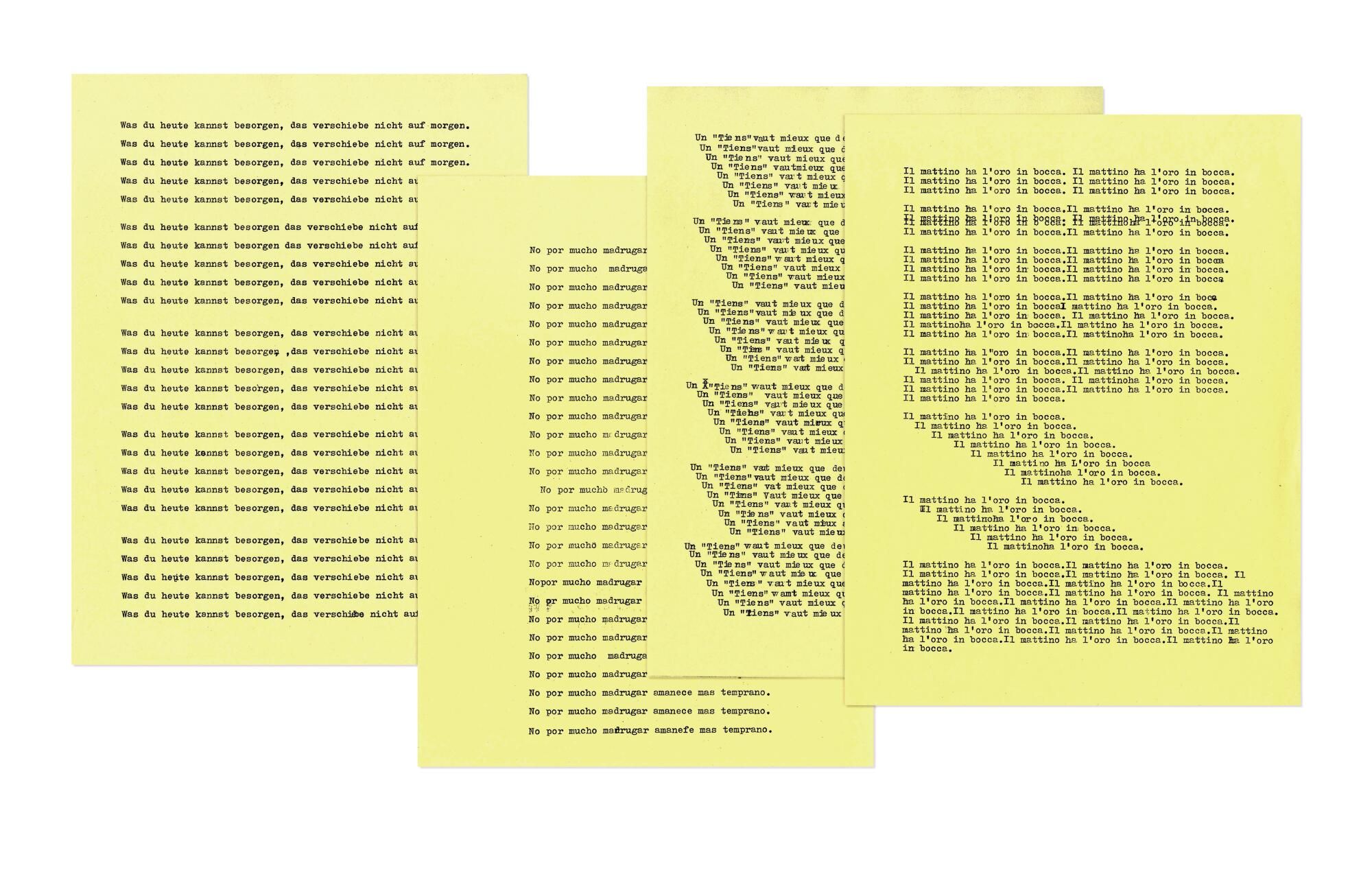

I recently spoke to someone whose love for “The Shining” leaves mine in the foothills. Lee Unkrich, the Oscar-winning director of “Toy Story 3” and “Coco,” has been called “the world’s foremost ‘Shining’ aficionado.” He is the “caretaker” of a long-running Tumblr devoted to the film and now the author of “Stanley Kubrick’s ‘The Shining,’” the ultimate completists’ guide to the film’s lore and visual ephemera. Written with J.W. Rinzler, it draws on extensive interviews and archival research and is being released by Taschen as part of a lavish box set, with a 900-page “making of” as its centerpiece. (The collector’s edition of this behemoth sells for $1,500 a pop, but based on the success of Taschen’s other Kubrick books, it seems safe to predict a more affordable trade edition one day soon.)

Shining a light on metaphorical readings of ‘The Shining’

Crammed with unseen materials and photographs — Unkrich estimates that 75% of the featured images, excluding film stills, will be new even to serious enthusiasts — this collector’s dream sets a new high bar for Kubrick fetishism. Unkrich and I chatted ahead of a March 17 screening of “The Shining” at the Academy Museum which will officially launch the box set, his enthusiasm undimmed even after a decade-plus writing the book and more than 40 years since he first checked in at the Overlook.

“I first saw ‘The Shining’ when I was 12 years old,” Unkrich says. “I grew up with my mom taking me to see a lot of films that were probably too old for me.”

For the imaginative only child of a “difficult marriage,” the film struck a personal chord. He soon acquired the Stephen King book on which it’s based and an obsession was born. But it wasn’t just that he identified with the material. Kubrick, he suggests, designed “The Shining” to obsess. “There’s an anecdote in the book that I love where Stanley has just finished a shot and he turns to a crew member and winks and says, ‘Let the French film critics figure that one out.’”

When Leon Vitali was working on Stanley Kubrick’s “Full Metal Jacket,” he became involved in a disagreement with the director over the size of cabins in the shoot.

Kubrick is notorious for his perfectionism — “The Shining” holds the Guinness World Record for “most retakes for one scene with dialogue” — and the book is filled with tales of devotion (or submission) to his obsessive vision. “There are times you put Stanley first and you’re second,” says focus puller Douglas Milsome, whose hand once froze to the camera lens during filming. When one of the sets burned down late in production, Danny Lloyd worried they’d be there for years while it was rebuilt. Even after the movie wrapped, Kubrick’s personal assistant, Leon Vitali, traveled to Malta, where Duvall was filming “Popeye,” to record some “wild track” for the snowball sequence — only for Kubrick to decide he didn’t need it.

But it’s Kubrick’s relationship with Duvall that receives the most attention today. His daughter Vivian captured footage of them arguing in her 1980 documentary about “The Shining,” and more recent talk of cruel behavior has cast a shadow over the film. But based on his interviews with people who were there, Unkrich says such rumors have been “exponentially exaggerated steadily over the years.” Kubrick was perfectly happy for his clashes to appear in Vivian’s documentary, he points out.

“It was right at the end of production, and everyone was crispy,” Unkrich says. “Were there things done that maybe would not be OK, by today’s standards? Yeah, probably. It was the late 1970s.” (As recently as 2021, Duvall said Kubrick had been “very warm and friendly” to her.)

Stanley Kubrick loved classical music.

Preconceptions about Kubrick are challenged by other revelations in the book. “People put Stanley up on a pedestal as this brilliant filmmaker, which he of course was,” Unkrich told me, “but they also imagine that every last thing was worked out ahead of time, and that he just then flawlessly executed these films. And that’s not what happened.”

As in Michael Benson’s terrific “Space Odyssey,” about the making of “2001,” and Matthew Modine’s “Full Metal Jacket Diary,” readers will learn that Kubrick started shooting without a clear sense of how the film would end. “He didn’t even know he was going to have [psychic chef Dick] Hallorann killed until much later in production,” Unkrich reveals. “ I think that these stories … are emblematic and illustrative of something that really pierces the myth of Stanley Kubrick.”

The process of writing the book was also long and occasionally rocky. Rinzler and Unkrich initially made two separate proposals to Kubrick’s estate, but once introduced they quickly discovered they were “kindred spirits.” Immersion in the Kubrick archive gave Unkrich a sense of the breadth of what they’d find, though it took many years to track down the dozens of people interviewed for the book, including Duvall, who hadn’t acted since 2002, and Lloyd, by then a teacher in Kentucky.

It was Unkrich’s relationship with Lloyd and his parents that led to the “mother lode” that sets the book apart from previous “Shining” analyses. Their family album, and hundreds of negatives from their basement, gave the writers a cache of material they’d never dreamed of (“my jaw hit the floor,” recalls Unkrich). Other discoveries in the Kubrick archive included negatives from scenes later cut from the movie, such as a hospital-set epilogue briefly seen in early screenings but hand-excised from every print before the film was released nationwide. These images are just some of the book’s major contributions to Kubrick studies.

The 12 years of the book’s gestation have not been without sadness. Rinzler passed away in 2021. (“He will always be the Caretaker,” Unkrich writes fondly in the acknowledgments.) Vitali, whose devotion to Kubrick was captured in the documentary “Filmworker,” died last summer. “He’d been carrying the mantle of Stanley’s wishes for so long,” Unkrich recalls.

Kubrick died in 1999. Given his legendary attention to detail, it seems likely he’d have approved the methods that produced this new “Shining” history. And while this private man may have been less keen on such a guts-out examination of his process, he could surely have had no concerns regarding the sanctity of the film’s mysteries. Despite all the revelations, for fans of “The Shining,” it will never fully yield its secrets.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.