How MIT scientists fought for gender equality — and won

On the Shelf

The Exceptions: Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science

By Kate Zernike

Scribner: 432 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In 1999, MIT made the shocking admission that the university had discriminated against its women scientists … and promised to do better. The 16 women who had challenged the status quo, most notably Nancy Hopkins, the reluctant de facto leader, were thrilled but eager to return to their roles as elite scientists.

They largely moved on. So did the Boston Globe reporter who broke the story, Kate Zernike, trading her higher education beat for a national correspondent role at the New York Times. But nearly two decades later, the #MeToo movement compelled her to revisit the moment for a new book, “The Exceptions: Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science.”

“In 2018, I was thinking, it’s great that people now think that executives cannot take off their bathrobes in front of junior employees, but it struck me that the bias and sexual discrimination the women at MIT had pointed out actually remained a much more pervasive problem,” Zernike said recently on video while on a family vacation in Utah.

Covering politics, she has repeatedly seen men’s success attributed to “genius” while women get grudging credit for “grinding away.”

“We do not take women as seriously intellectually or professionally, so this story underscores that point and serves as a reminder of the way we look at people.”

The issue became personal once Zernike had children. While male colleagues plastered cubicles with their kids’ art, she didn’t because she didn’t want to be seen as a mom first. It didn’t help. Men at the paper would toss off comments like “I was told you couldn’t travel” or “I just figured you wouldn’t want that job anyway.”

Women-only science programs at hundreds of colleges nationwide are coming under attack as sex discrimination against men

“People make fun of workplace training we have to do but unconscious bias is real and so subtle,” she says. “Talking to women in different fields, I realized we’re not quite as far along as I’d hoped. It struck me that Nancy’s story could be instructive to people.”

In intimate detail, Zernike narrates Hopkins’ entire journey — from uncertain undergraduate in 1963 to determined postdoc to innovative cancer researcher and admired professor. “It was really important to Nancy that I show her passion for science and show her doing science,” Zernike says. “She stumbled into this role as women’s advocate. It was not something she sought out.”

Still, it’s the obstacles that drive the narrative — an esteemed scientist grabbing her breasts, male colleagues trying to appropriate her work, lower pay, less grant money and less lab space for her and other women. Hopkins secretly measured every room in the building where she worked to prove her male superiors were lying about the space imbalance.

Working alone or with men had made it easy to ignore systemic problems, and still easier for the scientist to blame herself. “It’s humiliating so you don’t tell anyone,” Hopkins said during a phone interview. “It was only when women came together and saw the pattern that it changed.”

Zernike builds her case with the stories of other women, including cytogeneticist and Nobel Prize winner Barbara McClintock, geneticist Mary-Lou Pardue, nanotechnologist Mildred Dresselhaus, social psychologist Lotte Bailyn and oceanographer Penny Chisholm.

Hopkins says she was initially reluctant when Zernike reached out again; she didn’t want to relive the fight. She had already attempted and abandoned a memoir. “But the other women in our group wanted this story told in fuller form,” Hopkins said. “It was painful to go back — I was naive and clueless — but reading it I can now understand my own life. You see the historical context.”

The saying “You can’t fight City Hall” captures the immovable nature of government bureaucracy.

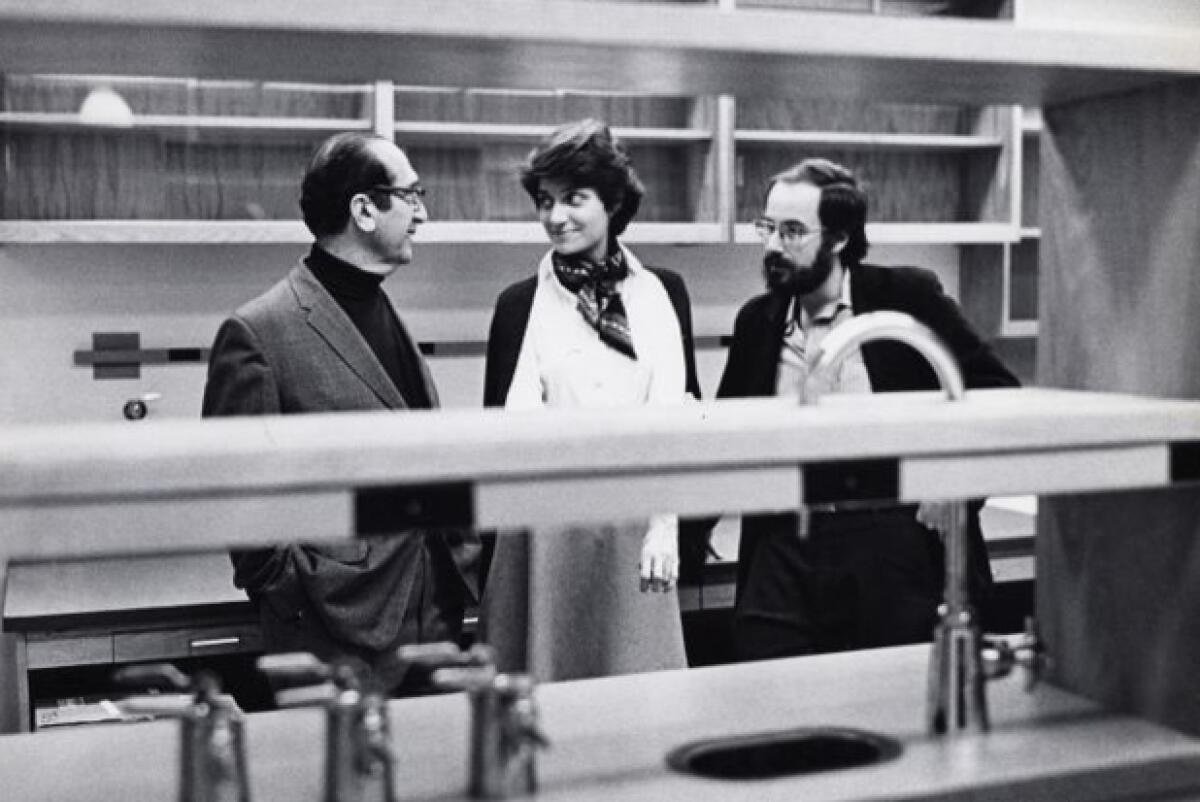

(Perhaps as a sign of how pervasive those biases are, only seven of the book’s photos are just of women; five are portraits of men or have a man as the focal point. “I was not conscious of doing that,” Zernike says.)

For decades, each woman scientist’s presence was considered by men to be an exception, underscoring the sense that women were not equal even though they had to work harder, sacrifice more and battle against endless slights.

“When the MIT report came out there was this right-wing backlash, saying it was just these women complaining. So I wanted the book to be a close-up experience of what it feels like to be marginalized,” Zernike says. “You don’t want to object every time because you look like a whiner. But it’s the accumulation of them that makes things so hard.”

Hopkins insisted Zernike interview the men involved and give their version proper space. The response was mixed. The most prominent scientist, Eric Lander, was unrepentant. (Lander was recently forced to resign from President Biden’s cabinet due to accusations of bullying.) By contrast, Harvey Lodish, his partner in shoving Hopkins aside from a course she created, had done some personal reckoning.

“He’s said, ‘You should write this book, just please don’t discourage women from going into science,’” Zernike says. “He can recognize in the greater context how this might have seemed to her.”

Years after the MIT apology, Lodish actually partnered with Hopkins to try bringing more women into the biotech field. When Zernike asked what changed for him, he responded, “We all grew up.”

Attending the 50th anniversary of Ms. last week, I thought I would find anger and regret. Instead I found memories of an anti-toxic office culture.

Looking back, Zernike and Hopkins both give mixed grades on what’s improved since 1999. “The mistake every generation makes,” Zernike cautions, “is thinking that the progress they see is the end and therefore we don’t need to keep talking about this.”

Hopkins agrees, which is why she sees value in a book recounting the events decades later. “If you don’t keep working at it, things will not only stall, they may go backwards.”

Both women point to less than encouraging statistics — higher attrition rates for women, who still represent less than 25% of the workforce in science and engineering.

Yet they celebrate MIT’s transformation: The university’s president, head of research, chancellor, provost and dean of science are all women, as are five out of eight department heads in the school of engineering. Hopkins, who insisted on a Black co-chair when named to lead a diversity council after the 1999 report, emphasizes that this list includes a Black woman, an Asian American and immigrants from Turkey and Pakistan — women for whom the obstacles “have been doubled.”

Just as crucially, the culture is finally changing. While Hopkins and many of her generation forewent having children, she notes that women today show up for job interviews pregnant, take family leave and still get tenure. And, per Zernike, the lionization of the “lone genius” in science, often used as a cover for bullying, is gradually giving way to a spirit of collaboration. “As we see more women in leadership roles, we will see that model shift more,” Zernike says.

When asked if men are educable on this front, Zernike laughs and points out that “my sons by osmosis learned that women can be geniuses.” While she was writing “The Exceptions,” Zernike showed her boys “Good Will Hunting,” set at MIT. In the famous scene in which Will (Matt Damon) takes a break from his janitorial duties to solve a nearly impossible math problem, Zernike says her 13-year-old burst out, “Wow, he’s Nancy smart.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.