How Richard Bausch learned to stop worrying and trust his instincts

On the Shelf

'Playhouse'

By Richard Bausch

Knopf: 352 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

If you were at a party with the Shakespeare Theater of Memphis, the fictional troupe at the center of Richard Bausch’s new novel, the atmosphere might not be much fun. Actor Malcolm Ruark would be quietly brooding over his fall from grace as a local news anchor, his co-star Claudette Bradley fretting about the deteriorating mental health of her father. Theater manager Thaddeus Deerforth would be worried about pretty much everything, from the massive construction project of a new theater to random bits of bad news around the world to the close partnership of his set designer wife and Reuben Frye, the much-loathed visiting director helming their upcoming production of “King Lear.”

But if you were lucky enough to be at a party with Bausch, the author of “Playhouse” and its “Lear”-sized cast of supporting players, you’d likely be far more entertained. Bausch, who has taught writing at Chapman University for a decade, is the award-winning author of nine collections of short stories and a dozen wide-ranging novels including “Violence,” “Peace” and “Good Evening Mr. and Mrs. America, and All the Ships at Sea.”

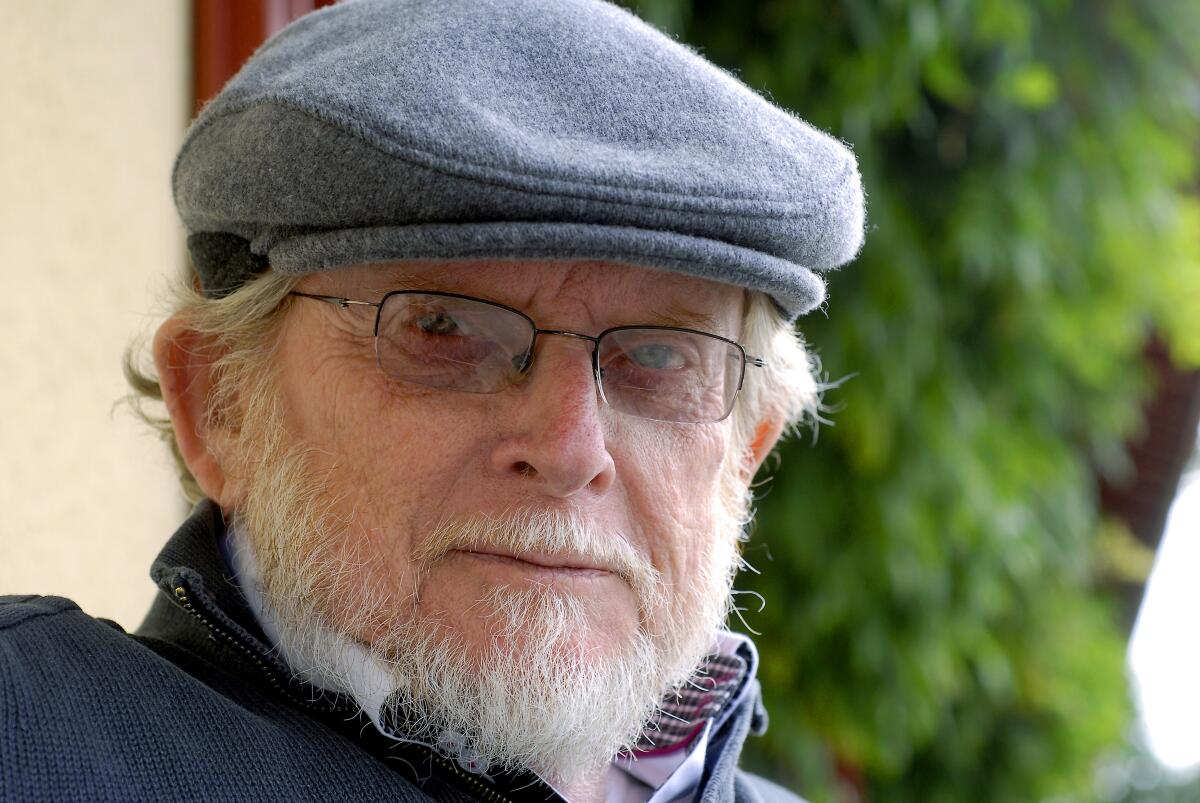

For our video interview from his home in Orange, Bausch — who in decades past has done some acting, stand-up comedy and guitar playing in a rock band — wore a jaunty flat cap and sat close to the camera. Behind him was the standard author’s wall of books, but you got the feeling that if the camera could pan the room, there’d be a party filled with laughter and bon mots, maybe even painful shared confidences and small epiphanies.

Authors including Hector Tobar, Marie Lu, Jervey Tervalon, Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo and Matthew Specktor consider what makes an L.A. or O.C. writer.

The guests might be a mix of ghosts and the living, writers whose names flowed continually through our conversation — late twin brother and fellow novelist Robert, of course; James Dickey (drinking too much); Eudora Welty and Elizabeth Spencer; Allan Gurganus; and Bausch’s wife, Lisa Cupolo — who, he proudly notes, just published her first collection of stories, “Have Mercy on Us.” (In the novel, Frye appears a pompous ass for name-dropping Al Pacino and Edward Albee, but Bausch’s references feel well earned.)

More directly crucial to the novel at hand would be his colleagues at Chapman. For research, Bausch picked the brains of John Benitz and especially Tom Bradac, who built and ran Shakespeare Orange County, both directing and starring in “King Lear” along the way. Another staff member inspired the novel’s Lurleen, the generous and efficient woman who oversees all the details of the office while raising two grandchildren.

Our talk felt less like an interview than an especially revelatory string of cocktail chatter, as Bausch’s musing replies meandered into entertaining anecdotes only peripherally connected to the original query.

While “King Lear” is, Bausch notes, the novel’s MacGuffin, the vehicle for exploring the toil and trouble of his own cast, it is a play that inspires great passion in the author. He was already a Shakespeare fanboy when he first read it in the Air Force at 22. It became his favorite play, a frequent reread.

“I’ve seen almost every version, including one in 2004 with a deaf and mute Cordelia like the way Frye wants to do it,” Bausch says, adding that he enjoyed that production and knew he’d use it in a story one day. “I also saw an awful one, where Lear comes out on a giant throne 10 feet above everybody, making him just ridiculous. I go back to Paul Scofield, who was just amazing as Lear, where he makes the speech, ‘I would not be mad …’ and really gives you a man praying to keep his sanity. It was so moving.”

“All’s Well,” Mona Awad’s delightfully odd but strangely noncommittal new novel, concerns a woman who overcomes her ailments in Shakespearean ways.

Bausch relates to Lear. “When I was 28, I became afraid for my sanity,” he says; into his 30s, he felt like a “judge and jury convened in my head over any thought that wasn’t exactly proper.”

He credits Welty with transforming him in one simple sentence. “We were drinking whiskey with crushed ice in big goblets at a party — everyone else was drinking wine or beer — and talking about stories, and she said, ‘Just to be alive is to have crazy thoughts.’ That washed over me like a revelation, and I thought, ‘Why have I been so worried about this stuff?’”

Nonetheless, anxiety and darkness remain constant companions for Bausch. What the writer likes to call “spiritual arthritis” informs the internal strife of his characters, especially Malcolm, Claudette, Thaddeus and his wife, Gina.

Thaddeus’ constant anxiety is becoming irksome for Gina, although depression settles over her as well. Malcolm had been a drunk (and drug user) overly attentive to his underage niece Mona before a crash and DUI ended his TV career. Finally given a second chance, he’s trying to rouse himself from his torpor and return to his acting roots — an effort complicated when Frye (perhaps sensing a PR angle) casts Mona as Cordelia. Claudette has some demons in her own past. This is one “Lear,” in other words, with a lot of baggage.

The feeling that infuses the story — the sense that catastrophe awaits at every step — has plagued Bausch since childhood, he says, perhaps because when he was 2, he saw a girl get hit by a car in front of his house. The idea of perpetual danger was confirmed years later when his sister and her husband, parents of four, were killed in a car crash. “No matter what is going on, my brain presents me with the possible bad outcome,” he says.

When I asked if this was why many of his characters feel unsafe in the world, he replies, “It’s just the way they come to life. I’m never quite conscious of what’s going on. It’s more …” and then he veers off into a typically insightful digression:

“Flannery O’Connor once said a good story is literal in the same sense a child’s drawing is literal. I remembered an experiment I’d read about in Time magazine in 1967, where young kids were asked about their home life and made these amazing drawings. There’s dad with an ass the size of Missouri looking into the refrigerator, which is full of cans of beer, and Mommy is this big [he holds up fingers to indicate something tiny] next to a Matterhorn of laundry with a sad look on her face. The kid isn’t saying, ‘I’m using symbolism,’ it’s just what the kid sees. For me, trying to write is trying not to think too much and to regain the direct gaze of a child. In revisions, you add subtleties that underpin what you set down in that half-conscious state.”

He’s interviewed Neko Case, Jeff Tweedy and Maria Bamford about depression. With his new memoir, “The Hilarious World of Depression,” John Moe looks inward.

That state initially produced a funny but overly long book. The humorous bits “made people laugh their asses off when I read them at parties, but there were so many places where the story seemed to pause to do the schtick that I took most of that out,” he says.

Bausch’s revision process is rigorous, but he also long ago learned to trust his instincts, something he honed through his teaching. He recalls working on “The Man Who Knew Belle Starr” back in the 1980s. The ending was growing twisted and violent, and Bausch was doubting himself. “I thought, ‘What the hell is this? I’ve been watching too much damn television.’”

But that day he met with a student who was worrying about where his character was going; Bausch caught himself encouraging the student to follow the story where it went. “A voice in my head then said, ‘Why don’t you follow your own advice?’ And I went home and finished the story overnight.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.